The Interview

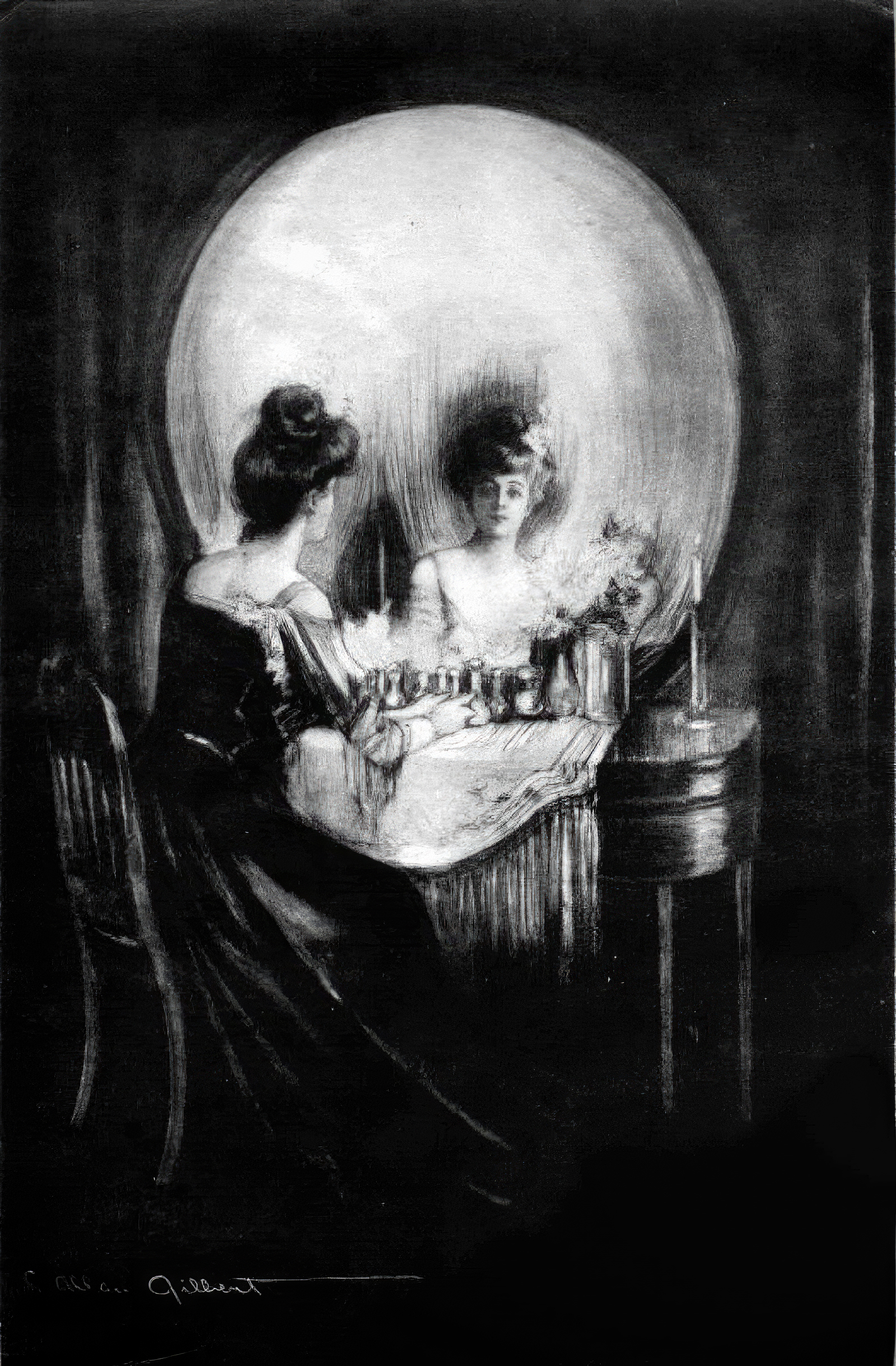

All is Vanity – Charles Allan Gilbert

Marisol Tublé was 107 years old, and so it felt like something of an affront to wake up in a strange and extravagant hotel room with a headache and no recollection of how she had come to be there. Headaches were the ailment of the young and lazy, Marisol thought, for people who drank too much or did not want to listen to tiresome piano-playing relatives. At 107 one ought to have graduated to more noble illnesses.

She lay in the bed, her wrist against her forehead, staring up through the semi-gloom at a ceiling of painted panels and trying to recall what she had to do to today. There had been such a lot of traveling the past few weeks. She remembered that much. She was a singer—the Great Warbler Marisol—and she was on a tour. Her final tour. A sudden throb passed through her head and she had a brief impression of concerts, one after the next, the hustle and bustle behind stage, the murmur of the audience as they settled into their cradle of anticipation, the flare of the stage lights, the swell of the orchestra, and the swell of her heart the beat before she began to sing, Budapest, Rome, Darmstadt. . . But where was she today?

She rolled over and squinted at the silver clock on the nightstand. She couldn’t see its numbers. It was a blurry, ticking moon, too far away. She dragged herself closer and stared at its blank face. Her old, old eyes flickered over the spiny hands. Then she let out a small squeak and sat straight up, her frail frame like a pole in the dark.

Nine o’ clock. It was nine o’ clock in the morning, and faint, butter-colored light was slipping through the slit in the drapes, and she could hear the distant calls of birds and people. Marisol remembered: she had been on the final leg of her tour, almost done, and then there had been some unpleasant incidents, and she had been invited to visit one of those small, dusty countries that no one really knows exists, and to perform a concert there, as well as a brief conference to speak to the local press. That was it. She was staying at a hotel on the Rue de Marmiet, and her contact, a man named Mr. Devereux was to pick her up at 9 thirty from the lobby to take her to her interviews. Which left her with only thirty minutes to prepare herself and take her breakfast.

Ah well. The stage waits for no man. Or was it ‘Death waits for no man?’ There was no great difference.

She began to struggle out from among the sheets, heavy, scratchy, frilled things that smelled of must and rose-petals. She kicked them all onto the floor, slid off the bed, hurried for her dressing gown. . . .

It was odd that she had forgotten where she was. She could remember things from her childhood, clear as a glass of water, could remember stumbling on a curb on a hot summer day and losing an ice-cream cone to the muck of a gutter. She could remember her mother, playing piano, teaching Marisol to sing. But she could not remember where her performances were one day to the next. She frowned and began taking the curlers from her hair and rowing them up on the top of her vanity.

She felt very tired still, and the headache hadn’t left her. She hoped the interviews would go quickly and that the journalists would be pleasant. She began shuffling through the contents of an alligator-skin cosmetics case, bottles of tincture and clasps of powder clinking together softly beneath her fingers. She brought out an elaborate perfume-diffuser and poof’d a cloud of violet-smelling mist onto her neck. One time, twice, again and again. Yes, she hoped very much the journalists were pleasant.

* * *

It took Marisol about twenty minutes to prepare herself, and that was in a great rush, without the attention to detail she usually gave herself. She painted her paper-thin skin very carefully, white as porcelain, with lead and bone-powder. She dabbed her lips and rouged her cheeks. She put on strings of pearls and a small hat, and when she was all finished she raised her head and smiled at herself in the mirror. Her face was a thousand hatches and cross-hatches, and she had not so much crow’s feet around her eyes, as octopus feet. But when she smiled, even in the silence and of the dim hotel room, her face turned glowing. Her eyes flashed, piercing and charming and witty and warm all at once, and had anyone been watching at that moment, her gaze would have struck home like a bolt of lightning.

The look faded as quickly as it had come. Marisol’s eyes dulled a little. She began puttering about.

Interviews. Interviews, and then a concert. And then she was almost done.

She adjusted her hat put on a pair of gloves, and then she let herself out of the room and went downstairs to the breakfast room. It was already 9 thirty by then, but it was not good to be early to anything, especially when meeting people one didn’t know.

Marisol had four bites of toast and three cups of black coffee in the breakfast room. It was a very shabby breakfast room. And empty. It might have been grand once, but it was difficult to tell because it was so dim, and there were great, many-ruffled drapes over the windows. The only person in the room was an attendant standing by the buffet, still as a statue. Marisol watched him as she nibbled at her bread, and drank the last of her coffee. Then she set down her napkin and hobbled out of the room. She found Mr. Deveraux waiting for her in the lobby.

“Mr. Deveraux,” she said, coming up to him and smiling again, that brilliant, flashing smile. “I hope all the preparations have been made in my dressing room for this evening?”

Marisol always asked that there be a bottle of Mr. Thymus’s Throat Soothing Syrup, as well as six pink roses and a piece of chocolate waiting for her after every concert. She didn’t really like chocolate, or pink roses for that matter, but if she didn’t ask anything people tended to get lazy.

Mr. Deveraux looked at her curiously when she spoke. Then he nodded and gestured for her to follow. He was a small man, and he seemed rather nervous. Marisol thought that was just as well. Nervous people were much easier to handle than confident people. He did look vaguely familiar, though. She watched him as she followed him through the glass doors and into the street. Perhaps it was just another old memory, a snippet of someone long dead. Perhaps it was not even that.

Mr. Deveraux escorted her along the street, through the sticky morning air. It was not a hot day, but it was one of those uncomfortable mornings where the heat was just enough to make one scratchy and sweaty simply by existing. The street was deserted. Quite as empty as the hotel’s breakfast room had been. It was lined with shops, shuttered and closed, a city hall, a cathedral and several cafes. Marisol could not hear the birds anymore, or the call of the people. It was utterly silent here.

Mr. Deveraux led her into the shadows of a promenade, past a beetle-black automobile and some dying palm trees, down a stretch of cobbles, waiting every few steps for Marisol to catch up.

Marisol didn’t hurry. She never hurried anywhere, not anymore. She looked around her with great interest, and whenever Mr. Deveraux looked at her with those questioning eyes of his, she smiled at him and continued to feign enjoyment of the scenery. They arrived, at last, at a tall, terracotta-colored building, and Marisol followed Mr. Deveraux up a flight of steep steps, ever-so-slowly, down a short hallway, and into a room furnished with two hard wooden chairs, a table, a vase of dead flowers, and nothing else.

Marisol frowned. This was a sad country indeed if this the best they could do. Why had the journalists not simply met her in the hotel? But again, ah well. One must be understanding of other people’s customs. Marisol stepped into the room and sat down on one of the chairs.

“I suppose we’d better get on with it then,” she said, and breathed deeply as though steeling herself for a great trial. “Please show them in one at a time, Mr. Deveraux.” Then she smiled one more time at him, and said began fanning herself with a small feathery fan.

“Y- yes,” said Mr. Deveraux, and peered at her again, and darted out. What an odd man, Marisol thought, turning her attention to a small window in the wall. It could be that Mr. Deveraux never seen an opera star before. Or perhaps her make-up was slipping. The heat was just enough to do that. She began quickly touching about her eyes and hair, and then the door opened and she dropped her hands into her lap.

Mr. Deveraux poked his head in. “Erm- ” he said.

“Yes?” said Marisol. She was beginning to feel somewhat annoyed. It was not a good day to be sitting in an ugly, stuffy room. She needed to begin practicing her scales. And why was everything so empty and desolate here? She still could not hear the sounds of a town through the window, and the birds were silent, too.

“Yes, erm . . . The journalist is here.”

Marisol clicked her tongue. “Yes, show them in. Quickly, please. I’d like to get back to the hotel as soon as I possibly can.”

Mr. Deveraux nodded, but he did not leave. He adjusted his collar. Finally he said: “There is only one to see you today, Marisol.”

Marisol paused her fanning, eying him. “Only one journalist?”

Mr. Deveraux nodded.

Marisol stared. That couldn’t be. Was there only one newspaper in this country? Granted, she was not in her prime any more, but that there should be so few interested in the Viennese Nightingale, the Star of Copenhagen, the Great Warbler? That was very nearly insulting.

“Yes, yes, all right,” she said, a bit testily. “Who needs a lot of journalists anyway? The sooner we’re finished the better. Show him in.”

Mr. Deveraux ducked his head and hurried out of the room. A few seconds later he returned, bringing with him a man. Or at least, something vaguely human-shaped.

The man who came in was not very much like a man at all really, or even much like a journalist, and the sight of him made Marisol flinch in her chair so hard that it creaked.

The man-thing was very stooped. He had a great, warty mushroom going out of the side of his head, his eyes were rheumy, and his skin was sagging in all the wrong places, so that it looked like a wet bag draped across his skull. His coat was covered in moss and barnacles, rooted in deep blue cloth. He came in, clumping over the floor, and settled himself heavily opposite her.

Marisol leaned forward, squinting. “You- you are the journalist?” she asked quizzically, and then looked to Mr. Deveraux. But Mr. Deveraux had already fled.

The man-thing watched her for several seconds, his eyes blunt and heavy. Marisol watched him back. She paid careful attention to the mushroom growing from his face, which seemed to be changing colors slowly from russet to deep-green.

“Please ask me questions, then,” Marisol said. “I haven’t got all day. If you’re the only one here, I’d like to be finished very soon. How long do you think you will need?”

Here the man-thing cleared his throat wetly and said, “I will ask the questions,” and took out an old pad of paper and a lead and began scribbling away at it. Marisol gasped. I will ask the questions? Did he mean that simply as a preamble to his question-asking, or was he telling her that he would be the only one asking questions, and therefore would not answer hers?

In which case he was being very rude. “I beg your pardon?” she said angrily, and hammered one heel on the floor.

“You have a concert tonight, then?” asked the man-thing, ignoring her question. “You are going to sing for a great audience?”

The man-thing spoke very quickly and only looked at her briefly, and all the while he scribbled in a notepad in his hands, though Marisol had not yet answered with a single word.

Marisol stared at him, her hands clasped tight in her lap. What in all earth? “Mr.- Mr. whoever you are, I am a singer, and you are a reporter, and it is your business to ask me questions that are not stupid. Proceed.”

The man-thing looked up at her quickly, then down. “Are you a good singer? Have you been singing a long time? Perhaps as a job?”

Oh, thought Marisol. She knew what game he was playing. It was one she had come across many times before. The envious, faintly aggressive sort, who made a point of being ignorant of everything his subject had ever done, in order to make his subject feel small and insignificant. Well, Marisol was beyond that. She had met all the varieties of writers and journalists in her interviews throughout the years—sorts who smiled very wide and then wrote articles all of black slashes and bits of hate, sorts who were cold and aloof, sorts who were callow and eager, and asked far too many questions, so that she had to flap them away like flies. This was just another kind, this envious creature. Perhaps the man-thing was a singer, too, and was deemed too ugly for the stage. There was the saying that if you could not do, you taught. Equally true might be: if you could not live, you wrote.

“You are clearly new at this job,” said Marisol sharply, at which the man-thing looked up with some irritation. “I suggest you research journalism and proper etiquette and how to remove fungi from your face, and then perhaps we can speak again after my concert this evening.” She stood, swaying a little on her feet.

“What do you remember about yesterday?” asked the man-thing, not moving at all.

Marisol ignored him, making her way slowly toward the door.

“Fine then, what do you remember from last week? Were you happy last week? Or were you sad. Perhaps you were sad. A bit depressed, even.”

What a perfectly foolish question for a newspaper article. But then newspapers weren’t what they used to be. People didn’t want information. They wanted stories. Exciting stories. Tragic stories. Funny stories. False stories.

Marisol reached the door and tried to open it. It wouldn’t budge. It was locked. She wheeled around on the man-thing, who still hunched over his pad, back toward her, scribbling.

“Do you like it here?” he went on. “Or would you rather be somewhere else?”

Marisol was trembling now, part with rage and part with fear. How dare he? Why had she even come? What was this wretched city and its wretched hotel? “It is ghastly here,” she spat, not even thinking. “You are ghastly. The hotel is ghastly. I hate it. I hate all of it. I am leaving the moment my concert is done, and you can be sure I will have nothing pleasant to say of you when I am home again. Now, I demand you let me out.”

The man-thing did not move a muscle. Scritch-scratch-scratch went the nib of his pen, and the ink splattered.

“Mr. Deveraux!” screeched Marisol, and it almost killed her to do it because screeching was not good for the vocal chords. “Mr. Deveraux?”

The man-thing didn’t look up. “What time is your concert tonight?”

“I am not a signpost! Go and find a flyer and look it up.” Marisol began pounding against the wood, her thin hands cracking painfully on the frame.

“What are you singing?”

“The Arias from Tosca!” she screamed. “From Puccini! Let me out!”

“Do you know what happens in that opera, Mrs. Marisol? In Tosca?”

“Of course I know! I’ve sung the role a thousand times! Do you know?”

“I do. I do know. It is about a great and desperate lady, who at the end of Act 2, takes a knife and- Marisol, it’s about a person who murders another person, and then runs away.”

Marisol stopped pounding the door. She turned on the man-thing, and the man-thing turned, too, in his chair and looked at her with his mournful eyes and hideous face. Marisol’s gaze was very sharp just then, and so lucid, that even the man-thing stared. And then Marisol smiled. Her last resort. Her final tactic with reticent journalists. It was a desperate, terrible smile.

“It’s all very sad, isn’t it. But the music. The music!”

The man-thing closed his pad. “Marisol,” he said gently, and he no longer seemed so dreadful. “Marisol, I am not a journalist. I am doctor. Do you remember? Do you remember anything?” Suddenly he looked rather sad, or perhaps pitying.

Marisol continued to stare at him, her smile fixed, her powdered skin cracking into tiny filigree beneath her eyes.

The man rose from his chair. He didn’t look quite so strange anymore, not even to Marisol. He didn’t even have mushroom growing out of his face. And his coat was the blue of a uniform, wasn’t it. No moss or barnacles. A blue uniform with a red cross above the heart.

“You’re lost, Marisol. It has been forty years since you were last on stage. It’s been forty years since you were anywhere but here, since you took up that knife and- ”

“It’s wonderful, isn’t it,” she said, pointedly ignoring that statement. “Everyone knowing you. You know, I always thought you’d really made it when you don’t have to tell people things about you anymore and they just know.”

“Do you have any memories of your family? Who they were? Perhaps if you remembered that, we could trace someone, find someone to- ”

“There is no one,” said Marisol, and the smile dropped from her face like a stone. “There is no one left. People die. They forget. But the audience doesn’t. I’ll always have them. The audience loves me.” Her words were ferocious there, wild and sharp . . . and then her face softened again, and she looked simply tired and frail and rather annoyed, waiting to leave so that she could go and warm up her voice.

* * *

Mr. Deveraux came back to collect her after the doctor had gone. “How was the interview?” he asked, helping her from her chair.

“Odious,” said Marisol. “The journalist was a boor. I think he disliked me from the start. I don’t even want to know what the article will be like.” She began to warm up her voice even as she walked, her notes high and reedy, like a cracked whistle. She broke off a second later and began fanning herself vehemently. “He was clearly just a bitter pudding. That’s what my mother would say. A bitter, bitter pudding, all nasty and rancid. You know, I’m glad there aren’t any more reporters in this wretched town. I don’t think I could bear to speak with them. I will sing for the audience, yes, but then I’m done. I’m flying straight back to Paris. Mr. Deveraux, you may arrange the car to pick me up first thing in the morning.”

Mr. Deveraux nodded patiently.

And as they walked down the street and into the hotel, the world seemed to drift around them, disintegrating. The floral wallpaper faded to white plaster, the chandeliers wilted into iron lamps, and the drapes fell to nothing over bare and glaring windows, barred on the outside. Marisol was no longer dressed in velvet and pearls. She limped along in thin slippers over the green floor. Her clothing was a white shift. But as Mr. Deveraux brought her back to her cell on the third floor of the Belvoir Institute and guided her gently through the door, she turned and smiled at him, and there were those eyes again, diamond-bright, and her face enough to light a stage, and it made Mr. Deveraux pause for a second in awe.

“I’m ready to sing for them,” said Marisol, and her eyes flashed one more time. Then she vanished into her cell, and Mr. Deveraux closed the door behind her and locked it.

As he went away down the corridor he heard the sound of music drifting after him, the beginning notes from one of Puccini’s arias, rising, rising in a small, broken arpeggio, and for an instant he thought he heard the rustling of an audience, the breath of excitement as the stage-lights flared and the curtain began to rise. . . .

The Knot Inside

There’s a string in the back of my throat. At least that’s what it feels like.

Like there’s something thin and rough, coiled there, waiting.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to swallow my food.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to breathe.

It must be growing.

I think, soon, I may have to try and pull it out.

Whatever it is.

*

I’ve tried to trace the arrival of the string back to an event in my life, and this is the best I could come up with:

The string, I think, must have arrived on Francis’s first day of school.

Francis Eckhart is this girl who moved here from Wisconsin. One of the Midwest states, anyway. She’s got an accent. She has great clothes. She makes decent grades without even trying.

She has beautiful hair.

Out of everything, that’s what I noticed most.

I have terrible hair. It’s this fine, mousy brown mess, and I can’t get it to look anything like it’s supposed to.

The first time I saw Francis, it was in the cafeteria at lunch. She didn’t have anywhere to sit, so I did this dorky wave at her, and she came over and sat down across from me.

She smiled at me and my friends, and we all started talking about Wisconsin and moving in the middle of the school year and how awful that is. Also, movies. And Stephen Parker, who flirts with the lunch lady because he thinks someday she’ll give him an extra piece of pizza for free. She never does.

So we talked. It was nice. It was normal. It was whatever.

But the whole time I couldn’t stop thinking about Francis’s hair. It’s long and golden. Rapunzel hair. Smooth, shiny.

I had this fantasy, in that moment, at the lunch table, about taking a knife and cutting it all off, really close to her scalp, and sewing it onto my own head.

It wouldn’t hurt her or anything. Come on. I’m not violent.

But it was kind of a violent thought, and that surprised me. I’m not violent, I swear.

The thought seemed to come out of nowhere.

It’s just that I have really impossible, mousy brown, very non-Rapunzel hair. Which doesn’t seem very fair. Like, cosmically.

I kept thinking about that all day. How exactly would one sew a head of someone else’s hair onto one’s own scalp?

Hair transfer!

No idea.

But thinking about it got me through an especially boring afternoon of world geography, science labs, and algebra.

I mean, whatever you’ve got to think about to tolerate the school day, right? It’s not like I would actually do that to Francis.

I wish that I could. But I never would.

*

So I got home that night, and that’s when I felt the string.

At first I thought it was just a scratchy throat. Okay, fine. Drink some water, suck on some cough drops, have chicken noodle soup for dinner.

Freak Dad out, just a little. Just for fun. Just for a little bit of pity.

No, Dad. Seriously, it’s okay. (God. So much for fun.) I don’t need to go to the doctor. It’s not strep throat. It’s not the flu. It’s just a cold.

But it wasn’t a cold.

It was the string.

I realize that now.

*

After that, I started to notice things I never paid much attention to before.

Like, for example, I have a decent number of friends, right? I’ve known some of them since I was really little. We pass notes in class, we have sleepovers, all that.

I’d never been unhappy with that before.

But then, maybe a few days after I first felt the string, I noticed how Stephen—he who flirts with lunch ladies—didn’t just flirt with lunch ladies.

He sort of flirted with everyone.

It wasn’t like he liked everyone. Not like that. It’s just he’s the kind of kid who makes friends like other people take breaths.

I started observing him as much as I could without seeming like a freak.

He had this way about him, this way of saying all the right things at all the right times. This way of making jokes that were just the right amount of corny.

I could never be like that.

I always say all the wrong things at the wrong times. My jokes are either too corny or I don’t tell them right and they fall flat as wet paper.

I started imagining that Stephen had this secret component inside him, like a part to a machine, that gave him the ability to do these things. To make friends like it was nothing.

I am an awkward person, there’s no doubt about that.

Stephen is the antithesis of awkward. It’s kind of revolting.

So, this secret component of Stephen’s, this machine part. What if it was something I could extract? What if it was something I could carve out of him like when we carved out the livers of those rats last year in science?

What if I could install it in myself, and become like him, but better? Like him, but me?

I thought this one day, drifting along with everyone down the hall, from lunch to algebra to world geography to gym.

I found myself examining Stephen from afar. Not like I was checking him out or anything like that. Puh-lease.

But more like a doctor might. More like a doctor might look at a person and try to figure out where a disease might have originated, so he could proceed to cut it out.

*

And so it went, on and on.

I kept experiencing these thoughts, these daydreams, that felt . . . wrong. They felt somehow . . . not mine. They came out of nowhere—slicing off Francis’s hair, carving out Stephen’s anti-awkward flirt device.

Stealing Garrett White’s money. (He got such a huge weekly allowance, and for what? For having the luck to be born into a rich family? Give me a break.)

Somehow absorbing Luis Mendoza’s IQ. (Maybe another exercise in carving? But how to get through the skull to the brain without damaging its parts?)

Raiding Donna Beach’s house, stealing her collection of trophies, awards, medals, ribbons. Scratching off her names and replacing them with my own. Scratch, scratch, scratch. With a nail, or a knife. (And you better not come running at me, Donna. You better just let me steal them. I have a nail. I have a knife.)

*

It was that last set of thoughts that made me do it.

That last set of thoughts scared me. I could almost feel the knife in my hands. I could almost see Donna Beach’s terrified blue eyes.

Swipe.

These thoughts, they came out of nowhere.

They came out of a dark nowhere deep inside me. A nowhere that wasn’t mine. At least, it didn’t feel like mine.

So I lay curled up on the bed for a while, my hands clamped over my ears, my eyes squeezed shut, and I cried and whimpered and tried to will the images away.

Like when you’re lying in bed at night and think you hear a movement, see a shadow, feel a breath in your hair, and you know it’s just silly, it’s just your imagination, it’s just your half-awake mind playing tricks.

You can, if you do it just right, convince yourself of that—that nothing’s there, you felt nothing, you heard and saw nothing—and you can fall right back asleep.

So that’s what I lay there trying to do.

But I couldn’t.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t keep from thinking these thoughts of knives and cut hair and carved body parts and sweaty money that should have been mine, friends that should have been mine, a body—a beautiful, skinny, blond-haired body—that should have been mine, mine, mine.

No matter how hard I tried, still the thoughts scratched.

Scratch, like a nail across wood.

Scratch, like a blade across a shiny gold medal.

*

So I get up.

There’s a string in the back of my throat.

It must be growing.

I think, although I don’t understand how, that these deep, dark nowhere thoughts have something to do with this thing tangled up at the back of my throat.

So I get up.

I go into the bathroom.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to breathe.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to stop these thoughts from bursting out of me into action.

There’s a string in the back of my throat.

I think, soon, I may have to try and pull it out.

So I get up.

I go into the bathroom, and I lock myself in.

I go into the bathroom, and I lock myself in, and I climb up onto the bathroom sink.

And right there, beneath the glaring lights—four, in a row, gold-rimmed, movie star style! It’s time for my close-up! Dressing room glamour! And I think of that movie star, that actress, and I think of how her perfect megawatt smile would look on my face, and I think of what her long skinny legs would look like on my body, and I think about what it would take to make those things happen.

And right there, beneath the glaring lights, I open my mouth wide, reach back into my mouth with my fingers, find it—Yes! I was right! A string, coarse and thin and coiled!

And I pull.

*

I pull, and I pull.

I pull the string, and it keeps coming, like one of those magic tricks where the guy has colored scarves hidden up his sleeve, only this isn’t funny.

It’s snaking, it’s sliding, it’s snagging its way up my throat, across my tongue, between my teeth.

I stumble off the sink and onto the rug. I am kneeling now, and still pulling.

I keep gagging because it feels like I’m pulling out my own insides.

I want to throw up, but more than that I want this string out.

Something’s on the end of this string. On the other end, deep inside me. I can feel the weight of it tugging.

So I pull, and I pull.

And finally, the rest of it comes loose, a tangle of dark coarse string on the floor.

I sit there. I am gasping, trying to breathe. My throat is sore from the pulling.

You okay in there, sweetie?

Yes, Dad. I’m fine. I just pulled ten feet of string out of my body and it’s sitting on the floor in front of me like a dead thing and I am A-OK.

Then, the string begins to move.

It begins to take a shape.

At first it kind of weaves around like a charmed snake, and it knots and un-knots itself, and it smells like my blood. Like waking up from a nosebleed, in a mess of bloody pillows. Like getting hit in the face with a soccer ball and having blood spurt down your face and down your throat until you’re literally drinking it.

That is what this smells like.

I watch it happen. I should run, maybe, but I seem to have forgotten how to move my legs.

Then the string isn’t a string anymore.

It’s taken the shape of a person, all the details outlined with the string that was inside me, and the insides are blurry, like dirty fluid.

It’s an odd construction, but I still recognize it.

The string has taken the shape of me.

*

“Well?” says the string-me. The ghost-me. The echo-me.

It’s me, I know that somehow. Like, if you saw one of your own pulled teeth in a line-up of other people’s pulled teeth, maybe you’d recognize it. Like that.

It’s me.

But it’s a better me.

This me has long, golden hair. Shiny. Smooth. Rapunzel hair.

This me has a look on her face like she knows just what I want, more than even I do, and she’ll let me have it if I ask nicely.

This me has good skin, clothes that aren’t hand-me-downs, clothes that fit right. This me reeks of money.

This me has an intelligence in her eyes that I can’t look directly at, like the sun.

This me has a dozen gold medals around her neck.

This me has long, skinny legs and a megawatt smile.

This me is all my deep, dark nowhere thoughts come to life. This me is . . . everything.

“Well?” She says it again. She looks me up and down, crosses her arms. “Are you ready?”

“For . . . what?”

“For me to change your life.”

I lick my lips. “How?” But somehow I already know.

She stares at me for a while. Flicks her golden hair over her shoulder. I watch it cascade, and I swear to God there’s a part of me that actually hurts to see something so beautiful—on me.

“I know all the things you’ve been thinking,” she says. She kind of sings it.

I blush. “That’s impossible. You’re not—”

“Real?” She laughs. God, to have a laugh like that! Mine is this really unfortunate bray. And yet . . . and yet, in that perfect laugh of hers, I can hear, faintly, the sound of my own laugh.

My own laugh, but better.

“I promise you I’m real,” she says. “I’m real because you made me real.”

“How did I do that?”

She pauses, tilts her head. Her eyes flash. “By wanting.”

The word drags out of her mouth like the string had dragged out of mine.

“Wanting . . . what?” I say.

But she just stares at me.

“Wanting . . .” I pause, swallow. My throat is so raw it’s like swallowing gravel.

“Wanting to be like you,” I say. “Wanting to be beautiful. To be smart.”

“To have trophies and medals,” she hisses, taking my hand. “To have money and long, long legs.”

“To be . . .”

“More.”

“To want . . .”

“More.”

She says the word over and over. She combs my hair with her fingers, and already my hopeless lank droopy hair feels more beautiful. She runs her fingers across my scalp, and already my brain feels sharper, more focused.

It feels good.

It feels fantastic.

I want more of this.

“More,” I whisper to her.

And then I take her hand.

And it’s at this moment, when her cold, scratchy hand folds around mine—when I feel that familiar coarseness of the string that was in my throat and now forms the outline of her cold, scratchy, made-of-thorns hand—that I see her close enough to understand.

I see how her scalp bleeds in a patchwork, where she has threaded these long blond locks into her skin.

I see how her perfect, glowing skin bears stitches—her fingers, sewn into place here. Her long, long legs, attached with thick black thread there.

I see how her eyes sit in her face funny. I see the tiny stitchings around the sockets.

I see how the medals around her neck are made not of gold, but of skin—stretched tight, gold paint lazily slapped on top.

I hear how her words aren’t words, but thousands of tiny buzzing sounds, held together in the shape of words by this mouth full of teeth that have been stitched into her gaping gums.

This close, I no longer see myself in this creature.

I see what she truly is.

She is my deep, dark nowhere thoughts.

She brought them to me, she is them, and I helped her out, into the world, into my bathroom, holding my hand, stroking my hair.

She whispers of the great, terrible things we will do together.

How I will never want again.

This close, I understand what I have done. What I will do.

I try to pull away.

But it’s too late.

She is unlocking the door.

Her hand is around mine.

She has me.

Chicken; Egg

See a city street!

See a yellow summer evening, oh see. See it in a city. A lovely, perfect heat: unless you are a man in a black wool suit, watching the flickering rectangle in your hand, as your shiny black shoes clip-clip against the concrete as sharp and quick as hooves.

See the man! He sweats in the heat, brooding of clients and contracts. Striding, striding, watching as words flicker in his hand.

See him look up.

Hear the sharp clip-clip of his shoes go silent.

Across the yellow evening he sees a woman, a strange woman (strange to him!). Strange, her dark blue dress, the darkest blue of a near-night sky. Strange the white patterns swirling across the skirt!

(But are the patterns strange, or are they so familiar? Think, sweating man!)

See her! Bright white hair stands out around her head. Daubs of color streak her face like shooting stars, white and midnight blue. Her feet are bare and dirty. Around the woman flow the city’s evening walkers, like river-water around a rock. Yet no one seems to see her but the man.

She does not see him. Up and down the street she looks, and bites her lip, as if she has lost her way. (A TRICK!)

Ah now, now! See what the man sees! See what the woman holds, in both hands, pressed tight against her belly, but showing just a little, just a little: just to be sure he sees.

It is an egg! A golden egg. A glittering golden egg, swirled with patterns of tiny jewels, sapphire and diamond, like the patterns on her skirt (oh think, sweating man! you know those patterns!).

Oh the man sees the egg! He sees it and sees it. His eyes blink twice, three times, four. The man is rich, or almost rich. But an egg like that, that is the riches of the moon and sun.

Now! The woman looks upon him, startled, her eyes shocked wide. (A TRICK! A clever trick!) One hand lifts her midnight-blue skirts; she turns.

She runs.

The man gives chase! (She meant him to!) His phone goes skipping across the cement, his abandoned briefcase offers paper to the winds. The man swings into an alley; sees blue skirts flip around a corner; follows.

He follows and follows! When he cannot see her, he listens for the swish of skirts. He chases her down narrow streets and broad ones, dodging cars and hot dog stands, calling Wait, wait, I only want to see the egg.

At first, he calls. But soon, he stops. Does he stop because he is out of breath? Does he stop because she does not respond? Or—oh worst thought of all the worst—does he stop calling because to see it is no longer all he wants?

Still: see how the woman leads him, as the sky darkens the city, how she waits when he tires, how she flies when he nears. To the alien edges of the city she leads him, over unfamiliar pavements in decaying districts, running lightly on her dirty bare feet.

Through narrower alleys, past wooden-board lean-tos, past rusting automobiles. . . .

The woman stops! She stops, she stands still, in a lightless, deserted street. Beside her sits a low box made of wires and rotten boards. They have arrived!

The man and the woman stand, panting. The sky is dark as the woman’s skirt.

And now it is darker!

And now, oh lovely now, in the dark sky, the tiny lights begin, so delicate at first! The beginning of a symphony, the whisper of lovely strings. The tiny lights come: one, two, three, six, eleven, more and more, winking like the jewels on the golden egg, and to my ear—I mean, to the woman’s ear—each jewel-light blinks on with a soft, pure voice, until the constellations are great choirs of harmony and counterpoint!

Are they stars, those tiny lights? Or are they bright fish, swimming in and out of constellations, singing their star-fish song?

Watching the tiny, swimming lights, the man’s face is open as a bell. He says, The sky, but the sky—is this what it always is?

With joy, such joy, the woman kneels! (Does he see, as her skirt billows out, that her dress is a pattern of milky galaxies and stars? He does, he must!) She kneels by the rough box and pulls a board aside. Inside, in the dark, the man can just see—what? What do you think? What do you guess?

The most wonderful thing: a chicken! Inside the box is a white chicken with a red comb, rather dirty, like the woman’s dirty feet, and seated on a dirty straw nest.

The woman slips her egg beneath the chicken. Then, with great care, she lifts them all—nest, chicken, egg—and stands. She smiles now, at last the woman smiles at him! At last she can give him the glorious gift she has led him here to find!

I say—I mean, she says—oh, well, it is me—did you guess it was me? I am the woman! It has been me all along, telling this story!

I say: My dear, my dear boy, I have a gift for you, a glorious gift, all you’ve ever asked for and all your dearest heart desires.

With full heart, I offer him the chicken.

But oh, the worst happens!

For somehow, during the long and merry chase (it was merry! I thought it was merry), something has happened.

He began the chase with, Let me see it, let me see your egg. As I wished him to feel! So that he would follow me here!

But somehow, in the course of the chase that feeling became, My egg. It is my egg. Give me my egg.

So when I hand him the chicken, joyfully—oh the beautiful, dirty, clucking, odd-smelling chicken—he strikes it! He pushes it away! It falls, the chicken, it flaps wildly to the cement, squawking—and it hurries away.

Oh lost, the chicken lost!

And oh no, oh worst of all, oh ruin—the man seizes the egg in his hand!

NO! I cry, oh no, oh no! as I feel myself yanked into the night sky, as if pulled by a string from the stars: No! I cry, oh no, he didn’t mean it!

But it is too late. And for him, my cries fade fast. For him, soon, I am only another tiny silver fish in the dark, constellated sky.

From the sky, I watch through tears, as he looks at the egg, at that little golden planetarium and its jewel-constellations.

I watch through tears as the egg splinters in his hand—as it must! As all such eggs must splinter when grasped by human hand!

The golden egg shivers to dust at his feet. All that is left in his hand is what was once inside the egg: a tiny white chicken, curled in a ball, wet with egg juice.

Inside the egg, it was alive and growing. Now it is quite, quite dead. And dead is the tiny golden egg inside that tiny chicken; and the tinier white chicken inside that tinier egg, dead too; and the even tinier egg inside that tinier chicken—all dead, all dead, countless chickens, countless golden eggs, dead, dead, dead.

And yet the stars sing on around me!

For the rest of this man’s life, I will watch him from the sky, as he struggles and fights and wars the world to earn another golden egg. I will watch him battle, watch piles of green paper grow taller around him, watch the other black wool suits shake his hand.

But he will never be happy. I work so hard, I work so hard, he will think, all the rest of his life. Where is my egg?

From the night sky, I, the man’s own star-fish, I will weep, as I do tonight. What will it matter, how hard he works, when he works for the wrong thing? What does it matter how hard he works for the egg, when only the chicken would have made him happy? Only the chicken, the beautiful, odd-smelling, squawking chicken, that he was freely given by a star who came with dirty feet to answer his heart’s desire, his own swimming star-fish, who can never come again.

China

This story begins the way most things begin, which is to say that this story begins in a rather dull way: a milkmaid is getting ready to take her tea. She is a very poor milkmaid, and her cottage is bare as an egg. It has a three-legged iron stove in one corner, and a rug that’s gone threadbare and grey in the spot where the milkmaid stands to churn the butter. There are cobwebs in some places, and dust in others, and in one corner there is a photograph of two smiling people who are perhaps the milkmaid’s parents, but they are dead now. The only thing of any interest in the cottage is a set of china tea-things, sitting atop the sideboard like a veritable shrine.

It is a splendid tea-set, though upon closer inspection one can see that the china is a lacework of cracks, and very old. There are two dainty cups with tiny orange flowers painted around the edges, a creamer and a sugar-bowl with a pair of pewter tongs to fish out the lumps. There is the loveliest, loveliest teapot you can possibly imagine. And on the bottom of three of the pieces are symbols, sharp black lines and crosses, a language the milkmaid has never been able to read.

The milkmaid drinks tea from her tea-set exactly once per week, and she takes great care to make the occasion special. She sweeps the floor with a twig broom, opens all the windows to exchange the air, boils the water, measures out the precious leaves, arranges her tea-things precisely, sits down at her table. . . .

*

Should you have come by the milkmaid’s dwelling just then and peered through her bottle-glass window, the scene that would meet your eyes would most likely strike you as ridiculous—a stout milkmaid, no longer quite young, alone at a wobbly table, trying to be prim, simpering with the sugar bowl, buttering slips of bread and nibbling at them prettily. You would think her silly.

But the milkmaid does not know that you are watching, and so she doesn’t mind. She is very happy when she drinks from her tea-set. It was her inheritance from the smiling people in the photograph, and when she uses it, when she even looks at it, she feels she is a child again. She feels her parents are right there with her, and she feels they will always be her parents as long as she has the tea-set. It is her favorite thing in the whole world.

Until one day. Until today.

*

For just in the moment when the milkmaid is lifting the teacup to her lips, the teacup moves. Only a little bit. Only one tiny, tiny shiver, like a bird about to hatch. But it moves.

The milkmaid looks at it quizzically. Then she raises her eyebrows and brings the cup back to her lips. The cup shivers again, this time so severely that flecks of tea spatter the milkmaid’s nose. The milkmaid, in an attempt to calm the teacup, lays it back hastily on its saucer. But it does not stop. It continues to shiver, rattling and spilling tea over the rim, harder and harder, and now suddenly there is a voice, cold and pure as porcelain, saying: “Break it. Break it. Split its back and shatter its bones.”

The milkmaid jerks away in terror, but the teacup continues to speak, hollow and dark, louder and louder. And then the milkmaid picks up the cup in a fright and throws it down with all her might against the tabletop. The teacup explodes into a dozen small white pieces . . . And what should come out of it but a very long, skinny creature, brown and red and green, and flat as paper. It might be a dragon, but it is very furry, and it has horns. It turns a circle on the tabletop, joints clicking, looking rather stiff, and then, noticing the milkmaid’s wide-eyed stare, squints up at her and says in a silky, hissing voice:

One wish now

Quick and careful

Then have your tea

And be quite cheerful.

The milkmaid screams and hits the creature with a heavy fist, and its legs squeeze out on either side. But then it turns to smoke and blows out from under her fingers, and comes to rest on the corner of the table.

“Come now, quickly, what would you like?” it says, in a slightly less sinister voice. The milkmaid screams again.

The creature peers at the milkmaid askance. “I do not understand your wish,” it says.

The milkmaid lets out one last strangled cry and then puts her head between her knees, trying to calm herself. She has heard tales like this one. Be careful what you wish for. Be careful, be careful. She raises her head. The creature is still there. She watches it carefully, and it watches her back.

“Shouldn’t you give me three?” the milkmaid squeaks. “Three wishes?”

“One wish!” says the creature imperiously. “And you can’t wish for more wishes, now hurry.”

The milkmaid thinks and thinks, so long that the creature wonders if perhaps it got a bad apple and it will have to wait all night. The milkmaid thinks of the tales she has heard, and she tries to makes sure her wishes will not backfire too badly, and then she says: “I would like a great lovely house, furnished and weather-tight, right here where this house is.”

And the next instant the cottage is gone and it is replaced by the strangest, most marvelous building the milkmaid has ever seen. The walls are lacquered wood, and the floors are strewn with pillows, and the windows are large and wide. The rooms are a bit too colorful for the milkmaid’s tastes, and she is not enamored with the artwork, but it is too late to change anything, because the creature has dissolved into a purple plume that is making its way up the chimney.

*

The milkmaid is so pleased with her new house. She wanders through it and admires the many rooms and the many windows and fire-pits. She finds the remaining pieces of her tea things sitting on a low, glimmering table, and her heart hurts for a moment, for the broken teacup, but then she thinks the china looks even more lovely now, like it belongs here. She thinks she will be very happy now.

But the next day, a tax-collector, coming along the road down from the town, sees the great mansion and he comes up the path and knocks at the door, wondering where this wonderful new house has come from and whether it has been properly taxed. Of course, it hasn’t. The milkmaid is very afraid when she opens the door. She tells the tax-collector that the house is only just built, and she will be paying the taxes the very next day, and then she closes the door quickly and locks it, and hurries through the house wringing her hands and wondering what to do. She doesn’t want to sell the house, or anything in it, and she doesn’t have time to, really. She comes to stand in front of the magnificent tea-set, sitting on its table. She stares at it. And now she is taking another teacup, and her heart is pounding so dreadfully. She is lifting it and smashing it on the floor. She winces as it breaks. Please, she thinks. Please be another strange, small creature.

And indeed out slips another one, this one like a spider, emerald-green, with long and spiny legs. It says:

In such a house

All red and gold,

What could there still be

You wish to hold?

And the milkmaid says, “Quickly, please, I must pay all the taxes on my house and I haven’t any money! Give me all the money I will ever need.”

The next instant the house is full to bursting with gold and jewels. There is enough to pay all the taxes for the rest of the milkmaid’s life, and she nearly dies of relief.

*

It is not long after the tax-collector had come and gone, that people begin to notice the beautiful house with its many gables and colored walls, and begin to think the milkmaid far more interesting than they had before. They come from far and wide to knock on the milkmaid’s door and speak with her, and she revels in the attention. No one ever visited her before. No one spoke to her, except to tell her the cows were in the wrong field, or the milk was late. Now they compliment her lovely house and the gape over all her gold and jewels. But as time passes, the milkmaid notices that while they talk to her a great deal they never really say anything. It is so strange; the milkmaid is sure she had had better conversations with the tea-set in her lonely cottage than with these people, who paw over her furniture and drink great quantities of her tea.

The milkmaid doesn’t know why this is. She wonders long and hard, and she decides it is because she is still a great clumsy milkmaid, and though she is kind and unassuming, she feels she is not as fine as all the wonderful people who visit her. Perhaps, she thinks, if she were like them, they would be her friends. They would tell her secrets and invite her to their own homes, and not just come to hers. And so, without another thought, she goes to her tea-things and takes up the sugar bowl and smashes it on the floor, and out comes another odd creature, this one like a black worm, all glistening and wet.

A third wish then?

Again, again?

You want a lot,

You silly hen.

The milkmaid says, “I would like to be someone else. Someone beautiful. Someone more beautiful than anyone in the entire country, in the entire world!”

And the next instant she is just that, and the worm has split into a thousand smaller worms that wriggle and creep into the floorboards.

The milkmaid goes to the mirror. She can hardly breathe when she sees herself. She has glimmering crow-black hair, and her face is so beautiful it is like the sun and the moon and all the stars put together, and her old, work hardened hands have become long and fine as any china.

*

But when the milkmaid again receives visitors to her mansion on the hill, they are somewhat quieter around her, somewhat more cautious, and then one of them asks her what has become of the silly, ugly milkmaid who had lived here before. It breaks the milkmaid’s heart to hear them. She sends them all away. She stops letting anyone in when they knock. She becomes lonely, lonelier than she ever had been before, and though she tries to sweep her great house and lay out the tea-things and feel happy again, she has only the teapot now and the creamer, and it feels desolate somehow, and not the same.

At last, she is so unhappy that she goes to her teapot and clutches it to her. She does not want to break it. But then she thinks of the picture in the frame that had vanished with her old cottage, of the smiling faces, and she thinks of drinking tea and buttering scones in the quiet of her shabby home, with only her own thoughts and memories, and all her tea-things gathered around her, and suddenly she knows what she wants, she knows exactly.

She lifts the china teapot to her chest, after a long, fond gaze, lets it slip from her hands. There is a great crashing. The china blooms across the floor like a sharp flower. . . . But there is nothing inside the walls of the teapot. No dragon or spider or worm, and nothing to grant the milkmaid’s last, most desperate wish.

*

Now, if you came upon the milkmaid’s mansion and pressed your face to a crystalline window, and glimpsed through the gap in the velvet curtains, the scene you would meet your eyes would be very different from before: a beautiful room, and a beautiful woman kneeling in the midst of it, crying her eyes out, and spread all around her the remains of a lovely china tea-set, smashed all to bits. And perhaps you would wonder what such a beautiful woman could have to cry about, and you would see her gold and jewels and think she really has no reason to cry; she could simply buy a new tea-set. And you would go on your way, and think how foolish are the rich and vain. But the milkmaid would not know your thoughts, and she would weep and weep and weep. . . .

*

So as you see, this story ends differently than most things end, which is with a sunset, or a wedding, or a bloodied axe. But it is an ending, and the milkmaid has come to realize something very cruel about the world: that you can have a great many things from life, but not for nothing, and perhaps the things you gave away are what you wanted most.

Harvest Day

“Peter? Are you awake?”

“What do you think?”

“Sorry, jeez. Just . . . I can’t sleep.”

“No kidding?”

“I just wanted to talk. Okay? I’m about to go crazy over here.”

“Yeah, well, I don’t feel like talking.”

“Why are you being such a jerk? Peter? Pete, answer me. Are you still there? They haven’t—”

“No. I’m still here. And don’t cry, Adam. Just . . . don’t cry, okay? I can’t take it.”

“So?”

“So I’m just freaked out, all right? And I don’t want to talk about it.”

“Do you think They’ll take me?”

“You’ve asked me this a million times.”

“And?”

“My answer’s the same: I don’t know. No one ever knows who They’re going to take.”

“. . . Peter?”

“Yeah.”

“Are you scared?”

“You’ve asked me this before.”

“I know. I’m running out of thoughts. They’re all turning panicky.”

“Yeah. I don’t know. I’m scared, yeah. But at the same time, I’m so used to being scared about this night that I’m kind of past being scared. I mean, it happens every year, and there’s nothing I can do about it, so why waste time being scared about it? Does that make sense?”

“No. Kind of, I guess.”

“Yeah. Well, that’s how I feel. Until I figure out a way to get out of here, I’m stuck with this night, and I’m stuck with being scared.”

“Peter?”

“Yeah.”

“Do you think our parents knew about what goes on in this place when they moved here?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think so.”

“. . . Do you think they’d still have moved here if they did know?”

“What kind of question is that? God!”

“Well, it’s just that . . . it’s so beautiful here. You know? And my dad’s always wanted to live someplace beautiful. Maybe he thought it was worth the risk? I just wonder.”

“Let me tell you something: It isn’t worth it to wonder. You’ll drive yourself crazy. Have you heard the story about that kid Rory?”

“No.”

“Rory lived over on 10th Street. He was so paranoid when it came to his mom. Like, he thought she was in on the whole thing. That she’d made a deal with Them. Because he and his mom didn’t get along so well. You know? So he started to think she’d moved them out here so she could get rid of him, nice and clean, without anyone knowing, without her ever getting caught.”

“But, I mean . . . he was wrong, right?”

“Who knows? He tried to kill his mom one day. Tried to push her down the stairs. He just knew, you know? He knew she was in on it. He knew she was just waiting on the day They would come and take him.”

“God.”

“I know.”

“Well, so what happened to him?”

“He vanished after that. His mom was fine, though. She’s that old lady now, who lives on 10th.”

“Ms. Rowengartner?”

“Yep.”

“But she’s so . . . sweet.”

“Yeah. They all are, aren’t they? Until they’re not.”

*

“Peter! Pete, wake up.”

“Huh? What? Adam?”

“Listen—”

“I can’t believe I fell asleep.”

“Shut up! Just shut up and listen.”

“To what?”

“Outside.”

“Is that . . . ?”

“I think it’s next door.”

“Moira. Oh no. Don’t listen to it.”

“I can hear . . . what is that? Oh God, it’s Them.”

“I said, don’t listen! Plug your ears. Listening to Them is one of the ways They find you.”

“But Moira—”

“What are you gonna do? Save her? It’s too late.”

“Peter, I’m freaking out—”

“I’m right here.”

“They sound like—like animals . . .”

“It’s okay. Plug your ears. Just breathe. Breathe, and don’t listen, and They won’t be able to find you.”

“How do you know?”

“I’ve lived here all my life, and They haven’t taken me yet. So there’s that.”

*

“Peter?”

“Yeah.”

“Do you think it hurts? When They take you?”

“I don’t know. Probably.”

“I’ve heard people say that when they get inside you, it feels like your skin’s going to split open. I’ve heard stories about people taken by Them who go nuts before they’ve even been dragged out of their house. They go nuts and tear their own skin off because it hurts that bad.”

“I wouldn’t listen to stories, Adam. People will say anything.”

“You mean stories like the one you told me about Rory?”

“Yeah, well, some stories are true. You just have to know who to trust.”

“Who am I supposed to trust, Peter? Who am I supposed to trust when I can’t even trust my own parents?”

“You can trust me. I’m your friend.”

“For now.”

“What the heck, man? What do you mean by that?”

“I mean, what if it came down to a choice between saving me from Them and saving yourself? What would you do?”

“I don’t want to talk about this anymore.”

“Yeah. That’s what I thought.”

“I hope it was quick, for Moira.”

“You’re changing the subject.”

“Yeah, well, you’re being an idiot. I hate hypothetical questions.”

“. . . Do you think that was it, then? Are we safe now? Do you think what we heard was Them taking Moira?”

“Or was it a trick? Is that what you’re getting at?”

“A trick, or maybe Them just having fun. Not taking her, but just . . . messing with her.”

“I don’t know. You never know until the next day, at dawn, when you wake up and realize you’re still safe and in bed. That’s the only way you know for sure that you made it. That They didn’t take you this time.”

“Peter?”

“Yeah.”

“Is that the sun coming up, over there, do you think?”

“Could be.”

“Or maybe it could be Them burning someone’s house down, like last year. Flushing them outside.”

“Maybe. You never know.”

“Yeah. You’re right. You never know until dawn.”

*

“Peter? Crap! I fell asleep again.”

“Peter? Why is it so cold in here?”

“Peter. Peter, why did you open the window?”

“Peter. Come on, stop trying to scare me. Say something.”

“Peter, you know I’m not going to get out of my bed. My feet aren’t going to touch the freaking floor, not until sunrise.”

“Peter, I’m going to throw this shoe at you. I’m sorry if it hurts, okay? Don’t yell at me for it. I just . . . I have to know. And I’m not getting out of this bed.”

“Peter. God . . . Peter.”

“You’re not there. Are you? Pete?”

“You’re not there. Oh my God, Peter. I’m so sorry. I’m sorry I fell asleep!”

“They . . . I don’t believe it. I mean, I know I was asleep, but . . . They must have come in so quietly. I would’ve woken up.”

“Unless you went out on your own. Did you?”

“You wouldn’t be that stupid, would you, Peter? You wouldn’t try something stupid and heroic?”

“I would’ve woken up, if you’d yelled for me. I would’ve woken up. I would’ve helped you.”

“Peter. I’m so sorry.”

“I’m so, so sorry.”