March, 2014

Butterfly Blood

In the middle of a wide, snowy field, beneath a solitary tree, two nuns stood, side by side. Their black habits—blacker than the tree—flapped about their ankles. Their white wimples—whiter than the ground—framed their faces. Their sensible shoes, patent leather and pointy-toed, shone dully in the winter light.

The nuns did not move a muscle.

A man was approaching them from far across the barren field, tramping steadily through the frost and the silence. The man’s head was far too small. Or perhaps his body was simply too large. At any rate, he had a freakish look about him, like an ogre, and his skin had a pale, greenish tinge, a slimy-wet sheen.

The nuns regarded him as he approached, their expressions inscrutable. One of them, the smaller one, had her eyes opened very wide, but whether it was out of surprise or simply the permanent state of her face was impossible to say.

As the man approached, it became apparent that he had no fingers on either hand, only stumps, stopping at the first knuckles. When he ducked his tiny head, one could see he had no ears either, only holes on either side of his face.

The smaller nun didn’t say a word, but her eyes grew a fraction wider.

The man stopped several paces away, just outside the spreading reach of the tree. He bowed heavily and then straightened, shifting from foot to foot.

The nuns turned slowly and looked at each other. Then they looked back at the man, and the taller of the two held out a hand, as if to say, Have you got it? We have walked many miles. We have waited in the cold. Give it to us.

The man with the too-small head looked at the tall nun. Then he grinned gapingly, and the nuns gasped in unison because he had no tongue. No ears. No fingers. No tongue. Eyes, he had, but those are not nearly as useful as most assume.

He was the perfect messenger, of course. He could never tell on anyone, or whisper a tale, or scribble a note. That was why the nuns had called him. They should not have been surprised.

The taller one regained her composure and held out her hand again, more insistently this time.

The man nodded his tiny head, and his eyes lit up, and he slipped something from his sleeve.

It was not a bottle, or a packet, or anything like that. It was a butterfly, sapphire-winged and veined with black, and it emerged out of his sleeve and came to rest delicately on the end of one of his poor old stumps, flapping slowly, feelers curled against the wind.

The nuns looked at each other again. The smaller nun’s eyes were very nearly rolling down her cheeks. The man with the too-small head simply smiled at the butterfly in his palm, a look of wonder on his face.

Finally the tall nun nodded and inclined her head formally toward him. Then she put the butterfly in a small cage made of wire, and the two nuns went away across the field.

***

The man with the too-small-head watched them go, and watched the glimmer of the blue butterfly-wings in the cage.

When they were gone, he shook his head and grinned again, and he didn’t exactly disappear so much as simply move someplace else, someplace that was not the snowy field, but was perhaps just behind it, very close by.

***

The nuns arrived back to their nunnery very late. Before going inside, they made sure to pat some wet earth on the knees of their habits and clump a bit around the frosty heels of their sensible shoes, before finally letting themselves in through the great door.

They had herbs under their arms, but they had collected them the day before so as to have some time free to seek out the man with the too-small head.

They looked around stealthily as they entered the nunnery, stood still and nodded as other nuns passed by. The cage with the butterfly they kept hidden, clutched tightly behind their backs. When the Mother Superior saw them, she twinkled at them, her eyes very bright, and they both inclined their heads as she passed, but their faces remained like stone.

As the Mother Superior went on down the corridor, their eyes followed her, and the younger nun’s mouth may have twitched a bit—just a tiny, tiny bit—but in that flat, empty face it was like a bomb blowing up.

***

The nuns took the wire cage to their cell and sat a while, admiring the butterfly through the mesh. The nunnery was an austere place, busy and soft, full of shadows and whispers and echoing songs. The music was often rather sad and the colors were either dark or white, and so it was something of a marvel, this blue-winged butterfly in the gray cell.

The smaller nun, finally, looked at the taller one in a questioning way, as if to say, Do you think it will do the trick?

And the taller one looked back, eyebrows raised, as if to say, Who can know? They promised it would. Those wild things in the fields and moors, they promised, and I know they lie, but it should. It should do the trick.

Then she undid the latch of the cage with two long fingers. The butterfly crept out, blue wings flickering tentatively.

It was about to fly away, about to beat those wings once, twice, and flutter toward the ceiling. . . .

But the younger nun took a wooden mallet from the folds of her dress and smashed the butterfly onto the table top.

***

The nuns let the butterfly sit, squashed to the table, overnight, exactly as they had been instructed. Then they scraped the blue from its wings and the clear, watery blood from its veins, into a tiny thimble-sized bowl and set it out on the windowsill, in the cold, fresh air.

The smaller nun looked at the taller one, and her eyes said, I hope it works. We haven’t much time left. And what if someone starts to suspect?

And the taller one nodded in a way that meant, It will work.

The moon came out, half-full, like a sleepy eye, and squinted down at the bowl on the windowsill, and at the nuns, who looked away quickly and closed the casement.

In the bowl, the blue and the blood sat and drank in the moonlight, but also the night and the shadows and the cold, and the nuns went down to the evening mass and tried to forget about it until it was ready.

The Mother Superior was at mass, of course, and though her back was toward the two nuns, anyone raising her head from the hymn-book might have noticed the smaller nun staring at the Mother Superior, her eyes so wide and still. . . .

***

Five weeks earlier, the nuns had gone to the Mother Superior and asked her a question.

“Please,” the taller one had asked, and her voice was surprisingly soft and regular-sounding, papery and cool. “Might we have the third Saturday of next month off?”

The Mother Superior had twinkled at them. She said, “Of course you may have a day off! But not that Saturday. We’ll need you here for the weeding and the churning, and it’s baking day. You may have the fourth Saturday off. I will mark it down.”

You never would have guessed the nuns’ disappointment. They had looked at each other briefly, had nodded at the Mother Superior, and had slipped away without another word. But behind their placid faces, anger was roiling and tumbling like flames.

***

Here was the situation: a great violinist, Master Garibaldi, was on a tour across the continent. He was playing Bach, all the Chaconnes and Voluntairs, and the nuns pined to hear it, and pined to see him, too.

They could not tell the Mother Superior this. They were sure she wouldn’t understand how lovely Maestro Garibaldi was, and how his hair shook like a lion’s mane when he played his violin and how his music felt like a lamp, glowing behind your ribs. And so, when the tall nun and the short nun had been told they could not go to the City the day of the concert, they began to plot.

They read great grimoires in the library and went on long walks across the moors, and came upon the creatures of stone and moss in the wild hills, and all the while Maestro Garibaldi crept closer and closer across the continent toward the City, and the nuns worked more and more urgently, until at last they had it all, everything they needed for their plan, everything but the last bit, the most important bit.

There is a price to pay for all good things, one of the old, crusty books in the library told them. The highest price is not what one pays one’s self, but what one makes others pay for one’s own happiness. If you are willing to, you can have anything you like in life, only know that something beautiful must die.

The nuns had no compunctions about this and had gone to the man with the too-small head, and fetched the butterfly, and squashed it to the tabletop.

***

When the nuns were sure their mixture had ripened well on the windowsill and had turned into a good thick paste, silver-gray and speckled with flecks of shimmering blue, they brought it out into the early morning, to an open place where the wind blew strongly.

There, they set the bowl on the ground and the wind dipped into it at once, picked up its contents and blew it into the air. The flakes whirled a moment and then began to form a shape. A human-shape. A nun in a black habit—blacker than the stone walls of the nunnery. A white wimple—whiter than the nun’s teeth as they smiled and watched.

The wind swept over again, and the last of the mixture grew into the second nun, small and stout, with eyes like marbles.

The two sets of nuns stood looking at each other, one pair smiling, the other not. Then they nodded to each other and one pair set off into the nunnery and the other took off its sensible shoes and put on ones with bows and went to the City, where it heard the great Garibaldi playing on his violin and fairly well swooned.

***

That night, the wind came and reclaimed its breath from the delicate shell of butterfly blood and moonlight, and the false nuns fell to nothing. But by that time their namesakes where comfortably in their beds and fast asleep.

They weeded twice as many beds in the herb garden the next morning, those two nuns, and churned three times the butter, and perhaps, if one had watched them very closely, one might have seen them wink to each other over their work, their heads all full of music.

The butterflies of the area were less pleased, however, and there was an infestation the next year in the nunnery’s dining hall, small onyx-winged insects all up the rafters and under the edges of the plates. No one could understand why it happened, not even the two who had caused it.

Your Secrets for a Storm

Miranda had been taught by her mother, and her mother had been taught by her mother, and so on, back for a hundred generations in the kingdom of Aurestra, that little girls must never tell the wind their secrets.

Boys were all right; boys could shout at the wind until their throats bled, and the wind of Aurestra would pay them no notice. Boys pretend to be wild, but they’re not very much, not truly, not where it counts, and the wind only deigns to pay attention to creatures like itself.

Wild creatures.

Girls. Not women, but girls. Girls, because they have fire in their blood and storms in their eyes—the old fire, the ancient storms, of the time before cities. Before schools and science and libraries. Before the king’s palace was built. But girls must not show it, they must not unleash themselves, no—because girls are meant to be soft. They are meant to be sweet, and pretty like rose petals, and quiet, above all else. Quiet, quiet as sleeping birds tucked up inside their feathers.

Women are all right, too. They live behind veils and inside windowless carriages. They are forces of nature—though you wouldn’t know it—for they carry the old fire as well. But they have learned how to tame their power, and how to set it loose. Mostly the former, though. Mostly, they keep it quiet and coiled tight inside them, and only let this power out when it is safe—when they are alone, or when they are with their sisters behind heavy closed doors.

Because that is the way it is supposed to be. So say the laws of Aurestra. So say the frowning men. So say the looks on boys’ faces, wide-eyed and fearful, because they have been taught by their fathers about the dangers of girls—if the girl has not been raised right, that is. A girl like that might give in to her power.

So the wind ignores women. The wind doesn’t have the patience for them, with their veils and their whispers, and how they have hidden themselves away.

Girls, though—girls are only just beginning to understand the power they carry inside them, and so they must be watched over, and taught carefully by their mothers. And though a girl might be bursting with secrets, she must never shout them, shriek them, howl them to the wind, even if that’s exactly what her blood and bones are telling her to do.

Because the wind cares nothing for the laws of Aurestra. Single-minded, the wind longs for the way things used to be, when the world was ruled by queens. When girls ran wild, without veils, with bare feet, with hair long and tangled, with hearts open and loving, wanting to be kissed.

For some time now, the wind has been waiting for a girl to come along—the right kind of girl for the wind; the wrong kind of girl for the grim, white-haired kings of Aurestra.

A girl with secrets on the tip of her tongue.

A girl with power at the tips of her fingers.

A girl like Miranda.

*

Miranda walks through Aurestra’s central market. She is only twelve years old, but she feels heavy and burdened like an old woman. For most girls, it isn’t so hard to stay quiet. Or it is hard, but manageable, at least.

Not so for Miranda.

Staying quiet, staying soft, staying still, still, still has been eating away at her since she reached the Age of Refinement and was given her first veil.

Miranda wants to run, but she doesn’t.

No. She wants to race, to tear along the cobbled pavement until her feet hurt. She wants to yell, and sing—not the lilting, warbling tunes her stiff-robed tutor forces her to learn. No, something else, something different. Something that would shock her fellow shoppers and bring the censors out from the courts to seize her. A howling, savage, discordant song.

Like the wind.

Like the wind gliding softly through the winding aisles of the marketplace—tickling her fingers when she reaches for an apple, a plum; her fingers are the only parts of her not covered in fabric.

Like the wind, but a hundred times stronger than it is right now.

A thunderstorm wind. A hurricane wind. A song like that.

Miranda saw a hurricane once. It was dreadful. She was safe in her father’s sturdy stone cottage, and from the attic window, she could see the southern bay. The water surged in waves, destroying the docks. The wind knocked the boats together like they were less than toys, tearing them apart into splinters and planks.

It was dreadful, yes—and beautiful, too. Miranda had watched, her nose pressed to the crack in the boarded-up window, and she had not been able to help it:

She had let out a horrible, soft, desperate cry.

These winds, these winds, this power—this was what lay cooped up inside her. This was what she was not allowed, never allowed, to touch. If she did, if she broke the law and let it loose, what would become of her? Of her mother?

The Aurestran kings were not known for their mercy.

So Miranda cried, alone in the attic—but not the soft, delicate tears of a wounded damsel. Deep, wild sobs that wrenched her throat into knots, and the sounds of the hurricane drowned it out so that no one downstairs could hear her.

But the wind heard her. It heard her and thought, Ah. Could this be the girl? The wind thought it just might be, but it did nothing. The wind must wait for her to come to it. That was the way of things; a wind cannot just approach a girl and whisper terrible things across her skin, and coax her to tear down her kingdom.

The girl must find the wind herself. First, before anything else, the girl must tell the wind her secrets. That will be the invitation.

From then on, the wind watched Miranda.

It knocked against her window at night, and when she went to look out, she found no one there. And when she returned to bed, her skin was hot and itchy, and her dreams were restless.

When Miranda took her horse out to the fields to check on her father’s sheep, the wind chased at her heels, whipping her veil around her.

And when Miranda is twelve years old and in the market, when she brings her fingers out from beneath her cloak to grab a plum, the wind teases her skin.

And Miranda can bear it no longer.

She hurries as quickly as she dares to the outskirts, and then down the path leading north to the woods, and once she is out of sight, she runs. She runs, she tears, she flies. She drops her wrapped parcels from the market, and she tears her skirts on brambles. By the time she stops to catch her breath, she has reached one of the high meadows, in the foothills. She rips her veil from her head, and she falls to her knees, and screams.

Maybe there are farmers nearby, or shepherds, who happen to be close enough to hear her. They will report her to the censors, and she will be hanged in the square as people throw stones at her and scream for justice.

But Miranda doesn’t care.

“I have power inside me,” she whispers—to no one, she thinks. “And I am tired of hiding it. I don’t want to hide it. I shouldn’t have to hide it. It is me, and I am it, and this is how things are supposed to be. Girls are supposed to be wild. Women are not supposed to hide. There should be queens, not kings. I know the old stories. I know of the old country. I know about the old fire and the ancient storms. Why must I pretend that I don’t? Why must I lie? Why must I hide?”

The words spill out of her, held back too long, and the impact of hearing her own voice speaking treason is so tremendous that she begins to sob and laugh at the same time. Exhaustion claims her, and she lays back in the grasses and stares at the sky, knowing she must soon get dressed and return to town. Knowing her father will beat her for bruising the fruit she bought today.

And the wind watches, and is pleased. The invitation has been sent.

“You don’t have to hide,” it whispers to her.

Miranda shoots upright. “Who’s there?” She hadn’t cared, before—but now that she has calmed, the fear of being caught is like a wild animal in her chest. She finds her veil and tries to put it back on, but the wind tears it from her fingers and flings it into the mountains.

And without her veil, even though explaining how she lost it will be worse—much worse—than explaining the ruined fruit, Miranda feels taller, larger, stronger.

“Who’s there?” she demands. “Show yourself.”

“I’m afraid I can’t,” says the wind, “for I have no body. I have only an offer of friendship, and a proposal.”

Miranda’s eyes narrow. “What kind of a proposal? And why do you want to be friends with me?”

“I want to be friends with you,” the wind hisses through the meadow grasses, “because you are wild, like me.”

“I am not wild,” Miranda protests automatically.

The wind snaps at her furiously, flinging dirt into her eyes. “You can’t lie to me. You can lie to the others, but not to me. I know what you really are.”

Miranda licks her lips, though she doesn’t want to appear too interested. What if a shepherd is watching from the trees? A girl, talking to nothing? She would be hanged for madness. “And what is that?” she asks.

“You’re a girl. You’re a wild, wild girl. You have the old fire and the ancient storms in your blood. You have the power to raze mountains and part oceans. You have the power, but they have taken it from you, because they are afraid of what you could do to them. Too many years have passed between now and then, between now and the old world, when women wore the crowns and girls ran free. But it’s time, now.”

The wind sighs across Miranda’s bare legs, comforting her, enticing her. “It’s time now,” the wind continues, “don’t you see? That is my proposal. It’s time to change things. Do you know, you are the first girl in a thousand years to spill her secrets to the wind? It had to be you, coming to me. I cannot do it on my own. That is the way of things. The girl must come to me, and realize who she is—what she is—and then, only then, can I help her.”

The wind is lonely—frustrated and mighty and dangerous. Mischievous. Not entirely trustworthy, perhaps. Miranda can hear these things in its voice. But Miranda isn’t afraid. This is what she has been waiting for, even if she didn’t know it would be exactly this. This is what she has prayed for. This is what she has been secretly thinking during her lessons, while her tutor drones on and on with his watery eyes on her—like she is a bug and he is a bird who might crush her if he decides he is hungry.

“If you tell me what to do,” the wind continues, shishing and shushing across the meadow, “I will do it. No one else can tell the wind what to do but a wild girl. No one else can change things but me—and you.”

“Will it hurt people?” asks Miranda. “Will it hurt people, what we do?”

“Some. Not all, but some. Some hurt is necessary, for the kind of change we need. Don’t you see that, Miranda? Don’t you think it is so?”

Miranda thinks for a long time, sitting there, bare-legged and barefooted in the meadow, until the sun sets and the sky is awash with flame. She will have some serious explaining to do when she gets home. Some girls might throw themselves in the river instead of face their father’s wrath.

But Miranda is not one of them.

And it isn’t like she wants to hurt people, but . . . but . . . haven’t they hurt her? How many hangings has she been forced to attend? How many stones has her father forced her to throw?

Too many.

Miranda’s hands curl into fists, and a spark lights inside her.

“All right,” she tells the wind at last, “all right, I will do it.”

Then she begins the journey back to town, not bothering to find her shoes, not bothering to search for her veil or her parcels. The more steps she takes, the faster she walks, until she is running, racing, tearing down the path to her gleaming city, with fire in her blood and storms in her eyes.

And the wind churns after her, laughing at her heels.

*

The grocer—he’s the one who triggers it.

Unfortunate enough to be nearest the outskirts when Miranda comes running.

Shocked enough to drop his armful of vegetables at the sight of this girl—without her veil, barefoot, her skirts torn.

Foolish enough to seize her arm as she races by, and scold her for her impropriety.

“I’ll ring for the censors,” he shouts. “Have you lost your mind, girl?”

Miranda is used to being grabbed, used to being struck and scolded and ordered about—but that was before, and this is now. Now, she has a wind at her back. Now, her fingers are on fire with something she will no longer contain.

Truly—her fingers are on fire.

The grocer sees the sparks erupting from her hands and releases her, tries to run—but Miranda is too quick for that.

“Go inside him,” she hisses, in a voice that would scandalize her tutor, for it is coarse and lacks any sort of decorum.

And the wind obeys.

It shoots past Miranda, gathering up all her fire, stretching it out from her fingers into the air, down the grocer’s throat, down his nose, up his fingernails, into his eyes.

The power is Miranda’s—old and immense. But the wind takes it to where it needs to be, like an invisible chariot. The wind, who knows Miranda’s secrets. The wind, who, like her, is tired and angry. The wind, who, unlike her, will take much pleasure in the days to come—days of fire and storms and pain.

In truth, it would not take more than this—this one man, this one burst of fire—to change things. It is enough, this one death, to get the attention of Aurestra’s kings.

But Miranda doesn’t know that. And the wind is not going to tell her.

Instead it will race along at her heels, whispering encouragement, as she tears through the city, and the palace, and the calloused flesh of her father’s cruel, meaty fists.

And then what? When all is ash and Miranda’s fire dims, and she understands, exhausted, streaked with strangers’ blood, what she has done?

The wind considers that, for a fleeting moment, as it brings Miranda’s storms crashing through the windows of the censors’ courts—but then, as is the way with wind, as soon as the thought has come, it has gone, and all it knows is its own laughter.

The North Wind Doth Blow

When Curator Catmull was a girl, which was, perhaps, in the late 19th century, she particularly cherished the book At the Back of the North Wind, by George MacDonald. So the tale below interested her particularly, as it casts a much different light on the North Wind of that book, who so tenderly cared for a dying boy named Diamond.

Perhaps she never recovered from his loss. If so, what awfully bad luck for the children of this age.

The wind raced behind Ruby, chasing up the street from tree to tree. As she reached her door, it caught her, tangling her hair into her face as she fumbled with the key. The windchime bounced and jangled overhead, and her phone chimed in her pocket.

In the stillness inside, she read the text: Working late sorry sweet. Lasagna in fridge (is delish). Say it with me: TV stays dark till homework done. I love you. Ruby texted back an emoji sticking out its tongue, to indicate her feelings about homework and being home alone.

In some ways, though, she wasn’t so sorry to put off seeing her mother, after what had happened today.

An hour later at the kitchen table, a half-eaten plate of lasagna sat next to her math book, and her pencil scritched away on a problem. It was already dark outside, or nearly. The windchime jangled again, more insistent now.

The lasagna sat heavy on Ruby’s stomach. She had spent some time the principal’s office that afternoon. It wasn’t 100% that she was going to be suspended, but it wasn’t looking good, either, and her mother would have to take off to come for a meeting the next day, and that would not go over well.

Ruby knew she shouldn’t lose her temper. But also: people shouldn’t talk to her that way. Not people wearing prissy little perfect white dresses; not when she was holding a full lunch tray containing a sloppy joe, a bowl of tomato soup, and mess of chocolate pudding.

Her pencil worked more furiously. What was I supposed to do.

Scritch, scritch.

The windchime’s jangle became more urgent, like a warning. The wind was picking up, had found a voice, as it swept and whined around the corners of the house. Ohh, said the wind. Ohhh, oohhhhhhh, OHHH.

Even inside, it felt colder, and Ruby put her sweater back on. The whole house was dark except for the little pool of light where she sat. She cleared her dishes, turning on the kitchen lights as she passed, stuck the plate in the dishwasher, lasagna back in the fridge

SSssssssssssssss, said the wind. SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSssssssssssssssss aahhhhhhhhhhhh.

Ruby turned on the living room lamp for good measure and returned to the kitchen table. For a few minutes she worked at her math again, but it was impossible to concentrate with that wind. Fine. No choice. She took her homework to the couch and grabbed the remote. Something dumb on TV would drown out the wind and help her concentrate. That was cheating a little, but so what.

If Mom wants me to do my homework first, she should be here to make the house not so scary and weird.

The flat black screen filled with color and laughter. Outside, the wind rose and wailed louder. No more ohhh and sssssss — now the windchime jangled like a fire alarm, now the voice of the wind was a howl. Ruby pulled a throw blanket around her shoulders and turned the television up. A man on screen turned slowly to the camera with a round O mouth. The audience laughed.

Then the screen went black. Everything went black. Outside, the wind screamed and bent the air like you bend a saw.

Eyes wide in the darkness, Ruby huddled on the couch, feeling around for her phone so she could text her mom: electricity’s out, what do I do?

The wind’s scream rose higher and higher, insistent and mad.

And then, without warning, the picture window exploded. Shards of glass tore through the curtains, ripping them to the floor. The wind screamed, and Ruby screamed, too.

Then: silence. The wind stopped. And Ruby stopped; but her mouth stayed wide open.

Standing before her, luminous in the weak streetlight, was a tall woman, almost as tall as the ceiling. Her icy white hair floated all around her head. Long, ice-blue robes and scarves floated around her. Her eyes were black as holes, and she was smiling, and her face was pale blue, quite beautiful, and entirely mad.

“Diamond,” she said. “Come, my Diamond.”

“My name is Ruby,” whispered Ruby. Her teeth chattered in the near-darkness.

“But I will call you Diamond,” said the blue woman. Her voice was low and rich, with a hint of howls and whines and roars behind it. “I will call you Diamond, because I miss my Diamond. Come, Diamond, come see my world.”

“No, I want to stay,” said Ruby. She pulled the blanket to cover her face. It isn’t real. It isn’t real.

The blanket was ripped from her hands, and the woman’s huge, furious face was inches away. “Climb on my back, my Diamond, before I grow angry. Climb on my back, and I will show you the world, and what I make of it.”

“Please, I don’t want . . .” Ruby began. But a huge, invisible hand seized her; a wind as muscular as a python swept tight around her. Within seconds, it dragged her through the window and into the night sky.

Ruby found herself lying face down on the tall woman’s back—the tall woman who was far, far taller now. She clung to the woman’s ice-white hair, trying to find her breath. Clouds pushed aside as they rushed through; the world below was small dark squares and twinkling golden lights. Ruby’s stomach turned over and she closed her eyes.

“Are you happy, my Diamond?” called the wild, mad voice. “Is my world glorious?”

A sound emerged out of the roaring, keening air: a roaring sound, but mechanical, deafening, and familiar. Ruby opened her eyes.

The North Wind had overtaken an airplane and was playing with it. Ruby and the wind swept around and around the plane, slamming one wing with a sudden blast, then diving beneath its nose, then pushing up on the tail. The plane bucked and reared, rocking on its wings. Streaking past, Ruby saw through yellow windows mouths open in terrified screams, passengers struck by flying books and laptops.

“Please stop!” Ruby screamed into the howl of the engine and wind.

They flew just inches from the face of a young woman clutching an infant to her chest. Both the woman and the infant had their eyes tight shut and mouths wide open, sobbing. At another window, a man bent over, frantically texting, as the man next to him threw up.

The wind grew bored, swept on. Ruby turned, trying to see if the pilots had managed to keep control, if the plane was still aloft, oh please, please let it be. But she saw only the clouds closing behind them.

The wind flew over a black and moonlit ocean. As they descended, the waves whipped up, higher and higher, high as skyscrapers, reaching upward. “COME,” cried the wind, in her deepest howl. “COME. COME. COME.” The whole ocean rocked towards her.

In horror, Ruby spotted a ship caught between two skyscraper waves. As it foundered and tilted, tiny figures ran across the deck, unhooking lifeboats that broke free and sank uselessly into the black water. Another enormous wave swelled up, sucking the ship towards itself. Even through the wind’s wail, Ruby heard the sailors’ thin, terrified cries.

The North Wind laughed her howling laugh.

“No more,” whispered Ruby into the cold white hair she clung to. But the wind ran on.

Ruby saw many terrible sights, that long night.

At the edge of a small town, the North Wind became a tornado and turned a pretty yellow house into a pile of broken sticks. Afterwards, one curling hand thrust from beneath the wreckage. A dirty toddler sat beside the hand, pulling on it, crying.

In a blinding snowstorm on a deserted road, Ruby saw a couple in a stalled car, wrapped in each other’s arms, his coat around her shoulders. Both were as blue-white as the wind, and purple around the lips.

“Take me home,” wept Ruby into the snowy hair. Her tears froze into hard bits of ice.

In time, the wind did take her home. As light dawned at the horizon’s edge, Ruby saw her own street, saw through a smashed window her mother on the couch, blowing her nose, surrounded by police officers.

As they sank toward the house, the North Wind turned her mad smile toward Ruby and whispered in the girl’s ear. Then she slipped her gently onto her own front yard and swept away.

***

The police said “hypothermia” and called an ambulance. Her mother wrapped Ruby first in a blanket and then in her arms as they waited. “But I don’t understand what happened, love, I don’t see—and your hair, how did your hair get this way? We’ll have to cut it off, it will never comb out.”

Ruby stood still as stone, her eyes black and wide.

“Darling, say something,” said her mother. “Sweet girl, you’re scaring me. Please speak, if you can.”

“‘I’ll be back,’” Ruby whispered. “That’s what she said. She’ll said ‘I’ll be back tomorrow night, my new Ruby Diamond. And I’ll be back the next night, too, and the next, and the next. I love you, my Diamond, and I’ll be back every night, as long as you live.’”

Laughter

Around the world, I am known by many names, and I show many faces.

Faces you never see. And really, it doesn’t matter what I’m called.

In winter, when I’m cold and brittle and snap at the skin of anyone foolish enough to step outside, people close their doors and seal their windows against me. I howl and scram, hammer against the glass, bide my time.

There is a particular smell when the first hint of spring comes in on the air. I smile—for I can smile, you know—and wait. Just a little longer. Soon, so soon, people will throw open their homes to invite me in, and this…this is a mistake.

“What a lovely breeze,” they say.

Hahahaha.

I can laugh, too. You hear it all the time.

When I’m warm again, I am as young and playful as all the other creatures of spring…at first. I dance through the trees, flicking each freshly-sprouted leaf, and ruffle hair on hatless heads. It’s delightful. It’s fun. And I do so enjoy having fun. I gust into parlors and kitchens, cackling as that vase just too close to the edge of the countertop tumbles to the floor with a smash, or stay outside to flip over all the chairs on the grass, one by one.

But spring crawls toward summer. The long, hot days of summer when boredom is as dull and brown and dead as the flowers burned to a crisp in their dry, dusty flowerbeds. I must wait again, then, but only until nightfall. The sky darkens and the air cools enough to let me dance again. Through open windows and into the dreams of sleeping children.

Children are easiest, you see.

And then, then I watch.

~*~

Emily Lewis awoke grumpy and hot. The wind had woken her in the middle of the night, whispering in her ear, blowing across her skin until she’d gotten cold and pulled the covers all the way over her head just before falling asleep again. Now, she was positively boiling, and she stomped downstairs to the breakfast table with a scowl on her face.

“Good morning, sweetheart,” said her mother.

Emily pushed over her glass of orange juice. “Oops,” she said, as it spread slowly, stickily, ruining the fine white tablecloth.

“Emily! Be more careful. Here, it’s all right, I’ll clean it up.”

On the other side of town, little Nate Winston waited until his father was busy washing the already spotless car outside. He fetched a chair that wouldn’t wobble and stood on the very tips of his toes at his bedroom window, pulling down the coverings that had rattled in the wind in the middle of the night. Strings broke and plastic cracked and they fell in a heap on the carpet, utterly ruined.

In the next city over, Bethany Bertram sat in the garden and plucked each petal from her mother’s prize-winning roses, one by one. They scattered on the lawn in droplets of blood red and sunshine yellow, and she hid in her room when her mother came home from work. Slowly, they dried out, turning black and papery in the heat as another long, hot week with no wind began.

The summer dragged on. The wind came and went, always in the night, and hid well away from the burning sun. Everywhere, little children woke in foul tempers, and their parents went to sleep that way.

~*~

I did tell you I like fun, but even these small amusements aren’t enough, in the end. How could they be, for one such as myself? For an hour or a day, perhaps, but soon I must begin to think of the memories that will have to get me through the long, cold winter, when people stay indoors and shut me outside.

I am generous. I give them ten whole days with not so much as a breath, not a single puff of air to rustle even a single leaf. I watch the people wilt as surely as the flowers do.

Every window for miles is open, just in case. Waiting to invite me in, should I decide to turn up.

Hahahaha.

There’s no time. There never is. Emily Lewis’s mother hears the screen door leading to the porch start to rattle on its hinges. Nate’s new curtains begin to billow into the room. Bethany sees the new roses shake on their thorny stems.

A window breaks.

A branch, already cracked, snaps from its tree with a sound like thunder and just barely misses the head of a man walking underneath.

“Get inside!” come shouts from everywhere. “Close the windows! Going to be an awful storm!”

They try. Oh, they do try. I dance as fast as I can to the music of splintering wood and shattering glass. Blades of grass whip through the air, sharp as knives of steel. Through the towns and cities I race, gathering speed, gathering fury to warm me during the loneliness of winter. I do not look behind me at the wreckage in my wake, the things fallen, broken, beyond repair. They will fix their doors and windows in time, seal the cracks in their houses against me.

They always do.

When the first bite of autumn comes, I return, carrying the scent of smoke and the promise of a chill. I flicker through the trees, kicking at the last, stubborn, curly-edged few that cling to the wood. I swoop down, swirl through the red-gold piles on the ground, rustling and spinning.

If you listen on a clear autumn day to the crackle of the leaves, you will know what my laughter sounds like.

Hahahaha.

The Interview

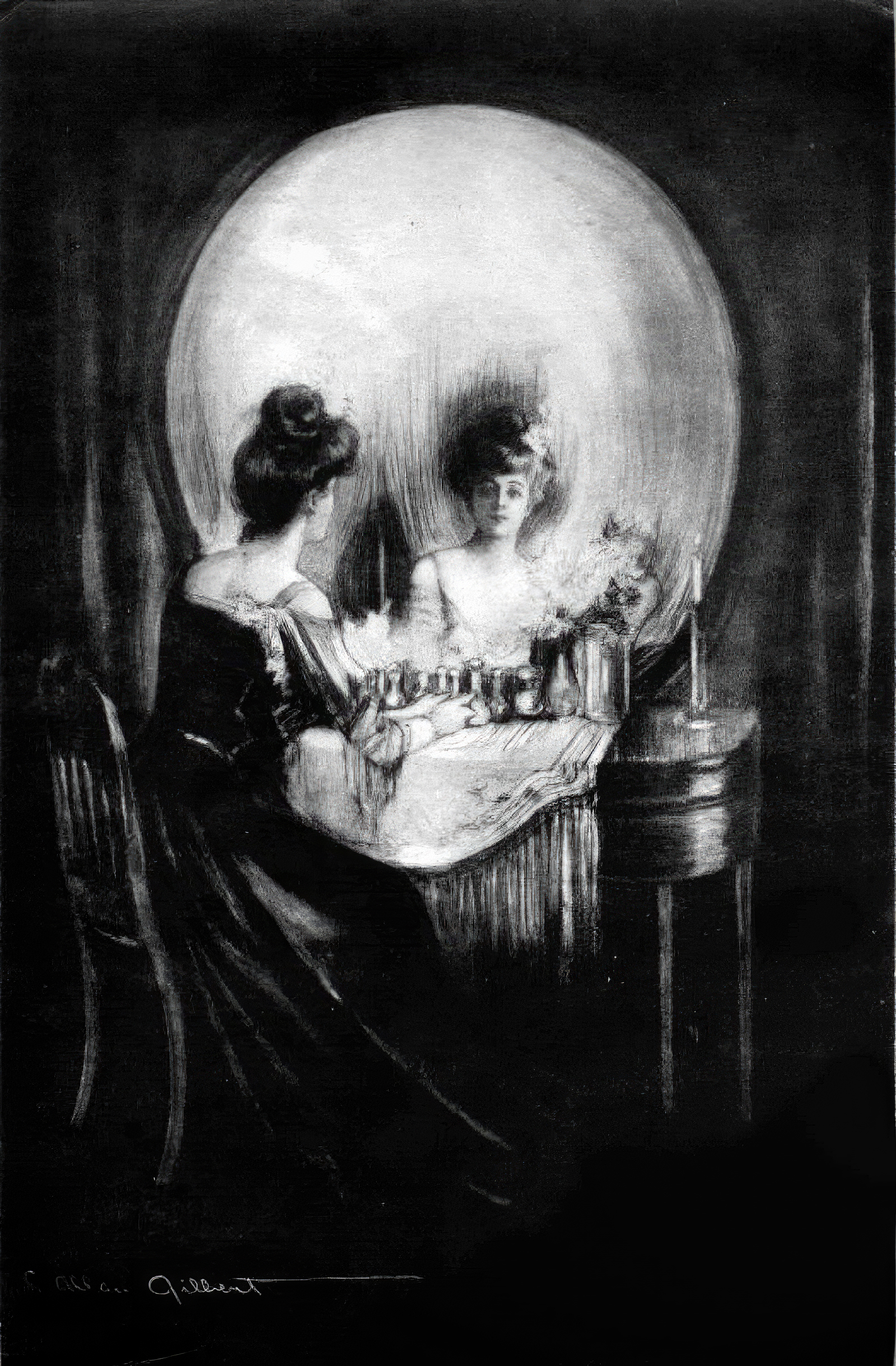

All is Vanity – Charles Allan Gilbert

Marisol Tublé was 107 years old, and so it felt like something of an affront to wake up in a strange and extravagant hotel room with a headache and no recollection of how she had come to be there. Headaches were the ailment of the young and lazy, Marisol thought, for people who drank too much or did not want to listen to tiresome piano-playing relatives. At 107 one ought to have graduated to more noble illnesses.

She lay in the bed, her wrist against her forehead, staring up through the semi-gloom at a ceiling of painted panels and trying to recall what she had to do to today. There had been such a lot of traveling the past few weeks. She remembered that much. She was a singer—the Great Warbler Marisol—and she was on a tour. Her final tour. A sudden throb passed through her head and she had a brief impression of concerts, one after the next, the hustle and bustle behind stage, the murmur of the audience as they settled into their cradle of anticipation, the flare of the stage lights, the swell of the orchestra, and the swell of her heart the beat before she began to sing, Budapest, Rome, Darmstadt. . . But where was she today?

She rolled over and squinted at the silver clock on the nightstand. She couldn’t see its numbers. It was a blurry, ticking moon, too far away. She dragged herself closer and stared at its blank face. Her old, old eyes flickered over the spiny hands. Then she let out a small squeak and sat straight up, her frail frame like a pole in the dark.

Nine o’ clock. It was nine o’ clock in the morning, and faint, butter-colored light was slipping through the slit in the drapes, and she could hear the distant calls of birds and people. Marisol remembered: she had been on the final leg of her tour, almost done, and then there had been some unpleasant incidents, and she had been invited to visit one of those small, dusty countries that no one really knows exists, and to perform a concert there, as well as a brief conference to speak to the local press. That was it. She was staying at a hotel on the Rue de Marmiet, and her contact, a man named Mr. Devereux was to pick her up at 9 thirty from the lobby to take her to her interviews. Which left her with only thirty minutes to prepare herself and take her breakfast.

Ah well. The stage waits for no man. Or was it ‘Death waits for no man?’ There was no great difference.

She began to struggle out from among the sheets, heavy, scratchy, frilled things that smelled of must and rose-petals. She kicked them all onto the floor, slid off the bed, hurried for her dressing gown. . . .

It was odd that she had forgotten where she was. She could remember things from her childhood, clear as a glass of water, could remember stumbling on a curb on a hot summer day and losing an ice-cream cone to the muck of a gutter. She could remember her mother, playing piano, teaching Marisol to sing. But she could not remember where her performances were one day to the next. She frowned and began taking the curlers from her hair and rowing them up on the top of her vanity.

She felt very tired still, and the headache hadn’t left her. She hoped the interviews would go quickly and that the journalists would be pleasant. She began shuffling through the contents of an alligator-skin cosmetics case, bottles of tincture and clasps of powder clinking together softly beneath her fingers. She brought out an elaborate perfume-diffuser and poof’d a cloud of violet-smelling mist onto her neck. One time, twice, again and again. Yes, she hoped very much the journalists were pleasant.

* * *

It took Marisol about twenty minutes to prepare herself, and that was in a great rush, without the attention to detail she usually gave herself. She painted her paper-thin skin very carefully, white as porcelain, with lead and bone-powder. She dabbed her lips and rouged her cheeks. She put on strings of pearls and a small hat, and when she was all finished she raised her head and smiled at herself in the mirror. Her face was a thousand hatches and cross-hatches, and she had not so much crow’s feet around her eyes, as octopus feet. But when she smiled, even in the silence and of the dim hotel room, her face turned glowing. Her eyes flashed, piercing and charming and witty and warm all at once, and had anyone been watching at that moment, her gaze would have struck home like a bolt of lightning.

The look faded as quickly as it had come. Marisol’s eyes dulled a little. She began puttering about.

Interviews. Interviews, and then a concert. And then she was almost done.

She adjusted her hat put on a pair of gloves, and then she let herself out of the room and went downstairs to the breakfast room. It was already 9 thirty by then, but it was not good to be early to anything, especially when meeting people one didn’t know.

Marisol had four bites of toast and three cups of black coffee in the breakfast room. It was a very shabby breakfast room. And empty. It might have been grand once, but it was difficult to tell because it was so dim, and there were great, many-ruffled drapes over the windows. The only person in the room was an attendant standing by the buffet, still as a statue. Marisol watched him as she nibbled at her bread, and drank the last of her coffee. Then she set down her napkin and hobbled out of the room. She found Mr. Deveraux waiting for her in the lobby.

“Mr. Deveraux,” she said, coming up to him and smiling again, that brilliant, flashing smile. “I hope all the preparations have been made in my dressing room for this evening?”

Marisol always asked that there be a bottle of Mr. Thymus’s Throat Soothing Syrup, as well as six pink roses and a piece of chocolate waiting for her after every concert. She didn’t really like chocolate, or pink roses for that matter, but if she didn’t ask anything people tended to get lazy.

Mr. Deveraux looked at her curiously when she spoke. Then he nodded and gestured for her to follow. He was a small man, and he seemed rather nervous. Marisol thought that was just as well. Nervous people were much easier to handle than confident people. He did look vaguely familiar, though. She watched him as she followed him through the glass doors and into the street. Perhaps it was just another old memory, a snippet of someone long dead. Perhaps it was not even that.

Mr. Deveraux escorted her along the street, through the sticky morning air. It was not a hot day, but it was one of those uncomfortable mornings where the heat was just enough to make one scratchy and sweaty simply by existing. The street was deserted. Quite as empty as the hotel’s breakfast room had been. It was lined with shops, shuttered and closed, a city hall, a cathedral and several cafes. Marisol could not hear the birds anymore, or the call of the people. It was utterly silent here.

Mr. Deveraux led her into the shadows of a promenade, past a beetle-black automobile and some dying palm trees, down a stretch of cobbles, waiting every few steps for Marisol to catch up.

Marisol didn’t hurry. She never hurried anywhere, not anymore. She looked around her with great interest, and whenever Mr. Deveraux looked at her with those questioning eyes of his, she smiled at him and continued to feign enjoyment of the scenery. They arrived, at last, at a tall, terracotta-colored building, and Marisol followed Mr. Deveraux up a flight of steep steps, ever-so-slowly, down a short hallway, and into a room furnished with two hard wooden chairs, a table, a vase of dead flowers, and nothing else.

Marisol frowned. This was a sad country indeed if this the best they could do. Why had the journalists not simply met her in the hotel? But again, ah well. One must be understanding of other people’s customs. Marisol stepped into the room and sat down on one of the chairs.

“I suppose we’d better get on with it then,” she said, and breathed deeply as though steeling herself for a great trial. “Please show them in one at a time, Mr. Deveraux.” Then she smiled one more time at him, and said began fanning herself with a small feathery fan.

“Y- yes,” said Mr. Deveraux, and peered at her again, and darted out. What an odd man, Marisol thought, turning her attention to a small window in the wall. It could be that Mr. Deveraux never seen an opera star before. Or perhaps her make-up was slipping. The heat was just enough to do that. She began quickly touching about her eyes and hair, and then the door opened and she dropped her hands into her lap.

Mr. Deveraux poked his head in. “Erm- ” he said.

“Yes?” said Marisol. She was beginning to feel somewhat annoyed. It was not a good day to be sitting in an ugly, stuffy room. She needed to begin practicing her scales. And why was everything so empty and desolate here? She still could not hear the sounds of a town through the window, and the birds were silent, too.

“Yes, erm . . . The journalist is here.”

Marisol clicked her tongue. “Yes, show them in. Quickly, please. I’d like to get back to the hotel as soon as I possibly can.”

Mr. Deveraux nodded, but he did not leave. He adjusted his collar. Finally he said: “There is only one to see you today, Marisol.”

Marisol paused her fanning, eying him. “Only one journalist?”

Mr. Deveraux nodded.

Marisol stared. That couldn’t be. Was there only one newspaper in this country? Granted, she was not in her prime any more, but that there should be so few interested in the Viennese Nightingale, the Star of Copenhagen, the Great Warbler? That was very nearly insulting.

“Yes, yes, all right,” she said, a bit testily. “Who needs a lot of journalists anyway? The sooner we’re finished the better. Show him in.”

Mr. Deveraux ducked his head and hurried out of the room. A few seconds later he returned, bringing with him a man. Or at least, something vaguely human-shaped.

The man who came in was not very much like a man at all really, or even much like a journalist, and the sight of him made Marisol flinch in her chair so hard that it creaked.

The man-thing was very stooped. He had a great, warty mushroom going out of the side of his head, his eyes were rheumy, and his skin was sagging in all the wrong places, so that it looked like a wet bag draped across his skull. His coat was covered in moss and barnacles, rooted in deep blue cloth. He came in, clumping over the floor, and settled himself heavily opposite her.

Marisol leaned forward, squinting. “You- you are the journalist?” she asked quizzically, and then looked to Mr. Deveraux. But Mr. Deveraux had already fled.

The man-thing watched her for several seconds, his eyes blunt and heavy. Marisol watched him back. She paid careful attention to the mushroom growing from his face, which seemed to be changing colors slowly from russet to deep-green.

“Please ask me questions, then,” Marisol said. “I haven’t got all day. If you’re the only one here, I’d like to be finished very soon. How long do you think you will need?”

Here the man-thing cleared his throat wetly and said, “I will ask the questions,” and took out an old pad of paper and a lead and began scribbling away at it. Marisol gasped. I will ask the questions? Did he mean that simply as a preamble to his question-asking, or was he telling her that he would be the only one asking questions, and therefore would not answer hers?

In which case he was being very rude. “I beg your pardon?” she said angrily, and hammered one heel on the floor.

“You have a concert tonight, then?” asked the man-thing, ignoring her question. “You are going to sing for a great audience?”

The man-thing spoke very quickly and only looked at her briefly, and all the while he scribbled in a notepad in his hands, though Marisol had not yet answered with a single word.

Marisol stared at him, her hands clasped tight in her lap. What in all earth? “Mr.- Mr. whoever you are, I am a singer, and you are a reporter, and it is your business to ask me questions that are not stupid. Proceed.”

The man-thing looked up at her quickly, then down. “Are you a good singer? Have you been singing a long time? Perhaps as a job?”

Oh, thought Marisol. She knew what game he was playing. It was one she had come across many times before. The envious, faintly aggressive sort, who made a point of being ignorant of everything his subject had ever done, in order to make his subject feel small and insignificant. Well, Marisol was beyond that. She had met all the varieties of writers and journalists in her interviews throughout the years—sorts who smiled very wide and then wrote articles all of black slashes and bits of hate, sorts who were cold and aloof, sorts who were callow and eager, and asked far too many questions, so that she had to flap them away like flies. This was just another kind, this envious creature. Perhaps the man-thing was a singer, too, and was deemed too ugly for the stage. There was the saying that if you could not do, you taught. Equally true might be: if you could not live, you wrote.

“You are clearly new at this job,” said Marisol sharply, at which the man-thing looked up with some irritation. “I suggest you research journalism and proper etiquette and how to remove fungi from your face, and then perhaps we can speak again after my concert this evening.” She stood, swaying a little on her feet.

“What do you remember about yesterday?” asked the man-thing, not moving at all.

Marisol ignored him, making her way slowly toward the door.

“Fine then, what do you remember from last week? Were you happy last week? Or were you sad. Perhaps you were sad. A bit depressed, even.”

What a perfectly foolish question for a newspaper article. But then newspapers weren’t what they used to be. People didn’t want information. They wanted stories. Exciting stories. Tragic stories. Funny stories. False stories.

Marisol reached the door and tried to open it. It wouldn’t budge. It was locked. She wheeled around on the man-thing, who still hunched over his pad, back toward her, scribbling.

“Do you like it here?” he went on. “Or would you rather be somewhere else?”

Marisol was trembling now, part with rage and part with fear. How dare he? Why had she even come? What was this wretched city and its wretched hotel? “It is ghastly here,” she spat, not even thinking. “You are ghastly. The hotel is ghastly. I hate it. I hate all of it. I am leaving the moment my concert is done, and you can be sure I will have nothing pleasant to say of you when I am home again. Now, I demand you let me out.”

The man-thing did not move a muscle. Scritch-scratch-scratch went the nib of his pen, and the ink splattered.

“Mr. Deveraux!” screeched Marisol, and it almost killed her to do it because screeching was not good for the vocal chords. “Mr. Deveraux?”

The man-thing didn’t look up. “What time is your concert tonight?”

“I am not a signpost! Go and find a flyer and look it up.” Marisol began pounding against the wood, her thin hands cracking painfully on the frame.

“What are you singing?”

“The Arias from Tosca!” she screamed. “From Puccini! Let me out!”

“Do you know what happens in that opera, Mrs. Marisol? In Tosca?”

“Of course I know! I’ve sung the role a thousand times! Do you know?”

“I do. I do know. It is about a great and desperate lady, who at the end of Act 2, takes a knife and- Marisol, it’s about a person who murders another person, and then runs away.”

Marisol stopped pounding the door. She turned on the man-thing, and the man-thing turned, too, in his chair and looked at her with his mournful eyes and hideous face. Marisol’s gaze was very sharp just then, and so lucid, that even the man-thing stared. And then Marisol smiled. Her last resort. Her final tactic with reticent journalists. It was a desperate, terrible smile.

“It’s all very sad, isn’t it. But the music. The music!”

The man-thing closed his pad. “Marisol,” he said gently, and he no longer seemed so dreadful. “Marisol, I am not a journalist. I am doctor. Do you remember? Do you remember anything?” Suddenly he looked rather sad, or perhaps pitying.

Marisol continued to stare at him, her smile fixed, her powdered skin cracking into tiny filigree beneath her eyes.

The man rose from his chair. He didn’t look quite so strange anymore, not even to Marisol. He didn’t even have mushroom growing out of his face. And his coat was the blue of a uniform, wasn’t it. No moss or barnacles. A blue uniform with a red cross above the heart.

“You’re lost, Marisol. It has been forty years since you were last on stage. It’s been forty years since you were anywhere but here, since you took up that knife and- ”

“It’s wonderful, isn’t it,” she said, pointedly ignoring that statement. “Everyone knowing you. You know, I always thought you’d really made it when you don’t have to tell people things about you anymore and they just know.”

“Do you have any memories of your family? Who they were? Perhaps if you remembered that, we could trace someone, find someone to- ”

“There is no one,” said Marisol, and the smile dropped from her face like a stone. “There is no one left. People die. They forget. But the audience doesn’t. I’ll always have them. The audience loves me.” Her words were ferocious there, wild and sharp . . . and then her face softened again, and she looked simply tired and frail and rather annoyed, waiting to leave so that she could go and warm up her voice.

* * *

Mr. Deveraux came back to collect her after the doctor had gone. “How was the interview?” he asked, helping her from her chair.

“Odious,” said Marisol. “The journalist was a boor. I think he disliked me from the start. I don’t even want to know what the article will be like.” She began to warm up her voice even as she walked, her notes high and reedy, like a cracked whistle. She broke off a second later and began fanning herself vehemently. “He was clearly just a bitter pudding. That’s what my mother would say. A bitter, bitter pudding, all nasty and rancid. You know, I’m glad there aren’t any more reporters in this wretched town. I don’t think I could bear to speak with them. I will sing for the audience, yes, but then I’m done. I’m flying straight back to Paris. Mr. Deveraux, you may arrange the car to pick me up first thing in the morning.”

Mr. Deveraux nodded patiently.

And as they walked down the street and into the hotel, the world seemed to drift around them, disintegrating. The floral wallpaper faded to white plaster, the chandeliers wilted into iron lamps, and the drapes fell to nothing over bare and glaring windows, barred on the outside. Marisol was no longer dressed in velvet and pearls. She limped along in thin slippers over the green floor. Her clothing was a white shift. But as Mr. Deveraux brought her back to her cell on the third floor of the Belvoir Institute and guided her gently through the door, she turned and smiled at him, and there were those eyes again, diamond-bright, and her face enough to light a stage, and it made Mr. Deveraux pause for a second in awe.

“I’m ready to sing for them,” said Marisol, and her eyes flashed one more time. Then she vanished into her cell, and Mr. Deveraux closed the door behind her and locked it.

As he went away down the corridor he heard the sound of music drifting after him, the beginning notes from one of Puccini’s arias, rising, rising in a small, broken arpeggio, and for an instant he thought he heard the rustling of an audience, the breath of excitement as the stage-lights flared and the curtain began to rise. . . .