The Shoes that were Danced to Pieces

Our father is a bad man. We hate him.

He has twelve daughters, and I am the youngest. He is the king, but when he dies, none of us shall rule. He laughs at the idea. Although he has twelve daughters like twelve strong trees, like a sheaf of wheat; although we are some of us brilliant, some of us strong and fast, and some of us tenderly kind, and some of us able to talk a flock of birds or people into following wherever she leads—despite all that, he laughs at the idea of a woman ruler.

“I’d more likely leave my kingdom to my dogs,” he says.

When my oldest sister tries to lay the case for fairness, or for sanity—that he could choose one of us other than her, even, or that perhaps we could rule together, lend each of our separate strengths to lead the kingdom to a new happiness and peace (for it has seen little of either under his clumsy, brutal rule)—our father mocks her, says in a high lisping voice (and she doesn’t lisp, and her voice is low and cool), “Oh Daddy, pwease, I want to wear the pwetty crown, it will show off my pwetty shining eyes!”

We hate him. My eldest sister hates him most of all. He would never give her the tutors she begged for, so she has learned and studied in secret, all her life. She is the cleverest of us all.

Father intended to give the rulership to some stupid, brutal boy he will choose to marry one of us. But we had other plans. We said: We’ll never be married, never. Though we will not rule, we will keep our own freedom until we die.

One morning, as we lay in our twelve beds, my sister Rêve sat up straight and fast. Her eyes were shining and wild. “I have had one of my dreams,” she said. Rêve is a great dreamer, and knows how to dream things true. But all she would say was that that night, after the king our father went to bed, we should all dress in our favorite, our loveliest, our wildest dresses, and wear our dancing shoes,

We did as she said. “Now see what I dreamed,” said Rêve. She knocked three times on the wooden headboard of our eldest sister’s bed: knock, knock, knock.

For a moment, nothing happened. And then—oh, and then—the bed sank away, as if sinking into a great black lake. And beneath the bed were stone stairs, going down, down, down.

So down the stairs we went, in our clothes of ebony silk, of cherry-wine velvet, of lilac lace. Our soft dancing shoes made no noise at all on the stone steps.

At the bottom of the staircase, we entered a forest where the trees were made of filigreed silver.

Next we came through another forest, where the trees were shaped of shimmering gold, delicate gold leaves trembling as we stirred the air around them in our passing. The gold made the air feel warm.

Then we moved through a third forest, whose trees were cut from diamond. Each twig and leaf glittered hard and bright around us, and in that forest I felt as cold as if the trees were carved of ice.

We emerged onto the shore of a vast black lake, a lake that mirrored a vast black sky, so both seemed crowded with diamond stars, and no moon at all. Floating before us were twelve boats, each a different color, the colors darkened and subdued under the pale stars.

In each boat sat a young man, each quite different, skin dark or fair, but each with the same mournful smile and something ghostly around the eyes and mouth.

I chose the ghost-boy whose boat might have been sky-blue, in the light. When he helped me in, his hand was as cold as the diamond forest.

The ghost boys rowed us in perfect silence to an island where a crystal castle stood. Warm lights moved and glowed inside the castle, like fire caught behind glass.

Inside the castle was an orchestra made up of forest animals—a grave jay with a tiny violin, and a white stag with a cello, and a smiling fox on a stool with a clarinet—oh so many of them, many more. And their music was wild, and it was mournful, too. The music had fire and rage underneath it to match our fire and rage, and it made us want to do nothing but dance.

So dance we did with our cold and ghosty boys, we danced out our rage all the wild night, as the violin-bearing birds swirled above our heads, the fiery lights swirling too as we swirled in the dance, our heads flung back, our feet mad beneath us.

So dance we did with our cold and ghosty boys, we danced out our rage all the wild night, as the violin-bearing birds swirled above our heads, the fiery lights swirling too as we swirled in the dance, our heads flung back, our feet mad beneath us.

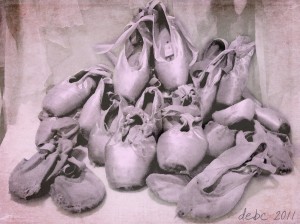

When the eastern horizon began to soften, the boys rowed us back to the edge of the lake, and we walked through the icy diamond forest, and the shimmering gold one, and the delicate silver one, and back up the stairs to our room. On the floor beside each bed, we left our shoes in shreds and pieces

The next morning, the wretched maid told our father about our shoes. He demanded to know what had happened. But we were half dead from our long night, and we said nothing at all. Even my sister who always talks back just looked at him, her face pale and empty, and turned away.

He ordered that we must be kept shod, and left. New shoes were brought that afternoon.

The next night, we went dancing again, we danced our anger, and the next and the next and the next and the next. Every morning, our new shoes lay in shreds on the floor beside each bed; every morning, our father would shout and argue and insult us.

But we were turning half-ghost ourselves by day, with all our life in the night, and we only looked at him from dark-circled eyes and yawned.

Our father made an announcement to the kingdom. Any man who could solve the mystery, he would marry off to one of us, and make his heir. But if the man tried for three nights and could not solve the mystery, he would lose his head.

“That should motivate them,” said our father. His cruelty, his cruelty.

A prince from a far land came to try. Father gave these him the room beside ours, and left the door between open, which shamed and angered us. But my clever eldest sister made a potion, and put it in fine wine, and offered it to the prince with falsely loving words.

The potion made him sleep all night, and we were left to our raging revels. He slept through three nights, bewildered each morning at how it had happened.

On the third morning, my father had his head chopped off with an axe.

My heart wavered at this, for he had not seemed a bad man, only a hopeful and arrogant one. But my eldest sister, whose rage was greater, laughed. “It is what he deserves,” she said. “It is what they all deserve.”

Then she added, so perhaps her heart was not quite eaten with anger: “Anyway, it is father who kills them, not I.”

More princes came. More princes tried. More lost their heads. My eldest sister’s laugh became uglier and too much like my father’s.

Then no men came for a long time. We danced out our rage every night. Every morning we grew paler, but our eyes were bright and hot inside their dark circles. My father’s anger grew, because something was happening that he could not control.

But that his daughters grew into ghosts before his eyes: that worried him not at all.

After a year of the dancing, a new man came to try. He was different from the others, older, and no prince at all, but a common soldier who had been wounded in the leg, so that he limped badly, and could fight no more. He told us that he had met a strange old woman and shared his food with her, and she had repaid him by telling him of our father’s offer, “as well as with advice, and a small gift.”

I did not like to hear that, for there is great power in the gratitude of strange old women.

My father said, “I hope her gift was an iron neck,” and laughed.

When my eldest sister brought this new man the doctored wine and false words, he watched her out of dark eyes, and I thought I saw something like pity in them, which confused and frightened me. But he drank—or we thought he drank. And when the night came, he slept—or we thought he slept.

And yet when we slipped down the stairs that night, I was sure I heard a heavy, uneven gait behind me.

But when I turned, I saw nothing at all.

When we passed through the silver forest, I was sure I heard the limping steps behind me still. And I did hear, I know I heard, a sudden crack, like the snapping of a branch. I looked wildly around. “It was probably an animal,” said my sister Tendresse. “Calm yourself, calm yourself.”

So I put the limping, swinging, invisible step out of my mind, and out of my hearing, and found my ghosty boy, and danced my raging dance all night in the fiery crystal palace.

The next morning, the soldier said, as they all had said, “But I don’t understand how I could have fallen asleep.” I felt better. My imagination must have been playing tricks on me—my imagination, and perhaps my too great respect for strange old women.

In the silver forest that night, when I heard the limping, broken steps behind me, I said to myself firmly: “Your imagination.”

And at the crack of the branch in the golden forest, I said to myself, “An animal.”

Still, I could not throw myself into the black lake of our dance as deeply as usual.

In the morning, the soldier said, “Only one more night! It certainly doesn’t look good for me.” So I thought it must be all right after all.

And yet that third night, the heavy, limping gait behind me felt like the gait of Death. The crack of the branch in the diamond forest thrust a shard of ice into my heart.

And as I danced, I swear as I danced with my cold, mournful, ghosty boy, I felt something touch my arm here and there, something I could not see, as if that Death walked among us in the dance.

That morning, my father came with guards to take the soldier away to be beheaded. They found him sitting politely at the edge of his neatly-made bed, holding in his lap a silver branch, a golden branch, and a diamond one. As we watched from our room in despair, he told the whole story of what we did each night, and held up the branches one at a time for proof.

The king our father laughed and laughed, and clapped the soldier too hard on his back, and jeered at us. “They want to rule the kingdom, and yet they spend their nights giggling and dancing, like the empty heads they are.”

(But he did not know, had never seen, our raging, raging dance.)

The soldier said nothing. My father stopped laughing and said, “Then take whichever you want for a wife—Bellaluna is the prettiest by far—and I’ll set you up in a castle, and then you can wait for me to die, which I hope is a long damn wait.” He walked out, the guards behind him.

The soldier turned to us with his dark, opaque eyes. He said, “I think you are all quite beautiful, and much too beautiful for a man like me. Also, I will not take or choose, as if you were toys in a shop; but I will ask, and I will offer my pledge and my faith and my respect.”

He turned to my eldest sister. “I am no longer a boy, and I wish a wife who is my equal or better in wisdom. I have been watching you for three nights, and I believe that is you. I will need your wisdom to help me make this land a more peaceful place, for I have had enough of fighting. If you will have me, I will make you my queen and co-ruler, and we will heal the kingdom together. You do not need to give me your answer now.”

And he limped away to be shown his new castle.

I watched my eldest sister that night, over the ten narrow beds of my sleeping sisters between us. She lay back with her hands behind her head and her eyes wide open, considering.

In the morning she said to us, “I do not know how to give him my trust, but I am going to give him my trust anyway. My anger has danced through too many pairs of shoes. He is a new man, and I will try a new way.”

So the banns were made and the wedding held, with great pomp and many white horses and silver lace and bells. In the following weeks we visited them at their castle, and we saw a new way between a man and a woman, that we had never conceived of before.

One by one, with our father’s shrugged permission, we moved to the new castle to live. My sister has filled it with books and art and mathematical instruments, and everything our father ever denied us. We sleep well at night, and we have lost our ghostly look, and live in the world around us.

Our father is a bad man. We hate our father.

But one day our father will die. And together with this wounded man, we we will make a new and better kingdom.

Once our father dies.

Nicely done. I like the kind of behind the scenes look at the princesses, the kindness of the soldier, and the emotions of all the characters. Great job.

Thank you so much!