A Beast Named Flowers

My dearest Curators,

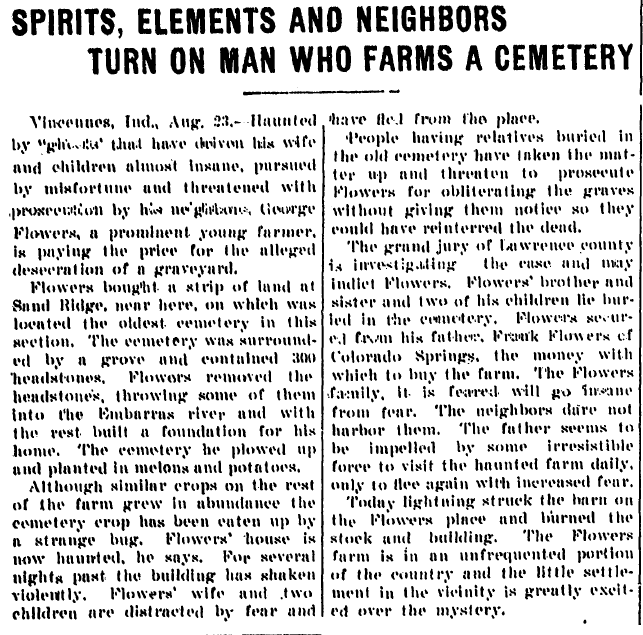

I stumbled upon this newspaper clipping whilst foraging through an abandoned farmhouse for haunted relics, as one does, and was immediately intrigued, for obvious reasons. Why a man would want to desecrate the cemetery where his own children lay buried is not something even I, with all my experience in the dark and twisted, can understand. I managed to trace the clipping’s origins back to 1902, to a small town that fits the phrase “in the middle of nowhere” better than any other “middle of nowhere” place I have encountered–and, as you know, that has been quite a few.

There, I dragged the river in an attempt to locate any of the desecrated headstones, although I did not have much hope, seeing as how over a century has passed. Fortuitously, I did find one scrap of stone that called to me more than the other scraps of stone along the riverbed–called to me quite literally, with a sharp-edged voice that I could identify as neither girl nor boy, young nor old, but rather something between and of all of those things, too. The voice in the stone babbled and hissed, croaked and raved, and truly at first it made not one whit of sense. But I think I have managed to arrange the words I could understand into a sort of story, although it is different from the others I have collected.

I have enclosed said stone in this parcel, along with the clipping and my story, all of which should of course be archived, and posthaste. Perhaps one of you will have more luck listening to the voice inside this stone and piecing together its tale. I would advise you do so quickly, for the voice fades every day. I do believe it will soon fall quiet altogether, so far from its home.

Yours,

Curator Legrand

I don’t like flowers

I never have

not the yellow ones like Mama’s hair

and not deep blue like winter mornings

not blood-red, not meat-red, not red like bad gums

they stain pockets and they turn my skin to crawling

they look happy when I am happy

but they look

cruel

when I am not

and I don’t like this new one either

this new flower who

sings

when it works

yes I do believe this new flower is

the

worst of

all

the first thing he did was

rip

he took the stones and

tore them

from the dirt

from the roots

one by

one by

one

until we had no heads

until the wind gnawed our bones bare

then what did he do? what did he do then?

I’ll tell you

he built a house with them

he spread them out like a deck of cards

or maybe more like

if you squint real hard

stacks upon stacks

of teeth

worse, though, was the others

the other ones he took

and he tossed

and he threw them in the river’s mouth

to drown

alone

their names lost to the waters of the

dead

he built his house upon them

our stolen stones

our cards

our teeth

left us cold and left us

scared

took his plow and tilled us

chopped us

churned us into chunks

pushed his seeds into us

for money

brought his wife and his babies

kissed them

hugged them

tucked them in

“this is our home now” he told them

no

wrong

it is

ours

and we want it back

he is no flower, this creature with his hat

his plow

his boots

his rake full of metal fangs

his name is that but he’s got no

petals

pollen

pistil

he has only a face made of

hard

blocks

eyes made of

sharp

lights

I think he knows

we are

here

I think

as he stabs our earth with

his plow

his shovel

his rake

he imagines he is hurting us

and is

glad

He will not be glad for long

There are many here in the dank dark deep

There’s me and sister, yes of course

and Big Bad Joe who never meant no harm but has a

face cops thought belonged

nowhere

but jail

There’s Ellis Haze whose daddy sawed off her feet

so she’d never walk away

And the Bloom boys

who knew better

There’s that girl Frankie who thought

life was

a game

And old man Lyle

And the family called Drake

And then there’s the girls with their faces

cut up

I bet Flowers

(that’s his name, but he isn’t a flower

he’s a

beast)

I bet Flowers won’t like

those cut-up girls

But he’ll like me least of all

He always did

We crawl up through the house

its steps

its rooms like hearts

its stolen stones

(OURS)

We drag our way up into the scorching world

above

(it’s like Hell up here)

(too hot and too much noise)

(too much remembering

and remembering

and remembering)

The air forgives, in the dank dark deep

The air caresses and soothes

But we

will do

no

such

thing

up here in this Hell of Flowers

(Daddy, Daddy, why’d you leave me)

(Daddy, Daddy, why’d you drop me in this

place of

stillness)

Our hands are spiders and

Our legs are worms and

Our tongues are vipers and

Our fingernails carve like that rake of yours, Mr. Flowers

that rake

that rake

that rake

Didn’t you know what you done dug up

now

didn’t you didn’t you

know

Didn’t you know my face

(half of it is yours, you know)

(Mama always said I got your eyes)

Are your walls crawling now with that black germ sir

Is that your ceiling shaking like the endtimes

Are those your babies screaming for their mama sir

Are those your babies screaming

You brought us up here into this

Hell

You shook out our sleeping veins and

laughed

You broke our chains and

drowned our names in silt

and

storms

and now you pay the price

and now your house of cards comes falling

d

o

w

n

and now we take back these stolen teeth

Now we kiss your face like plague

and now you’re here with me, Mr. Flowers

How’s about we root you down here real nice

How’s about we stuff that mouth with food

for your roots

for your petals

pollen

pistil

How’s about we plant you just so, like that

Where the light don’t reach

Where the water seeps slow like

the turn of ages

the drag of death

How’s about you sit right here next to me, Daddy

(now don’t cry sir)

(hush little baby don’t cry)

(don’t make me call for the cut-up girls sir)

(it’s bad enough here with me, don’t you think?)

Flowers don’t cry Daddy

(didn’t you know?)

Flowers don’t cry in the

dank

dark

deep

No

they wilt, they choke

they flatten, sir

and they shrivel up

and die

The Dark Itch

I’m not a nature person. I should say that right up front.

Don’t get me wrong—I appreciate nature. I recognize its importance, and I enjoy that it’s there, looking green and fresh as I stare out the window during algebra class, hating life.

(“Nell? Nell. Aren’t you paying attention?”

Obviously not. “I’m sorry, what was the question?”

Giggles. An aggrieved sigh from my poor, aggrieved teacher. I couldn’t care less what they think. I’ve got a novel in my lap, my index finger marking my spot. The open math textbook on my desk is just a farce, and we all know it.)

Where was I? Oh, yes. Nature, and how I appreciate it well enough.

The thing is that I’ve never much seen the point of going out into nature. All that’s there to find are mud and bugs and dead, rotting things. Is it interesting and pleasingly tidy that said dead, rotting things actually fertilize the ground and help new things to grow? Certainly. Good planning, there.

But I’ve never been the type to go hiking or camping or jumping off piers into lakes. Truth be told, I’m not even a fan of picnics. Why would I want to sit there worrying about ants and bees and inconveniently timed gusts of wind while I’m trying to enjoy my food? It’s just not practical.

And yet . . . well, it’s funny. Not the picnics thing; this other thing.

It’s funny because lately I’ve had this itch to explore the woods behind the school. Not for any particular purpose, at least not as far as I’ve been able to tell, when I’ve stepped back to examine this desire. No, I would simply like to walk about in the trees and see what I can see. I’d like to wander and traipse.

The itch resides in my heart, curled up dark and tight. The itch has a particular feeling to it, when I block out all other thoughts and focus on it. It’s a feeling like being pulled. Like a whisper you have to lean closer to hear. The itch . . . itches. Not like a feather tickling your foot or a stray strand of hair against your cheek.

No, it’s more like an itch from a crusty new scab.

I would like to scratch it.

*

The first time I go into the woods, I’m mostly thinking about how stupid I am. I have my phone, and it’s fully charged, but no one knows I’m here—not that there are many people I could tell. There’s Mom, and Dad, and Mrs. French next door, but that’s about it. Mom doesn’t like to be bothered until she’s had her first cocktail, and Dad doesn’t get home until nine o’clock, and Mrs. French will be too busy watching the news while on the phone with her sister, so here I am, going into the woods with the peculiar feeling that if I disappeared, no one would know for quite some time, and even then, my disappearance would not affect many people.

Perhaps I should feel a bit desolate at this thought, but I don’t. In fact I feel rather exhilarated. I feel something like freedom, I think.

The itch in my chest unfurls.

*

I walk for some time before I find her. The air in the woods is still and cool, which is a nice change from the world of my school. All those children, whispering and laughing, glancing and touching, sweating and stinking.

“All those children”—as if I’m not one of them. Well I am, of course, but none of them read like I do, and I would wager ninety-nine percent of them care about things I do not care about, like school dances and the Top 40 hits and sneaking kisses in stairwells.

I would also wager that none of them feel this itch like I do. They wouldn’t be able to stop talking long enough to hear it, scratching its tiny-legged way into their hearts.

That is what the itch has started to feel like now—now that I’m in the woods, I mean. It feels like a fuzzy, many-legged creature, burrowing its way inside me, digging deeper as if searching for the source of my body heat.

I come to a stop in a clearing of sorts, tangled with undergrowth. Gnats hover in hazy clouds, lit up by the sunlight shifting through the canopy overhead.

I pull aside my shirt and scratch with one fingernail the spot in the center of my chest beneath which the itch stretches and curls. Scratching my chest does not help, but my fingernail leaves behind a stinging red mark, and that seems to please the itch.

The itch grows. It now feels as though it extends from my sternum up into my throat. Not by a lot, simply a tickling tendril, seeking.

And that is when I see her.

She is a girl, perhaps a little older than me, but the sunlight hits her square in the face, and it is impossible to read any lines in her skin that would tell me such things.

She pauses mid-stride, like a grazing deer who thinks she has heard a hunter. Her body is slender, her hair is a pale golden color, and the way she holds her hands and wrists reminds me of a dancer.

The itch in my chest burns. Writhes. Tugs.

I try to say hello, but my mouth is full of weeds. I find myself reaching for the phone in my pocket, and I manage to snap a picture before she turns and runs away—or, that is, it seems as though she must have run away, but I did not see her go. One moment she was there, and the next she was not.

It is only then that I realize the forest is completely still. No wind moves the leaves. The grass is dense and black. I hear no birds or crickets, not even the sounds of traffic speeding down the nearby highway.

It is night. How is it night?

I turn and run, and I do not stop until I reach my home a few blocks away. Mom has fallen asleep in front of the television, and Dad is warming up something in the microwave. I slip upstairs unseen; he probably thinks I am already asleep, like the good, boring girl that I am.

Only when I am in my bed, cocooned in my quilt, do I take my phone from my pocket. I find the picture of the forest girl, and stare at it, hardly breathing.

I am a terrible photographer, it seems. The photo sits there in my hand, unremarkable. The sunlight that had bathed the girl’s ivory skin in a soft wash of gold looks dim, watery. The forest itself is bland, flat. The girl . . . where are her dancers’ wrists? Her arms hang there, awkwardly. Her cloud of hair is not a cloud but a thatch—dry and lusterless.

I press the phone’s screen to my chest, and press, and press. The edges of the phone dig into my skin.

I am a terrible photographer, but then, I was startled, wasn’t I? I was overwhelmed. I have never seen such a beautiful girl in real life, so naturally I wasn’t prepared to photograph her the way she deserves.

I will go back tomorrow, after school. I will return to the same clearing, with its weeds and gnats, and I will wait until she comes back. The girl, that is. She will come back, if the itch in my chest is any indication.

Every time I think of her, the girl, the itch in my chest gives a throb of affirmation. Yes, it says to me. You must go back.

*

The next day, algebra drags on for what feels like eons before the bell rings and we are released into the bright afternoon.

I go to my locker, stuff my things into my backpack, and head for the trees as quickly as I can without looking desperate. It’s not as though anyone could be watching me—no one ever does, for I am not the sort of girl worth looking at. That isn’t me fishing for pity, either; I’m perfectly happy with myself and my life, but I know my place in the world, which is more than most people can say.

Still, you can never be too careful. And besides, I find that I don’t want anyone knowing I am here. The forest girl is my secret, and mine alone. I would like to keep it that way.

As I walk into the forest, the sounds of the outside world fade away—no cars, no birds, no planes overhead. Certainly no laughter or playful screaming from my fellow students in the school parking lot. Here, beneath the trees, there is only the sound of my own heartbeat clogging up my ears.

And the slow, scratchy pulse of the itch below my breastbone.

It seems to me that the woods must be much larger than they appear to be from the outside, for already the bits of sky I can see through the trees is purple and soft. The light that does make it through is dim, bruise-colored. Have I been walking for hours? Before I reach the clearing, I know it is near. I know this because the itch flares up, pulling me onward. It feels like I have eaten something too spicy, and my body is rebelling. For a wild moment, I experience an image of myself, digging my fingers into my own chest, peeling aside the skin and scooping out the itch until the entirety of it wriggles in my palm like a fistful of hairy worms.

When I reach the clearing, she is there. My smile is skin-splitting. It’s only the second time I have seen my forest girl, I know this. And yet it feels like I have been waiting all my life to find her, that this is a moment of long-awaited reunion.

She is even more beautiful today than she was yesterday. Her dress is soft, sheer; the fabric looks as though it would slip through my fingers like water. It reveals things to me that are embarrassing, impossible—long legs and soft curves. I don’t think she’s wearing much beneath that gown, and I can feel myself blush. Her body is so completely unlike my own. Since starting middle school, I have examined myself in the mirror, many times, to try and understand what is happening to my body, why it looks nothing at all like the bodies I see on magazines, in movies. I am stubby and awkward; I have acne, and my hair doesn’t ever seem to sit quite right.

But everything sits right on my forest girl. She ducks her head out of the sun, only slightly. I see the curve of her smile and her wide eyes. She opens her mouth, and out comes a sigh.

The itch inside me darkens, twists.

I fumble with my phone, my hands clammy around it. I try to snap a picture, but my forest girl won’t stop moving. There is something unnatural about her movements—she jerks and darts like a creature would, not as girls do. Come to think of it, there is something unnatural, too, about the slim length of her neck and the shape of her ears.

“Please,” I whisper, stones weighing down my lips, “hold still, for just a second. I just want . . . I just need . . .”

“What will you give me for it?” Her voice cuts through the clearing, the lazy fog of gnats, through me like lightning.

The itch jumps up into my throat. I swear I can feel legs tickling the back of my tongue. Something is inside me, and for the first time I wonder if I should be concerned about that, but then the itch heightens, deepens, blazes.

“For . . . a photo?” My voice is awful, croaking. It isn’t good enough for her, but it is all I have.

My forest girl cocks her head, laughs. Her only answer.

I hold the phone between my cheek and shoulder, rifle through my backpack. Mom gave me a bracelet when I turned thirteen, an elegant charm on a silver chain. It was her grandmother’s, and then her mother’s, and then hers, and now mine. I remove it every day before gym; it is the only pretty thing I own.

I hold it up for her to see; dangling, it turns, catches drops of sunlight and spits them back out. I creep forward, place the bracelet on a snarl of twigs. They’ve choked the dandelions beneath them half to death.

I crouch there, like people do in church. When I glance up at my forest girl, she is smiling, a crescent moon made of teeth. It is, I suppose, an acceptance. I could cry at the sight; she is an angel, and I have made her happy, I think. My bracelet will sit on her dancer’s wrist like liquid moonlight.

Trembling, I raise the phone and snap a photo. When I lower the phone, she is gone—and so is my bracelet.

When I leave the forest, it is night again, and once more I am able to sneak into my room without my parents noticing anything is wrong. Of course they wouldn’t. That morning before I left for school, I switched on my bedside lamp. I wrote a note—Gone to bed early, headache—and taped it on my door and pulled the door to.

I suppose they fell for it. If they even bothered to check the door, that is. We long ago reached an understanding, my tired parents and I. I take care of myself; they work and keep food on the table, and then come home and fall asleep in front of the television. This arrangement suits me well enough. I like being left alone.

In bed, I check my phone, and must wipe sweat from my face before I can see the photo properly. I ran hard back home from the woods; I ran all the way, faster than I thought I could run.

But the photo, this second one—it’s all wrong. It’s even more wrong than the first. I peer closely at it, my heart a thudding weight.

My forest girl’s slender lines are bulbous, twisted. Her hair is the color of dust. Her arms and legs are too long, a disproportionate length that makes the lines of my bedroom shift and seem mutated, like I have been looking at the world all wrong, my whole life, and these lines—my forest girl, deformed and crooked—is what the world is, truly.

Her face is the worst thing—one eye larger than the other, teeth stained and misshapen. She leers, quite frankly. Her gown is a mesh of weeds and dirty cloth, her skin a sick white, drawn tight across her bones like a dirty canvas.

But this isn’t right. I know it isn’t. My forest girl is a wild creature—a doe, a bird. She is beautiful and light-footed. My phone must be defective. Of course. Yes. The lens is dirty. There is a glitch in the programming. I go to my computer, check for updates. I turn the phone on and off. I delete from it everything I can—every app, every stupid selfie I’ve tried to take with my sleeve falling off my shoulder and my lips pursed seductively. You’d think I could figure out how to pose like you’re supposed to, how to make myself look appealing, but whatever the secret is, it eludes me.

I delete photo after photo of myself—lumpy, frizzy, forced—with tears and sweat stinging my eyes.

And yet, still, the photo remains the same: My forest girl, warped. False.

I fall asleep in a tight ball, my phone pressed to my heart, the true image of my forest girl appearing behind my closed eyelids. I keep it there, falling in and out of sleep with the sound of her sigh echoing through my half-dreams.

The itch continues unwinding itself. I feel it skittering down my skin and into my toes. Burrowing there. Waiting.

I kick off the covers and twist, scratching and scratching at my chest until I break skin and blood gathers beneath my fingernails.

*

The next day, I return. Of course I return. My forest girl is a pearl, a diamond, a goddess. I must photograph her as she truly is so that I may carry her with me, always. Who knows if she’ll stay in these woods for much longer? Maybe someday I’ll wake up with a quiet, still heart. An ordinary heart, as I once had. The itch will be gone, and so will she.

But that can’t happen yet, not until I manage my photo. It won’t happen. I forbid it from happening. Others must know, others must see what I have seen. There is a girl in the forest, and she is more beautiful than any of you will ever be, no matter how hard you try, no matter how much make-up you apply, no matter how many designer clothes you buy and prance around in. And she’s not yours. She is mine. She chose me.

She has been waiting for me, I think. When I appear in the clearing, sweating and panting from my mad dash out of school, my forest girl turns to face me. I blink, and she smiles. I blink again, and she is right in front of me, cupping my cheek with a cool hand. My bracelet is a line of light around her wrist. The tips of her nails press into the skin beneath my jaw, and I begin to shake.

I have never felt love before, but this must be it.

Stupidly, I raise my phone. “Can I try again?”

She cocks her head. That same, moon-shaped smile. “What will you give me for it?”

My legs feel ready to collapse. That bracelet was the finest thing I owned. I search the contents of my backpack, and as I do so, my forest girl scrapes her nails across my scalp, sifting through my hair. I wonder what she’s looking for? I almost laugh, and then, with the next breath, I feel ready to start crying. Textbooks, spiral notebooks, change from lunch.

My pocketknife. Dad gave it to me when I started walking to school. “To defend yourself,” he said to me, “in case you should need to.” Then he ruffled my hair and went on his way. The microwave beeped, his leftovers ready and steaming.

I flip open the pocketknife and stare at the blade. I have never used it before; when Dad gave it to me, I rolled my eyes and tossed it into my backpack and forgot about it. We’re not supposed to bring knives to school, but it’s a small school, and I’m a no one, and so who cares, really? No one would think to search. No one would think to search me for anything.

Except for my forest girl. She continues combing my hair with her fingers, her nails dragging trails across my skin. What is she looking for? Will she find it? Whatever it is, I hope I have it.

The itch inside me darkens, a black bloom spreading through my lungs. My chest is on fire; my lungs are twin nests of bees, buzzing.

My forest girl stares down at me, tips up my chin. Her eyes are dark as the night above; it is night, and she is waiting. I have never seen anything so beautiful as the pitch pools of her eyes, waiting.

I am alive. I am awake.

I drag the blade across my palm. As soon as I am finished, my forest girl grabs my wrist, yanks it toward her mouth. She laps up every drop of blood, her teeth grazing my fingers, and when she has finished, and I stand there, cold and dizzy, I snap a picture, even though there is no light, and I can’t possibly have gotten a decent image.

“Did you find it?” I whisper to my forest girl, but she has left me, and the trees around me are made of ink and shadows.

Back home, my parents are laughing in front of the television—sitting side by side, miraculously. I pretend that I have come down from my bedroom for a drink of water, mumble something sleepy at them, return their I love you sweeties with I love you toos.

Upstairs, in my bed, I drop my phone three times before I manage to open my photo library. I nearly drop it again when I see my forest girl staring back at me from the latest photo—a grinning, pale wraith. She is made of sharp lines and swollen limbs. Her teeth are sharp, her eyes are all black—no whites around the edges. Her ears are too long and too sharp, jutting up from her head like a bat’s might.

Her jagged smile mocks me. I throw the phone across the room. “That’s not her!” I try to yell, but it comes out a harsh whisper. “You’re a liar, you’re lying!”

The phone hits the wall and bounces to the floor. I crawl to it, not caring when the carpet’s fibers make my palm sting. Frantic, I pick up the phone, check it over. No cracks; nothing shattered. The photo remains, this perverted echo of my girl, my beautiful girl.

I drag myself back into bed and cradle the phone in my hands like a baby. I do not sleep—I know this, I remember how long the night felt, how many hours I lay there, sweating, nearly hyperventilating, digging the heels of my palms into my eyes so that maybe I would stop thinking about her, how beautiful she looked in that still clearing where the only sound is her breathing and my breathing and the ever-present hum of buzzing gnats—I remember all of this.

But when I wake up in the morning, my sheets are stained with blood from the patchwork of scratches across my chest. Red marks from my own clawing fingernails.

The itch snakes through me, still—heart to limbs, heart to belly, heart to tongue—like a spider with its pincers in my gut.

*

I don’t go to school the next day. Are you kidding me? What’s the point? There is no point, not to anything but her.

The itch tells me so, and I agree.

Instead I wait until first Dad and then Mom leaves for work, and then I raid everything—their dressers, Dad’s armoire, Mom’s nightstand, her jewelry cabinet. I grab bundles of cash, diamond earrings, Grandpop’s pocketwatch, my great-aunt Willa’s rosary. Everything pretty, everything that glitters.

None of it is good enough for her, but it will have to do. I will get a photo of her, to keep with me always. I will get it if it takes all day, and all night. All the days, all the nights. I will get it if it requires I offer her everything I own, everything my parents own. One photo for each shining, polished piece. One photo for each crisp, folded twenty.

Before I leave the house, I go to the bathroom to find fresh bandages for my chest—and then stop, and change my mind, leaving them open and raw. I change into a tanktop so my forest girl will see them better.

They might please her.

I open and close my palm, making the cut sting and weep. With each clench of my fist, the itch beneath my skin pulses.

Perhaps it’s just my excitement talking, but I think that the itch, whatever it is, is ready to come out.

*

When I reach the clearing, I am lightheaded, my mouth dry. I should have brought water on such a hot day, and who knows how much blood I lost—was it only yesterday?

My forest girl waits, perched on a stone, looking bored. When I enter the clearing, she straightens and smiles. She opens her white arms wide, welcoming me.

Grinning, giddy, I dump everything in my backpack onto the forest floor—every last dollar, every last jewel—and step back, pleased with myself.

My forest girl rises from her perch like a queen, her gown trailing the dirt behind her. She inspects my offering, sniffs, glares up at me.

I hold up my phone, hopefully. “I only want a photo of you,” I whisper.

She stares at me, waiting.

I hesitate. “It’s because you’re so beautiful. I can’t stop thinking about you.”

One corner of her mouth curls up into a smile. She approaches, wraps me into an embrace that feels like one of those dreams when you can simply push off the ground and fly. “Me?”

Surrounded by her touch, I understand how miserable my gifts are, how inadequate. I flush and gulp down tears. “I’m sorry. It’s all I have.”

My forest girl kicks the gifts aside. The pile of trinkets topples, scatters. “I don’t want them,” she whispers against my ear.

“But it’s all I have!” I am sobbing now, like a little kid with no self-control. I try to hide my face from her; I look terrible when I cry, swollen and splotchy.

“Not true,” my forest girl says, her voice teasing me.

I quiet, grow still. The itch inside me builds and builds, and I realize with this light feeling—a puff of air, a flood of warmth, a sigh—that the itch is not something trying to get out.

It’s something trying to get in.

And the scent of my itch, the feel of it, the taste of it, tickling my tongue—it’s her.

“Me?” I gaze up at her, and I can feel my face morphing into what is no doubt the soppiest, most ridiculous smile there has ever been, but I don’t care, for now I understand, and the itch inside me becomes the sun, burning bright and steady. “You want me?”

“Only you,” purrs my forest girl, tracing the lines of my face with one sharp fingernail. “But you have to say it. You must tell me you’ll do it. You must—”

“Take me,” I blurt out, eager and stupid, grinning and beaming and ready to come apart from happiness. “You can have me.”

Her eyes glitter, shift. She holds out one finger, warning me, teasing me. “Just one photo,” she reminds me.

“And it will really be you this time, in the photo?”

“My true self,” answers my forest girl, her voice a fall of rain, and it is mine, she is mine, she is all for me.

I nod, fumbling with the phone, and as soon as I snap it, as soon as I press the button and lower the phone, the itch inside me bursts.

I fall to the ground, blinded by darkness, choked by it, burned by it. My skin is on fire, it is made of bugs—swarming, pinching. I crawl through it, scratching myself, clawing at myself, and when it is over, I feel that the itch is now a chain, wrapped around my heart, wrapped around my wrists, my ankles, pinning me—pinning me to her.

She yanks me up into her arms, and her skin is cool, still. It soothes me, and I think I may be drunk. I have never been drunk before, but you hear things, you know, in a school full of deviants.

“Try to run,” she hisses against my cheek, “and you’ll feel much, much worse than that.”

Run? I would never run. Not from her. I think that, my thoughts slow and muddy, even as I look up and realize that my forest girl is gone, and it is a creature now dragging me across the mud, toward a fat tree with an opening at its roots. Its claws dig into the soft skin of my upper arm. With each tug across the dirt, the itch through my blood tightens—her chain, woven through me. She grins, her mouth full of fangs. She rips me to my feet with one fierce yank of her arm, and the itch stabs my chest; the chain tightens.

“See?” she growls, her misshapen face hovering over mine. Her pointed ears. The sharp lines of her face. She is not a creature of my world, and I love her for it. There is a part of me that screams how wrong this is, how in danger I am, how she is evil, how I do not love her. She tricked me, she tricked you!

But I am well aware this part of me will soon die. Even now, the itch wraps around that frantic voice, choking away its air.

“Mine now,” she tells me, and I nod, letting myself be dragged across the tree roots into darkness.

“Yours,” I whisper, and the bark tears at my flesh, and we are below, now, in her world, where it is all darkness and unnatural heat, and the shadows shudder and laugh, and the only thing I know is her arms around me and the itch wrapping its coils around me, darkening, darkening—

*

“Do you think she ran away?”

I roll my eyes. “Where would she go? And with what money?”

“Maybe she stole her parents’ credit cards or something.”

I roll my eyes again. There’s a lot of eye-rolling whenever Darren Wyatt’s around, but I’m not the kind of person to chicken out on a dare, so I’ll have to put up with him. “Maybe.”

“Or maybe she’s still hiding somewhere, trying to freak everyone out.” Darren snorts. “Maybe she’s, like, spying on us all, watching the town go crazy looking for her—”

“Just stop talking, okay? You’re annoying the crap out of me.” Which is true. But more than that, talking about Nell while we’re searching the woods—the same woods into which Mr. Elliott saw her disappear the day before last, while we were all stuck in first period—just seems . . . I don’t know, like bad luck. Speaking ill of the dead and all that. Not that Nell is dead. She could be, obviously, but no one’s saying that out loud yet. At least not around us kids.

Darren mutters something at me, but he can insult me all he likes, as long as we just get in and out of here as quickly as possible. I’ve done stuff before—broken into cars, shoplifted, the usual. Petty stuff. I’ve even gone into these woods before, when Darren and I tried the cigarettes he stole from his mom’s purse.

But the woods are different now. I’m sure it’s just the knowledge of Nell’s disappearance playing tricks on my brain, but still. I don’t want to stay in here any longer than I have to. I hope we find something soon, or at least come up with something we can take back to the guys, something to scare them and start a nice, juicy story.

It’s like the trees were listening to me, because maybe thirty seconds after I think that—I hope we find something soon—I see it: A rectangle of turquoise, lying in the dirt.

I pick it up, and Darren looks over my shoulder. “Dude. Nell’s phone? Do you think?”

“Maybe.” I turn it over, press the home button. I slide my finger across the screen to unlock it, and it doesn’t ask me for a passcode, so the photo shows up immediately.

Darren curses and jumps back. I fling the phone away, and it flies into the dirt.

We stand there, breathing hard.

“What was that?” Darren asks, and when I head for the phone, he grabs my arm, squeezes tight. “Josh. Don’t, man. Evidence, right? That’s some freaky . . . don’t, okay? Leave it.”

But I can’t help it. I have to see it again. I pick up the phone, touching as little of it as I can. I turn it over, and there it is—the monster, staring at me from the last photo Nell took. It’s pale and has long, pointed ears. Its mouth is wide, huge, fanged; its body is all wrong, long lines and sharp bends and swollen joints and what looks like infected cuts.

As I look at the photo, it feels like something crawls into my chest, sliding into it like a worm. It stays there, sticky and fat, like I’ve eaten too much, like I’ve eaten something bad.

There’s a sound, behind me—Darren, running away. “Forget this, man!”

And another sound, in front of me. A flash of white.

I whirl. I think, for a minute, that I see a girl—barely dressed, delicate, beautiful. My chest twists, and my body moves, like it’s ready to run after her. I breathe, I blink, and she’s gone.

Was she there at all?

I tuck Nell’s phone in my pocket and turn to head home. Out of nowhere, the thought comes to me that I should come back. Not today. Maybe not even tomorrow. But someday. Someday soon, I think. I’m distracted by a million different things, but I definitely should. Come back, that is.

Something must have bitten me. A mosquito, maybe. There’s an itch on my chest, and I scratch it, and call after Darren. “Darren? Come on, dude, don’t be such a baby. Seriously? There’s nothing here but trees.”

The Library of Dreams

At the Library of Dreams, you can conveniently deposit your unwanted nighttime imaginings for the low, low price of twenty-five dollars.

A Librarian will collect, archive, and catalog your dream, but don’t worry—you don’t have to wait around during the boring stuff. As soon as your dream has been safely withdrawn, the Librarian assigned to you will give you a receipt—hold on to this, mind you—and you can be on your merry way.

Now, let’s say you find yourself wanting to re-live your dream—whether that’s because it was a particularly thrilling one, but rather too thrilling to reside permanently in your mind; or because you are thirsty for inspiration and think it could make for a rollicking good story, if only you could remember what it was. Or perhaps you want your dream returned to you altogether, because, on second thought, it unnerves you to think about some figment of your subconscious sitting unused in a drawer somewhere. Well, you’re in luck: Recollection and restoration services are available, with pricing upon request. All you have to do is present your receipt (did you hold on it as you were supposed to?) at the Welcome Desk, and a Librarian will assist you.

Dream harvesting and storage, and excellent, first-class service, all for only twenty-five dollars.

Isn’t it a bargain, though?

But wait! There’s more!

If you will allow your dream to be a matter of public record—that is, freely available for viewing by any registered citizen—we will waive your collection fee, and pay you a sum of one hundred dollars (plus an additional percentage of each viewing). Think of it: Countless others, generations of others, paying to experience your own dreams, long after you’re dead and gone.

Kind of exciting, isn’t it?

Here at the Library of Dreams, we certainly think so.

*

It was Taja’s first time working the Welcome Desk at the Library of Dreams, and she was nervous about it, but not in the way you might think. She wasn’t nervous because she was the youngest apprentice at the library and was therefore bound to screw up something.

No, she was nervous because, since coming to work at the Library, she’d been content to scuttle around in the shadows and run errands and make coffee for the Librarians, even Madam Jacosa, who was by all possible definitions terrible. Taja had let the Librarians with bad attitudes yell at her and the Librarians with workaholic tendencies ignore her. Basically she’d allowed herself to drift unseen and (mostly) unloved through the Library like the bottom-ranking piece of scum she was, with no complaints.

Even though she was more talented than all of them.

Especially because she was more talented than all of them.

But now, thanks to a scheduling error, and hopelessly flaky Elis having called in sick again, Taja had been hastily reassigned to the Welcome Desk for the day. And at the Welcome Desk, she’d have no choice but to be noticed. And Taja worked very hard not to be noticed.

It was for the good of everyone, really.

The front door dinged and a rather furtive-looking young woman entered, half-hidden by a felt hat and tasseled scarf.

“Welcome to the Library of Dreams,” Taja said. “How may I help you today?”

“Yes, hello.” The woman hunched over the desk, as if protecting her words. She glanced at the five doors marked HARVESTING, RECOLLECTION, RESTORATION, VIEWING, and WAITING. “The thing is, I’ve never been here before.”

Obviously. “You don’t say?” Taja said.

“It’s just I’ve always thought dreams shouldn’t be tampered with, and that the Librarians have far too much power, and that something else is going on here. Something nefarious. Behind the scenes, as it were.” The woman eyed Taja expectantly.

Taja kept her face serene. Another conspiracy theorist. The Library saw at least five a day. “I’m sorry to disappoint you, but I can assure you, we’re far from nefarious here at the Library of Dreams. We’re simply providing a service.”

“I read there was once this king who thought the Library was evil, that it should never have been built. He tried to burn it down, and then he disappeared.” The woman leaned closer. “Under rather mysterious circumstances.”

“Yes,” Taja said calmly, “I’m familiar with the story. Roysius the Third. He was quite mad.”

The woman’s mouth thinned. “You look rather young to be working here. I’m not sure I feel comfortable talking to you. Where’s your supervisor?”

“I’m thirteen, and quite capable, I assure you. My supervisor is Larkin, and he’s busy just now.”

“Oh yes? Busy doing what, exactly?”

Taja’s smile dazzled. “I can’t tell you that. Official Library business.”

The woman scowled, turned away, tapped her foot against the polished marble floor, and turned back. “Fine. Fine.” Then she mumbled something. Taja pretended she hadn’t understood.

“What’s that?” she asked sweetly.

“I said, I would like to view a particular dream. Should be filed under Halon, of the Dower family. He’s my . . .” The woman rolled her eyes. “All right, so he was my boyfriend. I know it’s silly, but . . . Right before he left me, he had this dream. I don’t know what it was about, but it upset him so much he could hardly speak, and then he left me, and I have to know what it is, I just have to. The cousin of his roommate is a friend of my sister’s, and she said he came to the Library the morning after he had that dream, which means it must be filed away here somewhere, and I’m fairly certain it’s public. So . . . I’d like to look at it now. Please.”

Taja waited with her hands clasped on the table before her. “I really didn’t need to know all of that. I just needed to know the service you required.”

The woman gaped, flushing. “And you just let me go on and on?”

“I didn’t want to be rude. Now,” said Taja, and here was where her heart’s steady trot became a gallop, “please let me see your registration, and I’ll get things started.”

The woman fumbled in her purse, muttering to herself. Then she slid her registration card across the desk. When Taja took it, she made sure her fingers grazed the woman’s hand.

All Librarians could see dreams. It only required a slight touch of skin to skin for the dreams to appear, surrounding the dreamer—ghostly shapes, cityscapes, nonsense. The dreamer, flying. The dreamer, falling. The dreamer, outrunning a forest of tornados. Typical stuff, most of the time. Same song, different voice. Recent dreams appeared closer, more vivid. Long-ago dreams were harder to make out and farther away. Sifting through the images to find the long-ago dreams was like fumbling through a dimly lit mirror maze with thousands of people, trying to find what you needed—one particular reflection among millions.

But for Taja, it was different.

*

For Taja, a touch didn’t mean simply seeing dreams. It meant seeing everything—dreams, memories, wants, fears. Stray violent thoughts. Deepest secrets.

It was a gift, Taja’s mother had said. At first.

Then Taja started telling her mother what she saw every time they kissed and hugged, every time they joined hands and danced in the kitchen while breakfast cooked: What her mother feared. What her mother wanted. What her mother thought of old man Duggan from next door. Where her mother had kissed the banker she’d gone to dinner with the night before. How her mother had hated Taja for a time when Taja was very small.

How her mother had thought of hurting her.

Taja didn’t hold a grudge; she’d long ago learned enough about the way minds worked to know that you couldn’t always control what you thought about. Accepting that was a matter of maintaining sanity, for Taja. She wasn’t insulted or anything.

But, quickly, the reality of this became too much for Taja’s mother. “What am I thinking now?” she would ask nastily, when Taja hugged her good-bye before school. “Tell me what I’m thinking,” she said one night, suddenly, while preparing supper. She grabbed Taja by the throat in a fit of mad-eyed rage, shook her, and then released her.

She watched Taja fearfully from across the room while they watched evening programs on the television. “I’m sorry,” she would sometimes whisper, and Taja would pretend she didn’t hear.

Taja’s mother started flinching, cursing, sobbing every time Taja entered a room, every time she moved or spoke, every moment she existed. Once, she threw a knife at Taja when she came down to the kitchen to help make lunch. “Don’t touch me!” Taja’s mother screamed, and Taja calmly left the room and went to the park to play with whatever kids she could find, because all of them were much happier than she was, and when she bumped into them while playing games, she saw flashes of smiling parents, and birthday parties full of color, and bright, brilliant futures so unlike the one she saw for herself.

Then, one night, Taja awoke to find someone—a gloved, masked someone—dragging her from her bed, stuffing her in a sack. She knew it was her mother because she smelled her rose perfume. In the back seat of the car, she sat silent and blinded. Through the cloth sack’s weave, she saw the faint shape of her mother, driving. Before Taja’s mother threw her over the bridge into the river, Taja’s mother whispered that she would be happier now, without Taja around.

“You monster,” Taja’s mother hissed, her voice choked with tears.

That was the moment, right before she slammed into the icy water, that Taja decided her mother wasn’t worth her time, and that her ability was a gift, not a curse. It was special; it could probably prove useful somewhere. So Taja decided she would live, and find out where that place might be.

*

“If you don’t mind,” the woman snapped, whipping her hand away from Taja’s, “I’d like only my assigned, grown-up Librarian to touch me.”

“I’m sorry! Sorry. It was a mistake. I— ” Taja paused, collected herself, stared at her desk. “If you’ll please take a seat in the Waiting Room, a Librarian will be along shortly to assist you.”

The woman gave Taja a curt nod and hurried to the Waiting Room. Her heels clacked against the floor like teeth.

Breathless, Taja slid the woman’s ten and two twenties into the cash drawer and dropped the woman’s registration card into the holding file for safekeeping. The truth was, though, that she wasn’t sorry at all. Stealing thoughts like this sustained her. She craved the thoughts of other people more than she craved actual food.

She was no curse. She was a gift.

I am a gift, mother. And I am alive.

What had Taja seen this time? She blew out a slow breath, assessing. An array of images had laid out before her, for that miraculous second. A vastness of books opened to their most vivid illustrations:

The woman customer, kissing a man. The woman, crying in a dimly lit room. The woman, winning the Presidential Award for Notable Contributions to Science. The woman, working in a laboratory. The woman, laughing in a theater with her friends. The woman, kissing a man, kissing a man, kissing a man named Halon Dower. The ex-boyfriend. This woman woman was absolutely miserable about him. Taja couldn’t feel her misery, but she could clearly see it in how many thoughts and memories focused on him.

This, of course, made Taja think of Larkin.

If anyone else existed who could do what Taja could do, and happened to touch Taja at that moment, her thoughts would have appeared to that person like images on a television, and they would have looked something like this:

Larkin, pulling Taja out of the river, exclaiming that she couldn’t be dead, please, not this poor little child.

Larkin, nursing Taja back to health in a tiny, warm room lined with books.

Larkin, giving Taja her blue apprentice’s coat.

Larkin, smiling. Chuffing her shoulder. Ruffling her hair. Looking at her. Singing while he worked.

Larkin, Larkin, Larkin.

Larkin, kissing her. Someday, when she was older, taller, beautiful. He would not ruffle her hair then.

(Her most precious, secret hope.)

The door opened. A man walked in, suited, vested, wearing a dark bowler hat. His suit had long coattails. Taja approved of this, and of his clean, attractive jaw.

“Welcome to the Library of Dreams,” Taja recited. “How may I help you today?”

“I’m here for a recollection,” the man said, sliding a crisp fifty and his card across the counter.

Taja appreciated regulars, and also people with voices coarse and rich, like this man’s. Velvet-textured. Rough around the edges.

“If you’ll please take a seat in the Waiting Room— ”

At that moment, Taja touched the man’s wrist. There was a strip of skin there, between his glove and his sleeve. She hadn’t meant to; she generally tried to limit herself to one touch a day. But she had been distracted by this man’s soft-crackling voice, by her lingering thoughts of Larkin, by a stray memory of her mother.

And so she had touched him. And so she had seen . . .

The city, burning. Her city.

The presidential palace, overrun with crawling shapes. Child-shaped hunters with claws like needles. Winged and scaled, slippery and tough-hided. Gaping jaws and dead eyes and no eyes, jagged beaks and glistening hooves, and—

Smoke and screams, pale wings in the air, fluttering and leathery—

Blood in the streets, a woman tearing at her hair; fat, wet shapes plopping onto rooftops, burning holes through the shingles—

“Is something wrong?”

Taja’s head snapped up. The man was watching her with mild curiosity, his eyes clear and steady.

“No, I— I’m sorry,” Taja stammered. “It’s my . . . it’s my first day.”

“Oh. How exciting for you, I’ll bet.”

Something like that. Oh gods, oh gods. What had she seen? “What is your name, please?”

“It’s on the card, isn’t it?” The man’s smile was a tiny ghost of a thing. “But all the same, it’s Winters. Soren Winters.”

Taja’s fingers shook on the typewriter keys. She was punching in absolute nonsense. Not that it mattered. Even though the name he provided matched the name on his registration card, she had seen the truth in his mind—this was not his true name. He was lying, about that and other things she couldn’t interpret.

“And you’re here for a recollection,” she said, in a casual sing-song. “Sure, sure.”

“Shall I go to the Waiting Room?” Mr. Winters took off his hat, smoothed his hair. It was the color of dust, and impeccable.

“No!”

Mr. Winters turned, his eyebrows tiny twin question marks. Not surprise so much as Oh?

“No, no, no, not today,” Taja said, hurrying to him with a clipboard in hand, which she hoped made her look at least halfway legitimate. She had no idea what she was doing, but she could not let him go through recollection. “We’re so dead today. I can take you right in.”

Dead. So completely, screamingly dead, like the city in Mr. Winters’s mind.

It hadn’t been a dream, that image. It had been a want. A someday. A desire sharp as hunger and as certain as now—the sensation of this is happening.

Even more certain to Taja was the knowledge that “Mr. Winters” wasn’t just here to recollect a dream.

He was here to steal one.

*

As far as Mr. Winters knew, Taja was just a Librarian—or most likely an apprentice, judging by her youth—which meant she couldn’t see anything but dreams, and so he had no reason to worry. He had long ago learned how to control his dreams, and had been careful never to dream of . . . particular things.

This girl Taja was a little odd, true, but then, she was thirteen, so what did you expect?

He laughed, once, softly. Thirteen. That had been a good year.

Not for his father, true. But for him, at least.

And soon, all the quiet years between then and now would prove to have been worth it.

*

Taja led Mr. Winters through the RECOLLECTIONS door and down a series of hallways she was definitely not supposed to be in, ever. Were it not for Larkin, she wouldn’t even know they existed.

“And these are our recollection rooms,” Taja explained, gesturing pointlessly to the dark wooden doors lining this stretch of hallway. The carpet was thick and blood-red. Taja remembered the streets of Mr. Winters’s mind, stained with dead bodies, and felt faintly ill. “You’ll be assigned to one of these, and your Librarian will meet you there. It doesn’t hurt much, despite what people say. Recollection, I mean.”

“I’m familiar with the process. I’ve been here before, remember?”

Taja didn’t look at Mr. Winters, but she heard the hardly-there smile in his voice. “Oh. Right. Sorry, just—”

“It’s your first day.”

“Right.”

Think, Taja, think! But honestly, what was there to do? If she told anyone what she knew, they’d demand how she knew it. If she explained how she knew it, then her secret would no longer be a secret, and who knew what would happen to her then? The more skilled Librarians tended to disappear—it had happened twice during Taja’s years at the Library, once with Phenna Talisin, and then, later, with Garet Azhar, both of whom had just up and vanished one day, at the height of their popularity with patrons. The scandal had monopolized the papers for weeks, and the Library had enjoyed a temporary and not insignificant bump in business.

No one could resist a mystery, especially a grisly one.

Taja had often feared that she would wake up to find Larkin gone from her in this fashion. Everyone knew he was a genius. They called him Dreamkeeper, and whenever they did, he rolled his eyes and said something like, “They make me sound so old. Am I that old, Taja, to be given such a name?”

Once, Taja answered that no, he was not old, he was beautiful, and her cheeks had burned, but she would have said it a hundred more times if she could have, and Larkin had looked at her for a very long time before brushing the hair out of her face.

If she ever woke up to find him gone, she would tear apart the Library until she found him.

Would Taja, should she be found out, disappear? And if she did, would Larkin come looking for her?

“Do you think we’ll keep walking for much longer?” Mr. Winters asked, adjusting his coat. “Or do you have a special room in mind?”

Taja felt suspended in mid-air for an instant, and then nearly fell over her own feet. A special room. Of course. A plan slammed into her like the punch of the icy river water, straight to her lungs. It was wild, it was impossible. It was most likely fatal. But it was the only thing to do.

Mr. Winters could not be permitted to recollect someone else’s dream and steal from the Library. He could not be permitted to leave the Library, either, not with such plans churning in his head, and not on Taja’s watch. The Library had raised her. She had grown up in these unending hallways, ordered here and there by tired, frazzled adults in dusty robes, their eyes bloodshot from too much dreaming. She was to be a Librarian someday, and Librarians did not fear death.

Taja had faced death before, and lived.

“Not much longer,” she said cheerfully. “Sorry for the walk. They’ve been doing work on the front rooms.”

A special room, indeed. She would take him to the most special room of all. She would take him to the Vault of Nightmares.

And she would lock him inside.

*

Larkin probably didn’t even remember that he had told her. But he had.

It had been that first night, when Taja was six and shivering in Larkin’s arms, river-drenched to the bone. He held her close to the fire and spooned hot broth into her mouth. He sang to her, a lullaby called “The Fairies of Far Westing,” which reminded Taja of her mother and made her gasp with pain.

To soothe her, Larkin had shown her the marvelous things in his office: The rows of books cataloging some of his own, most beloved dreams. The wood-handled silver bell that had been a gift from his father.

And the belt of keys kept in a small drawer, which could only be opened by pressing the wood carvings on the drawer’s face—curling vines and singing birds, a rose with twenty-three petals—in a particular way.

The white key was for the Office of the Head Librarian, upstairs in the Tower.

The red key was for the Fifth Floor Collections, of which Larkin was in charge.

The black key was for the Vault of Nightmares.

The tiny brass key he gave to Taja, and which she wore always on a silk ribbon, hidden beneath her shirt, was her own key to his office. “If you should ever need a safe place to hide,” he had told her, not long after her arrival, “you are always welcome in here with me.” She had taken him up on that, often curling up in the threadbare chair in the corner to study, just to be near him as he worked, just to smell the ink staining his fingers.

He probably hadn’t thought Taja would remember anything about those keys. He certainly couldn’t have imagined that, every time she touched him, she searched his mind for an image of how to open the drawer of keys, until she had the combination memorized.

But Taja remembered.

*

Taja withdrew her brass key and opened Larkin’s office.

“If you’ll just wait right here,” she said to Mr. Winters.

He nodded, once, and said nothing.

Taja slipped inside the office, shivering. It was obvious Mr. Winters was becoming suspicious. She couldn’t blame him. She had kept him walking for fifteen minutes, and they were nearing the bowels of the Library, where everything was icy cold and the walls were stone instead of paneled wood. Mr. Winters had to have realized by now that this was not standard protocol.

And yet he was not protesting, or demanding to be taken back upstairs. Perhaps he was curious.

She hoped that was all it was.

Taja pressed the wood carvings, in the right order—fifth petal from the right, bluebird, bell, third petal from the top, and so on. She kept her ear pressed to the wood; with each press of her fingers, a tiny click sounded. The drawer popped open. She pulled out the black key and almost dropped it. It crawled. The surface of the key was cold, and wriggled as if from the cycling movement of a thousand tiny legs.

Repulsed, Taja dropped the key in her pocket and grabbed a random stack of papers from Larkin’s desk. The movement jarred a scarf lying there; it slid to the floor, and Taja caught the scent of Larkin—cinnamon (his favorite candies) and smoke (from the fires on this level, which were always lit to keep the Librarians from freezing).

I’ll come back, and I’ll tell you how much I love you, I won’t waste another second, she thought, and left.

“Almost there,” she said brightly to Mr. Winters, locking Larkin’s office behind her. She was surprised to realize she felt no urge to cry at the thought that, if something went wrong with her plan, she would never see Larkin again. She supposed she was too terrified to cry, as she had been on the night her mother had tried to kill her.

“What was all that about?” asked Mr. Winters.

“Just needed some paperwork.” Taja waved the papers with far too much enthusiasm.

“Ah. I see.” Mr. Winters moved his head the barest inch, his eyes looking to the ground, as though he were listening for something. His tongue flicked out, wet his lips.

Taja turned away, though every instinct she had screamed at her not to turn her back to him. There was something abhorrently serene about him.

The weight of the key in her pocket was like a living thing. Cold, and shifting.

*

The Vault—a nondescript door of weathered wood on the lowest level of the Library, which Taja only knew about through years of touching Larkin whenever she could get away with it. Apprentices were not allowed here; few Librarians were allowed here. The air here was so cold that Taja’s breath came in puffs. The weight of the Library above them pressed on her shoulders.

“How very odd, this place you’ve brought me,” Mr. Winters remarked, his eyes fixed on the door. He seemed different now, the lines of his body sharper, longer. Alert.

“My supervisor told me that, as one of our regular patrons, you get the special treatment this visit,” Taja said, her fingers shaking as she tried to fit the black key into its lock. “It’s like a sort of contest, you see, and you’re the winner.” The key twitched in her hand. Something bit her.

The lock turned, and the door opened. Beyond it, Taja could see only darkness. Right, then. There was no turning back now. Larkin, Larkin.

“Please follow me,” said Taja, stepping just inside. “Your Librarian will be right with you.”

Mr. Winters clasped his hands behind his back and followed her in. Then, Taja froze, considering. The pieces of herself shifted and realigned. She stood there for an instant, for a slow hour. What was she doing? What was she thinking? Her blood was a dull, desperate roar.

She could have stepped outside, slammed the door shut, and locked Mr. Winters inside. That had been the plan. A good plan. A plan to be proud of. But instead Taja flung the key back into the hallway and slammed the door shut, locking them both inside. Something had seized her heart and rooted her here, in this darkness, behind the weathered door.

Something like craving.

She had seen people’s nightmares before, in brief flashes that kept her up for long, sleepless hours—not from fear, but from fascination. Beasts and devils, gods and death. What would a whole vault of them look like? Were any of them, she wondered, as monstrous as she? She would look, only for a moment. And then she would open the door and sneak out before Mr. Winters had even begun to process where he now found himself.

“My curious girl,” Larkin had once called her, his arm loosely about Taja’s shoulders as they sat by the fire. Taja had not been able to stop staring at his long legs, his dear, shabby shoes. “Your mind is a diamond. You’ll make a fine Librarian someday. Even finer than me.”

“Impossible,” Taja had declared hotly. “No one could be finer than you.”

And Larkin had kissed her on the cheek. “Little sister,” he had said, “it’s as if we share a heart.”

My curious girl.

Taja stepped away from the door, hungering.

*

The Vault was completely lightless—or at least it seemed so, at first. Taja’s breath came thin and fast. Though it had been cold just outside the Vault, inside the air was tropical. Damp, oppressively thick. When Taja’s eyes adjusted, she saw a rocky cavern, tremendous, never-ending and many-roomed. Fires here and there, and piles of luminscent moss, gave everything an eerie glow. The ceiling disappeared into blackness. There was water, somewhere; Taja heard the rush of a current.

The air smelled like burning.

A massive explosion to her right knocked Taja off her feet. She tumbled down the moss-covered ridge and hit her head. Dazed, she looked back up the ridge. The Vault door had disappeared, as had the wall surrounding it. There was only more cavern—fires dotting sky-high cliffs, figures crossing distant bridges. A black lake. A dim blue city.

“Mr. Winters?” Taja tried to call out, but her ears were ringing, and her voice came out strangled.

“What the—? Taja? Larkin’s girl?”

A voice behind Taja made her turn. Her head throbbed, and she nearly threw up. A woman stood there, scarred and sweating, her short hair in spiky braids. She wore thick goggles and carried a gun that crackled with white lightning. On her frayed shirt was a faded, familiar insignia—that of a Librarian.

Taja squinted at the woman’s face; it was spattered with blood, but Taja never forgot the face of someone whose mind she had touched.

“Phenna?” she breathed. “Phenna Talisin? But you’re dead. You disappeared. Everyone was looking for you—”

“Not dead. Not yet.” Phenna yanked Taja to her feet. “Get behind me, and cover your eyes.”

Taja did as she was told, peeking up through her fingers at the top of the ridge, where . . . something . . . was moving. Pale and thin, unthinkably tall, the something unfurled its wings, tearing itself free from what remained of a fine suit and vest, a shell of human skin. It blew out a breath, so hot Taja’s eyes watered. A charred scrap of bowler hat fluttered to her feet.

“All I wanted today was that key,” the thing rasped, in a voice that was part Mr. Winters and part wrath, part fever, part crumble and flay. As it spoke, its words dissolved until they were hardly intelligible, as if he were, right in front of them, forgetting how to form human speech. “But you, child, have given me something even better. You . . . have brought me home. And now, we can begin.”

The thing that had been Mr. Winters reared up to its full height, stretching its wings out twenty feet on either side. Its eyeless face turned to the black sky, and it shrieked to rend apart the world.

Throughout the vast cavern, screams echoed back, followed by two distant explosions.

“Fantastic,” Phenna muttered, cocking her gun. It began to whine, humming higher and higher. “You couldn’t have brought one of the little ones, could you, girl?”

Taja clutched Phenna’s waist, pressing her face against Phenna’s back. “What’s going on?” she screamed over the din.

“War, that’s what,” Phenna spat, “and you’ve just brought the other side a great bloody bomb.”

A low boom above them—the thing that had been Mr. Winters beat its wings once, twice, and rose up to hover, extending its claws. Its tail was a fat whip; Phenna ducked down to avoid it, bringing Taja with her. The thing that had been Mr. Winters shrieked, wheeled about. Its mouth reeked of blood and writhed with worms.

In the flash of time before the world ended, Taja could think of only one thing: The broken-hearted woman, sitting upstairs in the Waiting Room, pining over Halon Dower. The Library? Nefarious? No, madam, you’re mistaken. Sorry to disappoint you. We’re simply providing a service.

Taja burst out laughing. Conspiracy theorists, indeed! Gods bless them all.

The thing that had been Mr. Winters lunged at them. Phenna cursed, raised her gun to her shoulder, and fired.

Unwrapping February

When most people think of February, they likely think about love, or Leap Day, or how unforgivably cold the weather is that time of year, and will we ever feel warmth again? Ever?

(Ahem. Pardon me. I’m afraid your Curators are getting a touch of winter madness about them. Even living in a house the size of the Cabinet does not make one immune to the torments of cabin fever.)

Here at the Cabinet–at least this year–February is about GIFTS.

They might be gifts of love . . . or of hate.

They might be ribboned gifts left on your doorstep . . . containing dark secrets instead of dark chocolate.

They might be whispered secrets wrapped in lies or shiny trinkets lined with terrible curses.

Here at the Cabinet, one never knows what one might find, but a good rule of thumb is this: Just because something looks innocuous enough on the outside doesn’t mean it’s so on the inside. And sometimes the smelliest, foulest, most dangerous-looking things you could imagine contain the most wondrously lovely insides . . . if you know just where and how to open them.

Then again, sometimes the smelliest, foulest, most dangerous-looking things are exactly what they appear to be.

Really, the lesson here is that you can’t trust anyone and probably shouldn’t open any gifts, ever. Just in case.

. . . But that wouldn’t be any fun, would it? We certainly don’t think so.

Come help us unwrap this month, and let’s see what it holds in store.

Sunday Night Strange

I know, I know. I’ve been gone for a long while now, and you’re grumpy about it, and feeling maybe a bit self-righteous about it, and thinking to yourself, “It’s past time, isn’t it, you lazy, good-for-nothing Curator?”

Well. Allow me to toss a withering glare in your general direction and ask you to take your cheek elsewhere, thank you very much.

It’s not like I’ve been lounging about the Cabinet, re-reading favorite spellbooks and sorting through my collection of dancing shoes, reminiscing fondly about each pair’s doomed former owner.

(Don’t look at me like that. I wouldn’t harm someone just to get my hands on their dancing shoes. I may be a Curator and therefore in possession of both dubious judgment and an irregular personal hygiene routine, but my morals are intact, I assure you.)

(Now, if the owner of a fabulous pair of dancing shoes happened also to have broken into the Cabinet stores, and attempted to sneak away with Curator Bachmann’s collection of haunted musical instruments in order to enspell and then dispose of a prima ballerina and take her spot at the upcoming premiere . . . why, then, it is perfectly acceptable to, shall we say, cautiously incapacitate this person and take said fabulous dancing shoes for oneself. It’s all in the name of justice, you see.)

Now, where was I? You made me so indignant that I was forced to use parentheticals.

Ah, yes. The reason for my absence.

How to tell such a story? I’m not sure you will believe me when you hear it. And it’s rather embarrassing, in fact, so maybe I shan’t tell you at all.

What’s that? Are you actually begging to hear my story, like a spoiled child?

Well. If you insist. But don’t think I’ll give in to your pitiful whingeing again.

(Oh, who am I kidding? We Curators can’t resist telling our stories. You know this by now.)

So. Imagine this:

It is a Sunday, the most horrid day of the week because with it comes an unshakeable sense of impending disaster, otherwise known as Monday morning.

You decide to take a stroll and enjoy the noiselessness of your neighborhood at half past nine. Children are asleep. Adults are grumbling about their laundry, the twins’ lunches, the dog’s piddle on the rug.

But the streets are quiet.

And it is here, on these streets, at the corner of somewhere and thereabouts, that you hear a rustling.

You peek out from beneath your scarves and your layered felt hats, the necklaces you wear around your neck clacking against each other. The necklaces are made of carved sections of bone, each piece strung to the next with hair from a tribe of flesh-eating pixies. You wear them to protect yourself from evil and also from smelly people on the train.

A familiar face appears before you, and the delicious fear tickling your skin subsides. Why, it’s nothing exciting. It’s only your friend Percival

(What, don’t you have a friend named Percival? I thought everyone did.)

“Hello, there,” says Percival, bobbing his head about in the strangest of fashions. Perhaps he hears music you cannot? “I thought it was you.”

“Hello, Percival,” you say. “I was just out for my Sunday evening walk.”

“Oh, yes. Of course.” Percival blinks at you, his eyes watery and a bit gummy around the edges.

You say: “Percival, are you quite all right? You have a sick look about you.”

Percival says: “I’m afraid I’m quite ill.” His head is starting to fall this way and that like a child swinging about a bag of potatoes.

A thin line of laughter arises from the shadows. You turn, but nothing is there.

“Well, I must go,” says Percival, “for I have a sick look about me.”

Then Percival leaves you standing there curiously as he continues on his way. You blink, and his body buckles. Did he stumble on a crack in the walk? You blink again, and Percival is gone. You think you see small shapes scattering into the hedges like tumbleweeds, but you can’t be sure.

What an odd fellow, that Percival.

You continue on your walk, and for a time all is well. But then you turn a corner, and there he is again—Percival. Only this time, his skin is wriggling like many squirming things are itching to break out of their fleshy Percival-prison.

“Percival, my friend, you look rather smashing just now,” you say, for, as everyone knows, it is rude to comment on someone’s wriggling skin to his face.

“Percival, my friend, Percival, my friend,” whispers Percival, and then comes that laughter again. It is high and shrill. Really, it could be best described as shrieky, and it appears to be emanating from the rubbery crack forming diagonally across Percival’s face.

“Ah. Percival?” you point out helpfully. “Your face appears to be breaking in two. Or rather more like melting in two.” You peer closely. “I’m not sure what to call it, actually.”

“Your face! Your face! Your face!” Percival shrieks, and then runs away, his crooked limbs flailing everywhere like those of a marionette with cut strings.

He truly is an odd fellow. You ought to send him some fairy cakes to get his color up a bit.

Later, you reach your neighborhood’s little pond. It is flat and black and is actually the gateway to an imprisoned army of demons, but none of these people in their bright, cheery houses need to know that. Besides, you and your friends have long had these demons under control.

Truly. You have. No matter what anyone says.

And wouldn’t you know it? There is Percival, sitting by the water with his legs splayed like a child’s. Fish fresh from the water flap about him in the dirt. He has plucked off several of their fins; his mouth is slimy with guts.

“Face,” Percival whispers. “Face, face, face.” Then he holds up a mutilated fish for you to see.

“Percival, I’m not sure you should be eating fish fresh from the water like that,” you advise. “The water may not be . . . entirely safe. You know. Pollution and such.”

(Pollution there may be, but nothing humans can create is as foul as demon breath, and to the trained nose, this pond reeks of it.)

But you don’t tell Percival that. Even if you had wanted to, his ears appear to be sliding off of his skull.

In fact, his entire face is now peeling apart into five sections—eyes and nose and mouth and ear and ear. Gummy strings stretch between each separating piece of Percival-face. The pieces elongate and squash and flatten and squash again until they take the shapes of fat little men with swollen faces.

It is only then that you realize your error, and everything becomes clear.

These are the flesh-eating pixies from which you harvested hair to bind together your protective necklaces those many months ago—and you realize now, many months too late, that on that fateful day, you forgot to offer them your own hair in return for what you harvested.

You committed, in fact, an unthinkable pixie faux pas.

And of course they let you. They didn’t clear their throats or raise their eyebrows or give you any sort of body language cue that you were doing something wrong. No, the little flatulent devils just sat there and smiled, probably already plotting the details of this very night, right down to the last mangled fish fin.

“Oh, of all the rotten luck,” you mutter, as the pixies tumble out of their Percival-shaped tower and become themselves. What they lack in size they make for in numbers and a fierce adherence to the rules of trade etiquette. They drag you through the neighborhood by your scarves, through the forest, up the mountain, down the mountain, and up the next mountain, until coming to a stop in a wooded glen encircled by rocks—and it is here that you see an empty cage, waiting for you.

“What is the sentence for a botched exchange of hair?” you ask, as you are unceremoniously shoved into the cage. “Do remind me. I’ve forgotten.”

For answer, a pixie with a particularly gleeful expression floats up to meet your eyes. In his tiny hands are a pair of polished scissors.

He flies at your hair with a gleam in his eye, and you quickly calculate how long you will have to remain indoors after this. Three months?Four? Pixies love hair—especially that of humans—but they have a notoriously terrible eye for style, and whatever they have used to coat the scissors’ blades reeks of poison. No doubt it will take some time for everything to grow back.

When the first lock of your hair hits the floor, and the pixies let out a cheer, you sigh and clasp your hands. It could be worse, you suppose—and very well might be, if they get hungry while they work.

(But obviously they didn’t, for I am still here.)

(Well, mostly.)