The Cabinet has Received a STAR!

The Cabinet of Curiosities has received a STAR from Kirkus. Not a real one. Real stars are difficult to come by, even more difficult to preserve, and our specimen, in the mason jar under the third-story windowsill, has become dull and melancholy in his captivity. He will be replaced by this new one, we think, as it is really more of a figurative star and much more practical.

But in all earnestness: Kirkus, that venerable place known for chewing up books the way werewolves chew up children, has bestowed on our little collection of horrors a STARRED REVIEW. If you are confused as to what a starred review is, fear not. It simply means that the review has a star on it, like a Sneetch, and the star means that Kirkus liked the book a great deal, and to us, this is a vast and humbling honor. In fact, we’re all rather in a tizzy right now, fainting all over the furniture. You must excuse us. Would you like to see the review? Here it is:

~*~

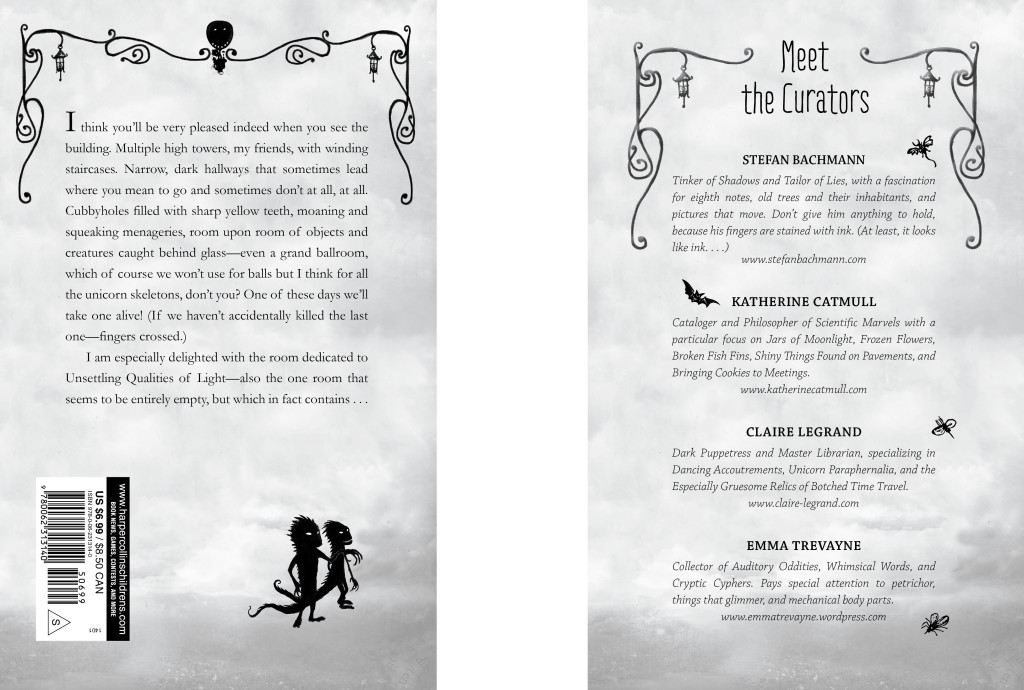

“Styling themselves ‘curators,’ four of horror fantasy’s newer stars share tales and correspondence related to an imaginary museum of creepy creatures and artifacts.

In addition to Bachmann, the authors include Katherine Catmull, Claire Legrand and Emma Trevayne. The letters, scattered throughout, record adventures in gathering the Cabinet’s eldritch collections or report allusively on them: “I just let them creep or wing about the place,” writes Curator Catmull, “and stretch their many, many, many legs. What jolly shouts I hear when the workers come across one!” The stories, most of which were previously published on the eponymous website, are taken from eight thematic drawers ranging from “Love” and “Tricks” to “Cake.” Along with a cast of evil magicians, oversized spiders and other reliable frights, the stories throw children into sinister situations in graveyards, deceptively quiet gardens or forests, their own bedrooms and similar likely settings. Said children are seldom exposed to gory or explicit violence and, except for horrid ones who deserve what they get, generally emerge from their experiences better and wiser—or at least alive. Jansson’s small black-and-white vignettes add scattered but appropriately enigmatic visual notes.

A hefty sheaf of chillers—all short enough to share aloud and expertly cast to entice unwary middle graders a step or two into the shadows.” (Horror/short stories. 10-13)

Isn’t it lovely? Evil magicians, oversized spiders and other reliable frights? Lovely. If you like odd and scary stories, too, or if you have a pet, child, or corpse who likes odd and scary stories, you can pre-order this collection at one of these fine retailers: amazon | barnes & noble | indiebound | the book depository | itunes | books-a-million

As for us, we’ve revived from our fainting and are off to collect more stories for the coming weeks. Thank you, Kirkus, from the bottom of our damp and echo-y hearts.

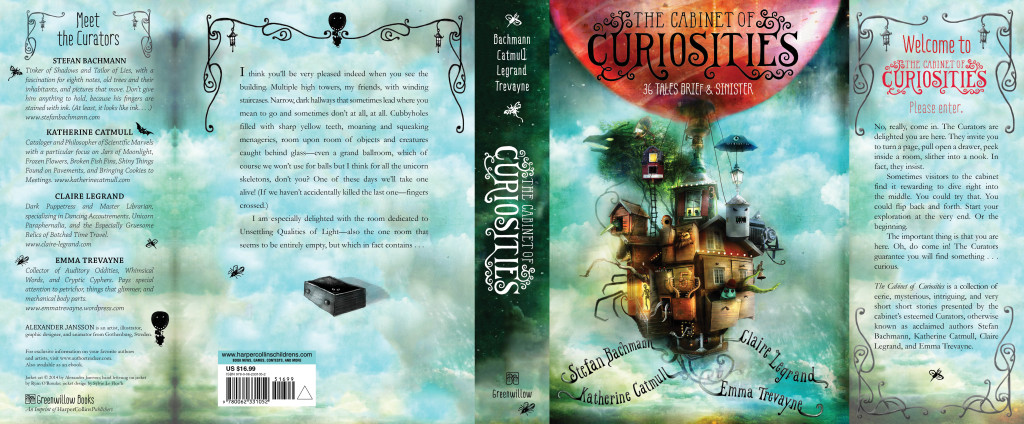

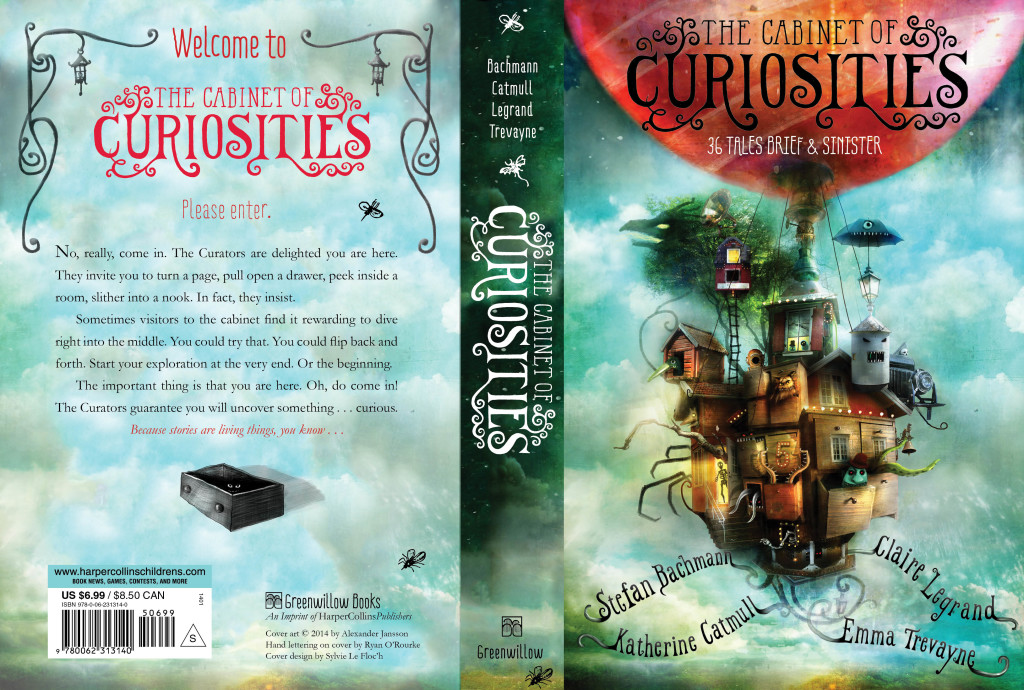

The CABINET OF CURIOSITIES Jackets

Hello, dearest readers,

Did you know that, in less than two months, The Cabinet of Curiosities releases in bookstores everywhere?

That’s right: On May 27, you can have a copy of our 36 tales brief and sinister for your very own–in e-book format, paperback, and/or hardcover.

You can even pre-order it at these fine retailers, if you so desire: amazon | barnes & noble | indiebound | the book depository | itunes | books-a-million

(And if you’d like to read about how important pre-orders are to the authors you love, please do refer to this piece written by our own Curator Legrand.)

Today, we want to share with you a couple of beautiful treats to whet your appetite for this momentous day–the glorious jacket for the hardcover Cabinet of Curiosities, and the equally divine paperback cover (click on thumbnails for larger images).

Enjoy, and be on the lookout for more bookish treats in the weeks to come.

Excitedly,

Your Curators

~*~

HARDCOVER

PAPERBACK

AND, A SNEAK PEEK AT THE INSIDE FLAPS (IN WHICH YOU GET A TASTE OF ALEXANDER JANSSON’S BEAUTIFULLY MACABRE ILLUSTRATIONS)

The Warmth of Secrets

High in the trees, the birds build their nests, a constant and ever-changing labor, their homes never the same shape from one hour to the next. Twigs weave with leaves weave with bits of fluff to create warm homes for their delicate eggs.

But this is not the only thing they use. They are only the things you can see.

The birds awoke Annabelle from a rather pleasant dream that she couldn’t remember the moment she opened her eyes. She was quite certain it had been a nice dream, though, from the feeling, like she’d had a big warm mug of hot chocolate with whipped cream and marshmallows. Annabelle stretched and climbed from her bed. Her school clothes were already laid out, selected by her mother the night before, but she stayed in her nightgown as she padded to the window and spread the pink curtains she secretly hated.

A small, night-black bird lit on the sill just the other side of the glass, a fine wisp of something glimmering slightly in its beak. It stayed for only an instant before flying off again, becoming a speck and then nothing at all in the distance. The trees in the garden of the Nelson house were just beginning to be touched by spring and sunlight, the tiny green buds tinged with gold.

Downstairs, the kettle whistled. Annabelle dressed and arrived in the kitchen just as her father took his first sip of tea. Her older brother, who was thirteen and very grumpy, left without a word from a mouth filled with toast, the front door slamming behind him.

“Good morning,” said her mother. “Oatmeal?”

Annabelle secretly hated oatmeal even more than she secretly hated her pink curtains. She couldn’t remember when she’d ever liked it, though she must have, surely, when she was too young to know better, or her mother wouldn’t think she still did. But there wasn’t anything else she wanted instead, so she said yes, and put half the sugar bowl on it when her parents were making a fuss over whatever had landed on the bird feeder outside.

It was very rare, apparently. Her father peered through a pair of binoculars that, this close, must have allowed him to see the glint in the bird’s eye.

This time of year, it was difficult to get them to talk about anything else. It was all feathers and eggs and whether this crow was the same one they’d seen last year. Sometimes, only inside her head where no one could hear, Annabelle wondered if she’d be more interesting if she had a beak. Still, she supposed, it kept them from pestering her too much about whether she’d done all her schoolwork or cleaned properly behind her ears or tidied up the mess in her room.

The rest of the day, until the afternoon, passed just as the morning had—which is to say, quite normally. Annabelle went to school and talked to her friends and only raised her hand in those subjects she enjoyed, staying silent and invisible during the ones she didn’t. The final bell rang through the classrooms, and she gathered up her things for the walk home.

Three corners away from Annabelle’s house, it happened. She saw everything, saw what was about to happen and the seconds that would follow, but there was nothing to be done. Nothing at all except to stand, mouth open in a scream that made no sound, as the bird hit the windshield of a car stopped at the lights and bounced off again, arcing through the air in abnormal flight, to land at her feet.

“Oh no,” Annabelle said, when her voice returned, lost amongst the hooting of car horns. The poor creature twitched at her feet. Mother, mother would know what to do, how to save it.

It felt soft in her hands. Soft and broken. “Hold on,” she whispered. “I’ll keep you alive.”

But she couldn’t. Two corners from her house, it gave a final, tiny chirp, almost a sigh, and went very still. Annabelle felt the stillness as firmly as if it had been a slap, and then a curious coldness through her whole body which turned, quickly, back to warmth from the sun overhead.

“Oh, no,” said Annabelle again. “I’m sorry, little bird.”

She did not, as usual, walk in the front door and announce she was home. Instead, Annabelle veered around to the side of the house, where the earth below the rosebushes was thick and damp from the spring rains. Digging with her fingers wasn’t easy, and soon they were black with dirt, but she kept on until the hole was deep enough.

There wasn’t so much as a whisper from the trees above. Patting the soil back into place, Annabelle looked up at the line of birds on a branch.

Watching her.

“There you are!” said her mother when she heard Annabelle come in. “Where have you been…and what have you been doing? Go wash up.”

Annabelle didn’t answer. The bird, beyond her mother’s help, now felt like a secret thing.

She scrubbed her hands. Ate dinner. Went to bed. Dreamed of flying.

And the voices woke her. So very many voices, like being in a room full of a thousand people all talking without a single pause. Was she still dreaming? Annabelle didn’t think so, though it was still night, no hint of light peeking around the hated pink curtains. She threw them apart and stared from the window.

“Buried him, she did.”

“Curious.”

“There’s a nice lot of crumbs down by the river bend. Get them before those greedy swans do.”

“There’ll be a nice breeze today. Anyone fancy a trip south?”

“Can’t. Expecting a hatch.”

Annabelle blinked.

The birds were talking. If she listened, carefully enough that her head began to ache, she could hear their normal chatters and chirps with her normal ears, but their voices, their words were loud inside her head.

She nearly screamed. She nearly ran to her parents’ room to shake them awake and tell them, but she didn’t. This, too, felt a secret thing. They’d think she was mad, or making up stories. Or—perhaps worse—they’d believe her and ask a thousand questions of a thing she wasn’t entirely certain she believed herself.

“Anyone have any spare twigs?”

Very purposefully, Annabelle climbed back into bed, pulled the blanket over her face, and lay in the dark, hearing all the voices until the sun came out. She dressed in Saturday clothes and went downstairs to breakfast.

When her mother asked if she wanted oatmeal, Annabelle said yes.

It came out as a squeak. Annabelle coughed. “Yes,” she repeated carefully. Her mother didn’t notice.

Her parents exclaimed out the window about the beautiful feathers on this one. Annabelle listened to it complain that those blasted starlings had stolen all the good seeds. Her brother stomped into the kitchen. “I’m going to spend the day at Tom’s,” he said. Annabelle’s mother nodded absently.

But Annabelle stared at him. It was a lie, and she didn’t know how she knew this. It left his mouth and drifted over toward her, a thin, glimmering thread of a thing she caught in her hand.

“And I’m going outside,” she said. Nobody heard her, which was perhaps a good thing. Her voice, once again, had not sounded entirely…human.

The birds were louder out here, much louder. The lie still clutched in her palm, Annabelle covered her ears, which didn’t help a bit. Down at the bottom of the garden, there was a tree just perfect for climbing. Every summer since she could remember, her father had promised to build a tree house in the low, wide branches, but he never had, and how she and her brother were probably too old for such things. It was easy enough to place her feet and hands just right, though, and rise up in the tree as simple as if it was a ladder.

She stopped when she found what she was looking for. The first, perfectly round nest, built of twigs and leaves and bits of fluff, and thin, silvery wisps. She touched one and knew Mrs. Livingstone four doors down on the road had thought of putting poison in her husband’s tea, but had never done it. She touched another and learned the man who came to clean the windows had always wished to be an opera singer.

She touched a third and knew—although she didn’t need to be told—that she hated her pink curtains.

A raven landed on the branch beside her. Annabelle startled and slipped, but didn’t fall. It fixed a knowing, wise gaze on her.

“We know all your secrets, all your lies,” it said, and once again, if she really tried, she could hear the ordinary birdsong, and the words in her head, all at the same time. “They line our nests, they keep us warm in the frosts. And now, you know ours.”

“Why?” Annabelle asked.

“We hear everything,” said the raven. “We are everywhere. Humans pay us no notice as they walk beneath our trees, thinking and saying the things they never should.”

Annabelle looked at her brother’s lie, still stuck to her hand. “I don’t understand how they keep you warm.” It made her feel cold, even on the pleasant spring morning.

The raven cackled. “You will,” it said. “Oh, you will. And soon.”

Annabelle climbed down. All day the voices crowded inside her until they fell silent with the evening. Her bones felt odd inside her. She went to bed early, the pink curtains billowing in the breeze from the window she left open as she fell asleep.

In her dreams, feathers crawled over her skin. Her feet shortened and toenails grew. The voices started again in the night, and Annabelle hopped from her bed, up onto the windowsill.

She chirped, once, and flew into the dawn, listening for dreams, for secrets, for lies with which to build her nest.

April Takes Flight…

An unkindness of ravens, a deceit of lapwings, a lamentation of swans…

A storytelling of crows.

This month, we explore a room in the Cabinet filled with rustling feathers and secrets chattered and chirped from the shadows. We’ll turn over objects and, perhaps, crack their shells to see what hides within. Or we’ll watch as they unfold their wings and perch, just for an instant, on the windowsill, talons chipping the paint, before they soar off for lands unknown.

There may be birds that carry messages of sorrow and mischief, ones who refuse to leave their nests lest anyone discover what’s woven in with the twigs and leaves, and ones who’ve seen, with their sparkling-jewel eyes, far more than we ever will.

Fly away with us, dear and curious readers, as we learn more of these cunning and watchful creatures.

The Curators

Butterfly Blood

In the middle of a wide, snowy field, beneath a solitary tree, two nuns stood, side by side. Their black habits—blacker than the tree—flapped about their ankles. Their white wimples—whiter than the ground—framed their faces. Their sensible shoes, patent leather and pointy-toed, shone dully in the winter light.

The nuns did not move a muscle.

A man was approaching them from far across the barren field, tramping steadily through the frost and the silence. The man’s head was far too small. Or perhaps his body was simply too large. At any rate, he had a freakish look about him, like an ogre, and his skin had a pale, greenish tinge, a slimy-wet sheen.

The nuns regarded him as he approached, their expressions inscrutable. One of them, the smaller one, had her eyes opened very wide, but whether it was out of surprise or simply the permanent state of her face was impossible to say.

As the man approached, it became apparent that he had no fingers on either hand, only stumps, stopping at the first knuckles. When he ducked his tiny head, one could see he had no ears either, only holes on either side of his face.

The smaller nun didn’t say a word, but her eyes grew a fraction wider.

The man stopped several paces away, just outside the spreading reach of the tree. He bowed heavily and then straightened, shifting from foot to foot.

The nuns turned slowly and looked at each other. Then they looked back at the man, and the taller of the two held out a hand, as if to say, Have you got it? We have walked many miles. We have waited in the cold. Give it to us.

The man with the too-small head looked at the tall nun. Then he grinned gapingly, and the nuns gasped in unison because he had no tongue. No ears. No fingers. No tongue. Eyes, he had, but those are not nearly as useful as most assume.

He was the perfect messenger, of course. He could never tell on anyone, or whisper a tale, or scribble a note. That was why the nuns had called him. They should not have been surprised.

The taller one regained her composure and held out her hand again, more insistently this time.

The man nodded his tiny head, and his eyes lit up, and he slipped something from his sleeve.

It was not a bottle, or a packet, or anything like that. It was a butterfly, sapphire-winged and veined with black, and it emerged out of his sleeve and came to rest delicately on the end of one of his poor old stumps, flapping slowly, feelers curled against the wind.

The nuns looked at each other again. The smaller nun’s eyes were very nearly rolling down her cheeks. The man with the too-small head simply smiled at the butterfly in his palm, a look of wonder on his face.

Finally the tall nun nodded and inclined her head formally toward him. Then she put the butterfly in a small cage made of wire, and the two nuns went away across the field.

***

The man with the too-small-head watched them go, and watched the glimmer of the blue butterfly-wings in the cage.

When they were gone, he shook his head and grinned again, and he didn’t exactly disappear so much as simply move someplace else, someplace that was not the snowy field, but was perhaps just behind it, very close by.

***

The nuns arrived back to their nunnery very late. Before going inside, they made sure to pat some wet earth on the knees of their habits and clump a bit around the frosty heels of their sensible shoes, before finally letting themselves in through the great door.

They had herbs under their arms, but they had collected them the day before so as to have some time free to seek out the man with the too-small head.

They looked around stealthily as they entered the nunnery, stood still and nodded as other nuns passed by. The cage with the butterfly they kept hidden, clutched tightly behind their backs. When the Mother Superior saw them, she twinkled at them, her eyes very bright, and they both inclined their heads as she passed, but their faces remained like stone.

As the Mother Superior went on down the corridor, their eyes followed her, and the younger nun’s mouth may have twitched a bit—just a tiny, tiny bit—but in that flat, empty face it was like a bomb blowing up.

***

The nuns took the wire cage to their cell and sat a while, admiring the butterfly through the mesh. The nunnery was an austere place, busy and soft, full of shadows and whispers and echoing songs. The music was often rather sad and the colors were either dark or white, and so it was something of a marvel, this blue-winged butterfly in the gray cell.

The smaller nun, finally, looked at the taller one in a questioning way, as if to say, Do you think it will do the trick?

And the taller one looked back, eyebrows raised, as if to say, Who can know? They promised it would. Those wild things in the fields and moors, they promised, and I know they lie, but it should. It should do the trick.

Then she undid the latch of the cage with two long fingers. The butterfly crept out, blue wings flickering tentatively.

It was about to fly away, about to beat those wings once, twice, and flutter toward the ceiling. . . .

But the younger nun took a wooden mallet from the folds of her dress and smashed the butterfly onto the table top.

***

The nuns let the butterfly sit, squashed to the table, overnight, exactly as they had been instructed. Then they scraped the blue from its wings and the clear, watery blood from its veins, into a tiny thimble-sized bowl and set it out on the windowsill, in the cold, fresh air.

The smaller nun looked at the taller one, and her eyes said, I hope it works. We haven’t much time left. And what if someone starts to suspect?

And the taller one nodded in a way that meant, It will work.

The moon came out, half-full, like a sleepy eye, and squinted down at the bowl on the windowsill, and at the nuns, who looked away quickly and closed the casement.

In the bowl, the blue and the blood sat and drank in the moonlight, but also the night and the shadows and the cold, and the nuns went down to the evening mass and tried to forget about it until it was ready.

The Mother Superior was at mass, of course, and though her back was toward the two nuns, anyone raising her head from the hymn-book might have noticed the smaller nun staring at the Mother Superior, her eyes so wide and still. . . .

***

Five weeks earlier, the nuns had gone to the Mother Superior and asked her a question.

“Please,” the taller one had asked, and her voice was surprisingly soft and regular-sounding, papery and cool. “Might we have the third Saturday of next month off?”

The Mother Superior had twinkled at them. She said, “Of course you may have a day off! But not that Saturday. We’ll need you here for the weeding and the churning, and it’s baking day. You may have the fourth Saturday off. I will mark it down.”

You never would have guessed the nuns’ disappointment. They had looked at each other briefly, had nodded at the Mother Superior, and had slipped away without another word. But behind their placid faces, anger was roiling and tumbling like flames.

***

Here was the situation: a great violinist, Master Garibaldi, was on a tour across the continent. He was playing Bach, all the Chaconnes and Voluntairs, and the nuns pined to hear it, and pined to see him, too.

They could not tell the Mother Superior this. They were sure she wouldn’t understand how lovely Maestro Garibaldi was, and how his hair shook like a lion’s mane when he played his violin and how his music felt like a lamp, glowing behind your ribs. And so, when the tall nun and the short nun had been told they could not go to the City the day of the concert, they began to plot.

They read great grimoires in the library and went on long walks across the moors, and came upon the creatures of stone and moss in the wild hills, and all the while Maestro Garibaldi crept closer and closer across the continent toward the City, and the nuns worked more and more urgently, until at last they had it all, everything they needed for their plan, everything but the last bit, the most important bit.

There is a price to pay for all good things, one of the old, crusty books in the library told them. The highest price is not what one pays one’s self, but what one makes others pay for one’s own happiness. If you are willing to, you can have anything you like in life, only know that something beautiful must die.

The nuns had no compunctions about this and had gone to the man with the too-small head, and fetched the butterfly, and squashed it to the tabletop.

***

When the nuns were sure their mixture had ripened well on the windowsill and had turned into a good thick paste, silver-gray and speckled with flecks of shimmering blue, they brought it out into the early morning, to an open place where the wind blew strongly.

There, they set the bowl on the ground and the wind dipped into it at once, picked up its contents and blew it into the air. The flakes whirled a moment and then began to form a shape. A human-shape. A nun in a black habit—blacker than the stone walls of the nunnery. A white wimple—whiter than the nun’s teeth as they smiled and watched.

The wind swept over again, and the last of the mixture grew into the second nun, small and stout, with eyes like marbles.

The two sets of nuns stood looking at each other, one pair smiling, the other not. Then they nodded to each other and one pair set off into the nunnery and the other took off its sensible shoes and put on ones with bows and went to the City, where it heard the great Garibaldi playing on his violin and fairly well swooned.

***

That night, the wind came and reclaimed its breath from the delicate shell of butterfly blood and moonlight, and the false nuns fell to nothing. But by that time their namesakes where comfortably in their beds and fast asleep.

They weeded twice as many beds in the herb garden the next morning, those two nuns, and churned three times the butter, and perhaps, if one had watched them very closely, one might have seen them wink to each other over their work, their heads all full of music.

The butterflies of the area were less pleased, however, and there was an infestation the next year in the nunnery’s dining hall, small onyx-winged insects all up the rafters and under the edges of the plates. No one could understand why it happened, not even the two who had caused it.