Author Archive

Abram Brown’s Birds (Dead and Gone)

*

Curator’s Note: An eerie little tune called “Old Abram Brown” inspired the telling of this particular tale. I suggest you listen to it whilst you read, and pay particular attention to the lyrics below.

*

Old Abram Brown is dead and gone You’ll never see him more He used to wear a long brown coat That buttoned up before “Old Abram Brown” from Songs for a Friday Afternoon by Benjamin Britten*

In a mud-colored city piled high with towers, there lived a man named Abram Brown.

The city was a drab sort of place, though it hadn’t always been. Factories sat in squat buildings on the perimeter, and the smoke they produced leeched the color out of houses and horses and cabs and gowns until even the grass in the park turned crunchy and gray.

Abram Brown fit in quite well here. He wore a long brown coat that nearly brushed the ground, and his hair was gray, and his face was rather gray as well.

In fact, he looked much the same as his fellow citizens and might have gone entirely unnoticed in the drone of the city, just like most things were—had it not been for the flock of birds that followed him wherever he went.

The birds formed a sort of buffer around Abram Brown, his own personal shield, for you didn’t want to get too close to Abram Brown’s birds. No, you did not. They flapped silently about him, their feathers slick with the oil from the sky. They alighted on his shoulders and nested in his hat and burrowed into his clothes to poke their heads out between the dirty brass buttons of his coat.

Their eyes were black and beady, like any bird’s, but it wasn’t the eyes you had to worry about.

What you had to worry about was how, if the birds happened to glance your way while you carried on with your business, they would whisper while they watched you.

Their beaks did not move, but you knew it was them, all the same.

There was no mistaking the whispers of Abram Brown’s birds.

*

Octavius Sinclair hated his name but he had found his peace with it, even though the boys at school called him Octo-Face and Octavi-pus and all other kinds of horrid things.

Octavius was the sort of boy who made peace with things quite easily, because his mind was bright and open like the inside of a polished bell. This isn’t to say he was empty-headed. It’s simply to say that thoughts slid in and out of his mind with ease, never staying there too long to cause trouble.

For example, while most people either found themselves disgusted or tiredly complacent about the state of the crunchy, smoke-covered grass in the park, Octavius had decided it was actually rather beautiful.

“Is it true,” he had asked his father once, when they passed the park, “that the grass is bright green in some places?”

“I suppose,” his father had said briskly, checking his watch. He was always checking his watch, and polishing its smog-smeared face.

“Aren’t we special, then, to have our grass be such a lovely gray color?”

“What are you on about?”

“I mean, it’s lovely and gray like a dream. Like when you come out of a dream and everything is soft, and you hang there between two worlds. Like that, Papa.”

His father had snapped him hard into the street. “Keep up. You’re dawdling.”

Every day when Octavius walked home from school in his stockings and buckled shoes and that horrible burgundy jacket with the dirty brass buttons, he walked by the park where Abram Brown liked to take his birds in the afternoon.

Octavius had been quite small when he happened upon Abram Brown for the first time, right in this very park.

It had been the first day anyone had called him Octavi-pus, to the delighted jeers of all the boys in the school courtyard, so he had taken his time walking home. He had needed some time to himself to figure out how he felt about the day’s events.

Instead of paying attention to what lay before him, Octavius had been staring at his feet while walking. He therefore did not see the cloud of birds coming at him, and walked straight into it.

Most of the time, when someone walked too close to Abram Brown’s birds, they squawked and shrieked and flapped around until the intruder retreated.

But that day, they simply fluttered quietly to Abram Brown until he was covered in them, and stared at Octavius. They did not even whisper.

And Octavius, his mind so shiny clean, smiled at them, and said, “What a lovely collection of birds you have, sir.” Then he pulled out the sandwich from his pocket, which he had not had the appetite to finish after the incident in the courtyard.

He sat on a bench with Abram Brown and shared his bread with Abram Brown’s birds.

Once all the birds had eaten, Abram Brown had peered out from his beard and said, “My name is Abram Brown.”

“I know who you are. Everyone knows who you are. They say you are mad, and that I shouldn’t talk to you.”

Abram Brown had said, “And yet you are talking to me right now.”

“Everyone says you should not be mean to others, too, and yet everyone acts cruel anyhow. So why should I take them seriously?”

A bird on Abram Brown’s shoulder had cocked its head.

“Yes,” Abram Brown had said. “That makes quite a lot of sense to me.”

*

Every day after that, Octavius Sinclair took the long way home from school and met Abram Brown in the park at that same bench, and shared whatever was left of his lunch with Abram Brown’s birds.

It was a peaceful ritual, for a while, in the dream-colored park with the gray sunlight struggling down.

Until it wasn’t peaceful anymore.

Until the boys from school followed Octo-Face home one day, and spied upon him, and decided to have some fun.

*

The ringleader was a thirteen-year-old boy who wasn’t as horrid inside as he pretended to be, but we cannot excuse him for that.

His name was Horace Wickham, and Octavius baffled him.

Horace hated this city. He hated its sky full of towers and smoke. He hated that, no matter how many times he washed his hands, they still looked dirty.

Most of all, he hated the park. Parks were supposed to be green and bright, clean and full of flowers.

Didn’t anyone know that?

Didn’t anyone care that they lived in such a dirty heap of a place?

Horace cared very much. He wished he could leave, but he was only thirteen, and a small part of him worried that in fact the tales of bright green grasses and clear blue skies were merely legends from a long-ago time or a far-off world.

The hatefulness of his circumstances built up inside his heart and turned him rotten.

How could that stupid, soppy, thin-shouldered Octavius Sinclair walk about smiling all the time? How could he look around him and still be happy? It was inexplicable. It was unfair.

So Horace led the other boys from school to the park. He spied upon Octavius, and his insides churned hot and black.

“Here we go,” he whispered to the boys huddled around him. He fished out some stones from beneath the bristly black hedges and curled his fists about them.

For a moment, a thought came to him that this was a terrible idea. He wasn’t a bad boy, so he should not be acting like one.

But the stones in his fists were cold and sharp and covered in filth. The slick and slimy feel of them—and of the air, and of his own soiled skin—made Horace’s heart boil over with hate.

It was not fair, for someone to find such joy when he could not.

“Now!” he shouted, and the crowd of boys leapt out from beneath the hedges and began to throw.

*

The stones fell from the sky in showers of pain, striking Octavius’s head, arms, and stomach. No matter where he turned, they struck him. He was caught in a storm of stones and frantic black feathers.

Where was Abram Brown?

Octavius cried out in terror and fell to the ground, covering his head.

That is when he saw the bird—one of the younger ones, with a bright yellow beak and matching feet—lying on the ground in front of him. Its head had been split open, and it laid there, broken on the pavement, crooked and glistening wet.

Octavius began to sob and gently tucked the bird underneath him as he huddled there, shaking. His fingers came away stained red, and it was the brightest color he had ever seen.

He was so caught up in his grief and terror that he did not at first notice when the triumphant laughter of the boys from school turned to screams.

He did not notice when the cloud of birds left him, gathered together in one great shining black clump, and dove—pecking, biting, tearing with their tiny yellow claws.

When silence fell, it did not register with Octavius until a few long moments had passed.

He uncovered his head and dared to look up.

The first thing he saw was that the birds were gone. He saw not even a feather, heard not a squawk.

The second thing he saw was that the boys from school were gone, too—although not in the same way. The sight of them there on the ground, all red and misshapen, slid right through Octavius’s mind and out the other side.

It was not a sight worth holding onto.

The third thing Octavius saw was old Abram Brown’s long brown coat, lying on the soot-covered pavement, empty as a rotting fruit peel.

*

That night, Octavius Sinclair heard whispers in his dreams. Even when he woke up to fetch a glass of water, he still heard them—the same whispers, following him into the waking world.

At first, Octavius could not understand what these whispers said. He drank his water and tucked himself back into his rickety white bed and sat very still to listen.

Eventually, he pulled out three words from the whispers: Dead and gone.

They came to him, over and over. No matter how hard he tried to push them through his mind and out, they would not budge. They stuck there, right behind his eyes, and built and built. The words overlapped and fell apart and came back together again, but Octavius could still understand them.

Dead and gone.

Dead and gone.

When a sharp knock came at Octavius’s window, he got right up and opened it.

He knew, by then, after hours of listening to these whispers in his head, what he would find. He had begun to recognize the sounds.

A black bird hopped onto the window sill. It tilted its shiny round head and stared at Octavius.

Dead and gone.

“I know,” said Octavius. “Poor old Abram Brown.”

The bird snapped its beak open and shut, flitted up onto Octavius’s shoulder, and stayed there.

Together, they sat by the open window and looked out into the smoky night sky, waiting.

A sound came to them from somewhere out in the darkness—the sound of a thousand flapping black wings.

*

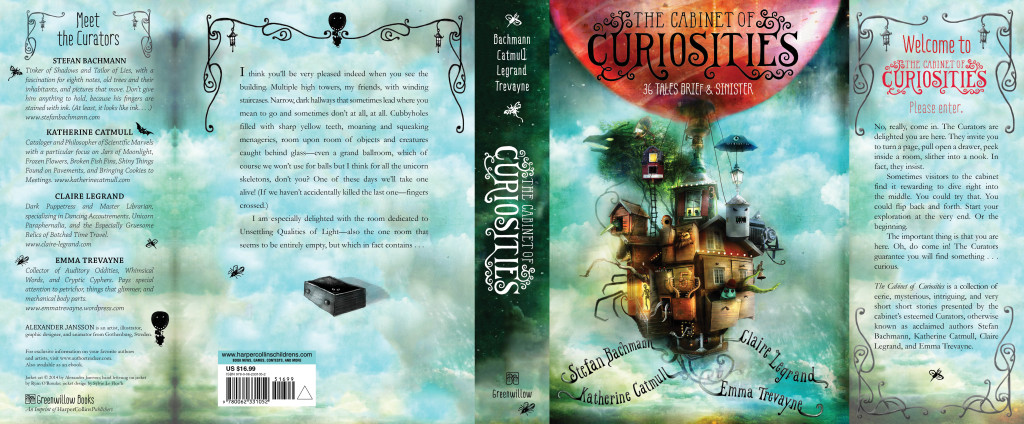

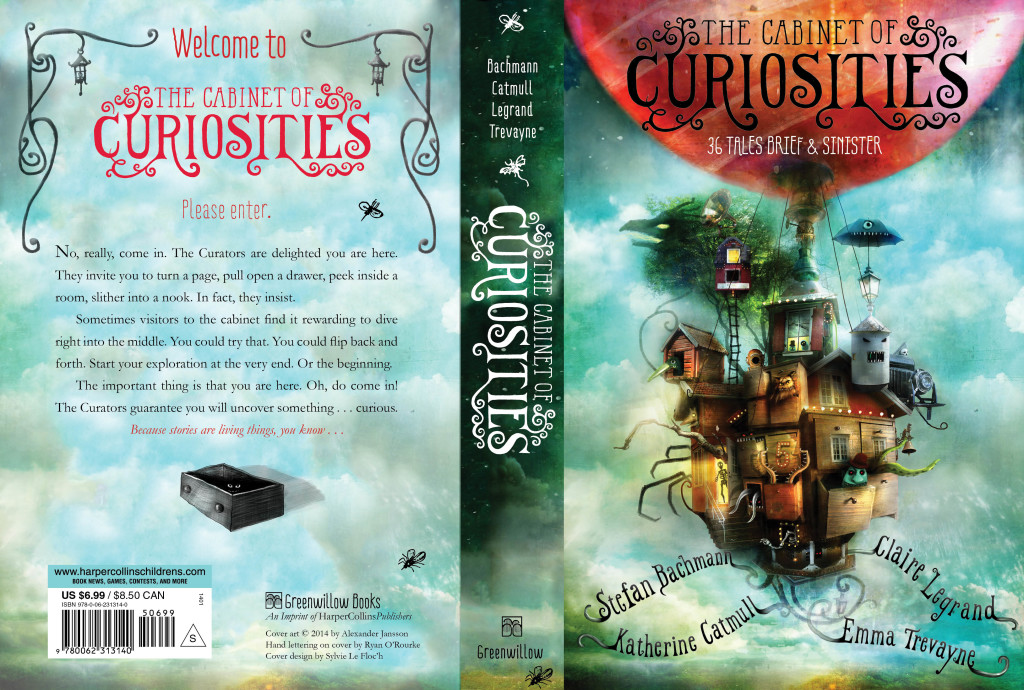

The CABINET OF CURIOSITIES Jackets

Hello, dearest readers,

Did you know that, in less than two months, The Cabinet of Curiosities releases in bookstores everywhere?

That’s right: On May 27, you can have a copy of our 36 tales brief and sinister for your very own–in e-book format, paperback, and/or hardcover.

You can even pre-order it at these fine retailers, if you so desire: amazon | barnes & noble | indiebound | the book depository | itunes | books-a-million

(And if you’d like to read about how important pre-orders are to the authors you love, please do refer to this piece written by our own Curator Legrand.)

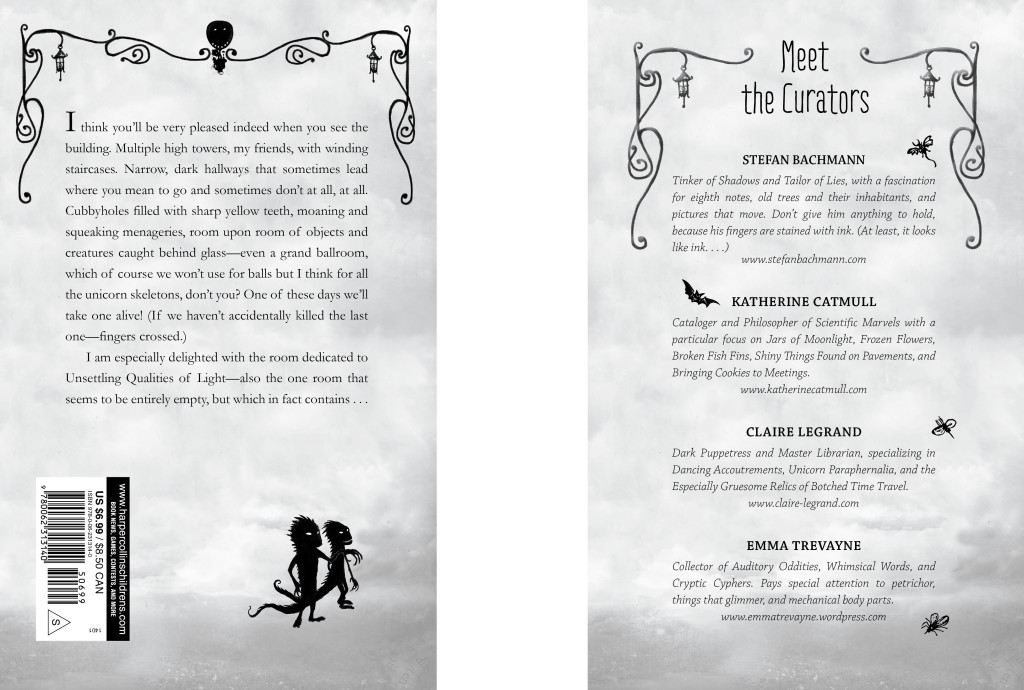

Today, we want to share with you a couple of beautiful treats to whet your appetite for this momentous day–the glorious jacket for the hardcover Cabinet of Curiosities, and the equally divine paperback cover (click on thumbnails for larger images).

Enjoy, and be on the lookout for more bookish treats in the weeks to come.

Excitedly,

Your Curators

~*~

HARDCOVER

PAPERBACK

AND, A SNEAK PEEK AT THE INSIDE FLAPS (IN WHICH YOU GET A TASTE OF ALEXANDER JANSSON’S BEAUTIFULLY MACABRE ILLUSTRATIONS)

Your Secrets for a Storm

Miranda had been taught by her mother, and her mother had been taught by her mother, and so on, back for a hundred generations in the kingdom of Aurestra, that little girls must never tell the wind their secrets.

Boys were all right; boys could shout at the wind until their throats bled, and the wind of Aurestra would pay them no notice. Boys pretend to be wild, but they’re not very much, not truly, not where it counts, and the wind only deigns to pay attention to creatures like itself.

Wild creatures.

Girls. Not women, but girls. Girls, because they have fire in their blood and storms in their eyes—the old fire, the ancient storms, of the time before cities. Before schools and science and libraries. Before the king’s palace was built. But girls must not show it, they must not unleash themselves, no—because girls are meant to be soft. They are meant to be sweet, and pretty like rose petals, and quiet, above all else. Quiet, quiet as sleeping birds tucked up inside their feathers.

Women are all right, too. They live behind veils and inside windowless carriages. They are forces of nature—though you wouldn’t know it—for they carry the old fire as well. But they have learned how to tame their power, and how to set it loose. Mostly the former, though. Mostly, they keep it quiet and coiled tight inside them, and only let this power out when it is safe—when they are alone, or when they are with their sisters behind heavy closed doors.

Because that is the way it is supposed to be. So say the laws of Aurestra. So say the frowning men. So say the looks on boys’ faces, wide-eyed and fearful, because they have been taught by their fathers about the dangers of girls—if the girl has not been raised right, that is. A girl like that might give in to her power.

So the wind ignores women. The wind doesn’t have the patience for them, with their veils and their whispers, and how they have hidden themselves away.

Girls, though—girls are only just beginning to understand the power they carry inside them, and so they must be watched over, and taught carefully by their mothers. And though a girl might be bursting with secrets, she must never shout them, shriek them, howl them to the wind, even if that’s exactly what her blood and bones are telling her to do.

Because the wind cares nothing for the laws of Aurestra. Single-minded, the wind longs for the way things used to be, when the world was ruled by queens. When girls ran wild, without veils, with bare feet, with hair long and tangled, with hearts open and loving, wanting to be kissed.

For some time now, the wind has been waiting for a girl to come along—the right kind of girl for the wind; the wrong kind of girl for the grim, white-haired kings of Aurestra.

A girl with secrets on the tip of her tongue.

A girl with power at the tips of her fingers.

A girl like Miranda.

*

Miranda walks through Aurestra’s central market. She is only twelve years old, but she feels heavy and burdened like an old woman. For most girls, it isn’t so hard to stay quiet. Or it is hard, but manageable, at least.

Not so for Miranda.

Staying quiet, staying soft, staying still, still, still has been eating away at her since she reached the Age of Refinement and was given her first veil.

Miranda wants to run, but she doesn’t.

No. She wants to race, to tear along the cobbled pavement until her feet hurt. She wants to yell, and sing—not the lilting, warbling tunes her stiff-robed tutor forces her to learn. No, something else, something different. Something that would shock her fellow shoppers and bring the censors out from the courts to seize her. A howling, savage, discordant song.

Like the wind.

Like the wind gliding softly through the winding aisles of the marketplace—tickling her fingers when she reaches for an apple, a plum; her fingers are the only parts of her not covered in fabric.

Like the wind, but a hundred times stronger than it is right now.

A thunderstorm wind. A hurricane wind. A song like that.

Miranda saw a hurricane once. It was dreadful. She was safe in her father’s sturdy stone cottage, and from the attic window, she could see the southern bay. The water surged in waves, destroying the docks. The wind knocked the boats together like they were less than toys, tearing them apart into splinters and planks.

It was dreadful, yes—and beautiful, too. Miranda had watched, her nose pressed to the crack in the boarded-up window, and she had not been able to help it:

She had let out a horrible, soft, desperate cry.

These winds, these winds, this power—this was what lay cooped up inside her. This was what she was not allowed, never allowed, to touch. If she did, if she broke the law and let it loose, what would become of her? Of her mother?

The Aurestran kings were not known for their mercy.

So Miranda cried, alone in the attic—but not the soft, delicate tears of a wounded damsel. Deep, wild sobs that wrenched her throat into knots, and the sounds of the hurricane drowned it out so that no one downstairs could hear her.

But the wind heard her. It heard her and thought, Ah. Could this be the girl? The wind thought it just might be, but it did nothing. The wind must wait for her to come to it. That was the way of things; a wind cannot just approach a girl and whisper terrible things across her skin, and coax her to tear down her kingdom.

The girl must find the wind herself. First, before anything else, the girl must tell the wind her secrets. That will be the invitation.

From then on, the wind watched Miranda.

It knocked against her window at night, and when she went to look out, she found no one there. And when she returned to bed, her skin was hot and itchy, and her dreams were restless.

When Miranda took her horse out to the fields to check on her father’s sheep, the wind chased at her heels, whipping her veil around her.

And when Miranda is twelve years old and in the market, when she brings her fingers out from beneath her cloak to grab a plum, the wind teases her skin.

And Miranda can bear it no longer.

She hurries as quickly as she dares to the outskirts, and then down the path leading north to the woods, and once she is out of sight, she runs. She runs, she tears, she flies. She drops her wrapped parcels from the market, and she tears her skirts on brambles. By the time she stops to catch her breath, she has reached one of the high meadows, in the foothills. She rips her veil from her head, and she falls to her knees, and screams.

Maybe there are farmers nearby, or shepherds, who happen to be close enough to hear her. They will report her to the censors, and she will be hanged in the square as people throw stones at her and scream for justice.

But Miranda doesn’t care.

“I have power inside me,” she whispers—to no one, she thinks. “And I am tired of hiding it. I don’t want to hide it. I shouldn’t have to hide it. It is me, and I am it, and this is how things are supposed to be. Girls are supposed to be wild. Women are not supposed to hide. There should be queens, not kings. I know the old stories. I know of the old country. I know about the old fire and the ancient storms. Why must I pretend that I don’t? Why must I lie? Why must I hide?”

The words spill out of her, held back too long, and the impact of hearing her own voice speaking treason is so tremendous that she begins to sob and laugh at the same time. Exhaustion claims her, and she lays back in the grasses and stares at the sky, knowing she must soon get dressed and return to town. Knowing her father will beat her for bruising the fruit she bought today.

And the wind watches, and is pleased. The invitation has been sent.

“You don’t have to hide,” it whispers to her.

Miranda shoots upright. “Who’s there?” She hadn’t cared, before—but now that she has calmed, the fear of being caught is like a wild animal in her chest. She finds her veil and tries to put it back on, but the wind tears it from her fingers and flings it into the mountains.

And without her veil, even though explaining how she lost it will be worse—much worse—than explaining the ruined fruit, Miranda feels taller, larger, stronger.

“Who’s there?” she demands. “Show yourself.”

“I’m afraid I can’t,” says the wind, “for I have no body. I have only an offer of friendship, and a proposal.”

Miranda’s eyes narrow. “What kind of a proposal? And why do you want to be friends with me?”

“I want to be friends with you,” the wind hisses through the meadow grasses, “because you are wild, like me.”

“I am not wild,” Miranda protests automatically.

The wind snaps at her furiously, flinging dirt into her eyes. “You can’t lie to me. You can lie to the others, but not to me. I know what you really are.”

Miranda licks her lips, though she doesn’t want to appear too interested. What if a shepherd is watching from the trees? A girl, talking to nothing? She would be hanged for madness. “And what is that?” she asks.

“You’re a girl. You’re a wild, wild girl. You have the old fire and the ancient storms in your blood. You have the power to raze mountains and part oceans. You have the power, but they have taken it from you, because they are afraid of what you could do to them. Too many years have passed between now and then, between now and the old world, when women wore the crowns and girls ran free. But it’s time, now.”

The wind sighs across Miranda’s bare legs, comforting her, enticing her. “It’s time now,” the wind continues, “don’t you see? That is my proposal. It’s time to change things. Do you know, you are the first girl in a thousand years to spill her secrets to the wind? It had to be you, coming to me. I cannot do it on my own. That is the way of things. The girl must come to me, and realize who she is—what she is—and then, only then, can I help her.”

The wind is lonely—frustrated and mighty and dangerous. Mischievous. Not entirely trustworthy, perhaps. Miranda can hear these things in its voice. But Miranda isn’t afraid. This is what she has been waiting for, even if she didn’t know it would be exactly this. This is what she has prayed for. This is what she has been secretly thinking during her lessons, while her tutor drones on and on with his watery eyes on her—like she is a bug and he is a bird who might crush her if he decides he is hungry.

“If you tell me what to do,” the wind continues, shishing and shushing across the meadow, “I will do it. No one else can tell the wind what to do but a wild girl. No one else can change things but me—and you.”

“Will it hurt people?” asks Miranda. “Will it hurt people, what we do?”

“Some. Not all, but some. Some hurt is necessary, for the kind of change we need. Don’t you see that, Miranda? Don’t you think it is so?”

Miranda thinks for a long time, sitting there, bare-legged and barefooted in the meadow, until the sun sets and the sky is awash with flame. She will have some serious explaining to do when she gets home. Some girls might throw themselves in the river instead of face their father’s wrath.

But Miranda is not one of them.

And it isn’t like she wants to hurt people, but . . . but . . . haven’t they hurt her? How many hangings has she been forced to attend? How many stones has her father forced her to throw?

Too many.

Miranda’s hands curl into fists, and a spark lights inside her.

“All right,” she tells the wind at last, “all right, I will do it.”

Then she begins the journey back to town, not bothering to find her shoes, not bothering to search for her veil or her parcels. The more steps she takes, the faster she walks, until she is running, racing, tearing down the path to her gleaming city, with fire in her blood and storms in her eyes.

And the wind churns after her, laughing at her heels.

*

The grocer—he’s the one who triggers it.

Unfortunate enough to be nearest the outskirts when Miranda comes running.

Shocked enough to drop his armful of vegetables at the sight of this girl—without her veil, barefoot, her skirts torn.

Foolish enough to seize her arm as she races by, and scold her for her impropriety.

“I’ll ring for the censors,” he shouts. “Have you lost your mind, girl?”

Miranda is used to being grabbed, used to being struck and scolded and ordered about—but that was before, and this is now. Now, she has a wind at her back. Now, her fingers are on fire with something she will no longer contain.

Truly—her fingers are on fire.

The grocer sees the sparks erupting from her hands and releases her, tries to run—but Miranda is too quick for that.

“Go inside him,” she hisses, in a voice that would scandalize her tutor, for it is coarse and lacks any sort of decorum.

And the wind obeys.

It shoots past Miranda, gathering up all her fire, stretching it out from her fingers into the air, down the grocer’s throat, down his nose, up his fingernails, into his eyes.

The power is Miranda’s—old and immense. But the wind takes it to where it needs to be, like an invisible chariot. The wind, who knows Miranda’s secrets. The wind, who, like her, is tired and angry. The wind, who, unlike her, will take much pleasure in the days to come—days of fire and storms and pain.

In truth, it would not take more than this—this one man, this one burst of fire—to change things. It is enough, this one death, to get the attention of Aurestra’s kings.

But Miranda doesn’t know that. And the wind is not going to tell her.

Instead it will race along at her heels, whispering encouragement, as she tears through the city, and the palace, and the calloused flesh of her father’s cruel, meaty fists.

And then what? When all is ash and Miranda’s fire dims, and she understands, exhausted, streaked with strangers’ blood, what she has done?

The wind considers that, for a fleeting moment, as it brings Miranda’s storms crashing through the windows of the censors’ courts—but then, as is the way with wind, as soon as the thought has come, it has gone, and all it knows is its own laughter.

The Knot Inside

There’s a string in the back of my throat. At least that’s what it feels like.

Like there’s something thin and rough, coiled there, waiting.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to swallow my food.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to breathe.

It must be growing.

I think, soon, I may have to try and pull it out.

Whatever it is.

*

I’ve tried to trace the arrival of the string back to an event in my life, and this is the best I could come up with:

The string, I think, must have arrived on Francis’s first day of school.

Francis Eckhart is this girl who moved here from Wisconsin. One of the Midwest states, anyway. She’s got an accent. She has great clothes. She makes decent grades without even trying.

She has beautiful hair.

Out of everything, that’s what I noticed most.

I have terrible hair. It’s this fine, mousy brown mess, and I can’t get it to look anything like it’s supposed to.

The first time I saw Francis, it was in the cafeteria at lunch. She didn’t have anywhere to sit, so I did this dorky wave at her, and she came over and sat down across from me.

She smiled at me and my friends, and we all started talking about Wisconsin and moving in the middle of the school year and how awful that is. Also, movies. And Stephen Parker, who flirts with the lunch lady because he thinks someday she’ll give him an extra piece of pizza for free. She never does.

So we talked. It was nice. It was normal. It was whatever.

But the whole time I couldn’t stop thinking about Francis’s hair. It’s long and golden. Rapunzel hair. Smooth, shiny.

I had this fantasy, in that moment, at the lunch table, about taking a knife and cutting it all off, really close to her scalp, and sewing it onto my own head.

It wouldn’t hurt her or anything. Come on. I’m not violent.

But it was kind of a violent thought, and that surprised me. I’m not violent, I swear.

The thought seemed to come out of nowhere.

It’s just that I have really impossible, mousy brown, very non-Rapunzel hair. Which doesn’t seem very fair. Like, cosmically.

I kept thinking about that all day. How exactly would one sew a head of someone else’s hair onto one’s own scalp?

Hair transfer!

No idea.

But thinking about it got me through an especially boring afternoon of world geography, science labs, and algebra.

I mean, whatever you’ve got to think about to tolerate the school day, right? It’s not like I would actually do that to Francis.

I wish that I could. But I never would.

*

So I got home that night, and that’s when I felt the string.

At first I thought it was just a scratchy throat. Okay, fine. Drink some water, suck on some cough drops, have chicken noodle soup for dinner.

Freak Dad out, just a little. Just for fun. Just for a little bit of pity.

No, Dad. Seriously, it’s okay. (God. So much for fun.) I don’t need to go to the doctor. It’s not strep throat. It’s not the flu. It’s just a cold.

But it wasn’t a cold.

It was the string.

I realize that now.

*

After that, I started to notice things I never paid much attention to before.

Like, for example, I have a decent number of friends, right? I’ve known some of them since I was really little. We pass notes in class, we have sleepovers, all that.

I’d never been unhappy with that before.

But then, maybe a few days after I first felt the string, I noticed how Stephen—he who flirts with lunch ladies—didn’t just flirt with lunch ladies.

He sort of flirted with everyone.

It wasn’t like he liked everyone. Not like that. It’s just he’s the kind of kid who makes friends like other people take breaths.

I started observing him as much as I could without seeming like a freak.

He had this way about him, this way of saying all the right things at all the right times. This way of making jokes that were just the right amount of corny.

I could never be like that.

I always say all the wrong things at the wrong times. My jokes are either too corny or I don’t tell them right and they fall flat as wet paper.

I started imagining that Stephen had this secret component inside him, like a part to a machine, that gave him the ability to do these things. To make friends like it was nothing.

I am an awkward person, there’s no doubt about that.

Stephen is the antithesis of awkward. It’s kind of revolting.

So, this secret component of Stephen’s, this machine part. What if it was something I could extract? What if it was something I could carve out of him like when we carved out the livers of those rats last year in science?

What if I could install it in myself, and become like him, but better? Like him, but me?

I thought this one day, drifting along with everyone down the hall, from lunch to algebra to world geography to gym.

I found myself examining Stephen from afar. Not like I was checking him out or anything like that. Puh-lease.

But more like a doctor might. More like a doctor might look at a person and try to figure out where a disease might have originated, so he could proceed to cut it out.

*

And so it went, on and on.

I kept experiencing these thoughts, these daydreams, that felt . . . wrong. They felt somehow . . . not mine. They came out of nowhere—slicing off Francis’s hair, carving out Stephen’s anti-awkward flirt device.

Stealing Garrett White’s money. (He got such a huge weekly allowance, and for what? For having the luck to be born into a rich family? Give me a break.)

Somehow absorbing Luis Mendoza’s IQ. (Maybe another exercise in carving? But how to get through the skull to the brain without damaging its parts?)

Raiding Donna Beach’s house, stealing her collection of trophies, awards, medals, ribbons. Scratching off her names and replacing them with my own. Scratch, scratch, scratch. With a nail, or a knife. (And you better not come running at me, Donna. You better just let me steal them. I have a nail. I have a knife.)

*

It was that last set of thoughts that made me do it.

That last set of thoughts scared me. I could almost feel the knife in my hands. I could almost see Donna Beach’s terrified blue eyes.

Swipe.

These thoughts, they came out of nowhere.

They came out of a dark nowhere deep inside me. A nowhere that wasn’t mine. At least, it didn’t feel like mine.

So I lay curled up on the bed for a while, my hands clamped over my ears, my eyes squeezed shut, and I cried and whimpered and tried to will the images away.

Like when you’re lying in bed at night and think you hear a movement, see a shadow, feel a breath in your hair, and you know it’s just silly, it’s just your imagination, it’s just your half-awake mind playing tricks.

You can, if you do it just right, convince yourself of that—that nothing’s there, you felt nothing, you heard and saw nothing—and you can fall right back asleep.

So that’s what I lay there trying to do.

But I couldn’t.

No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t keep from thinking these thoughts of knives and cut hair and carved body parts and sweaty money that should have been mine, friends that should have been mine, a body—a beautiful, skinny, blond-haired body—that should have been mine, mine, mine.

No matter how hard I tried, still the thoughts scratched.

Scratch, like a nail across wood.

Scratch, like a blade across a shiny gold medal.

*

So I get up.

There’s a string in the back of my throat.

It must be growing.

I think, although I don’t understand how, that these deep, dark nowhere thoughts have something to do with this thing tangled up at the back of my throat.

So I get up.

I go into the bathroom.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to breathe.

Every day it’s a little bit harder to stop these thoughts from bursting out of me into action.

There’s a string in the back of my throat.

I think, soon, I may have to try and pull it out.

So I get up.

I go into the bathroom, and I lock myself in.

I go into the bathroom, and I lock myself in, and I climb up onto the bathroom sink.

And right there, beneath the glaring lights—four, in a row, gold-rimmed, movie star style! It’s time for my close-up! Dressing room glamour! And I think of that movie star, that actress, and I think of how her perfect megawatt smile would look on my face, and I think of what her long skinny legs would look like on my body, and I think about what it would take to make those things happen.

And right there, beneath the glaring lights, I open my mouth wide, reach back into my mouth with my fingers, find it—Yes! I was right! A string, coarse and thin and coiled!

And I pull.

*

I pull, and I pull.

I pull the string, and it keeps coming, like one of those magic tricks where the guy has colored scarves hidden up his sleeve, only this isn’t funny.

It’s snaking, it’s sliding, it’s snagging its way up my throat, across my tongue, between my teeth.

I stumble off the sink and onto the rug. I am kneeling now, and still pulling.

I keep gagging because it feels like I’m pulling out my own insides.

I want to throw up, but more than that I want this string out.

Something’s on the end of this string. On the other end, deep inside me. I can feel the weight of it tugging.

So I pull, and I pull.

And finally, the rest of it comes loose, a tangle of dark coarse string on the floor.

I sit there. I am gasping, trying to breathe. My throat is sore from the pulling.

You okay in there, sweetie?

Yes, Dad. I’m fine. I just pulled ten feet of string out of my body and it’s sitting on the floor in front of me like a dead thing and I am A-OK.

Then, the string begins to move.

It begins to take a shape.

At first it kind of weaves around like a charmed snake, and it knots and un-knots itself, and it smells like my blood. Like waking up from a nosebleed, in a mess of bloody pillows. Like getting hit in the face with a soccer ball and having blood spurt down your face and down your throat until you’re literally drinking it.

That is what this smells like.

I watch it happen. I should run, maybe, but I seem to have forgotten how to move my legs.

Then the string isn’t a string anymore.

It’s taken the shape of a person, all the details outlined with the string that was inside me, and the insides are blurry, like dirty fluid.

It’s an odd construction, but I still recognize it.

The string has taken the shape of me.

*

“Well?” says the string-me. The ghost-me. The echo-me.

It’s me, I know that somehow. Like, if you saw one of your own pulled teeth in a line-up of other people’s pulled teeth, maybe you’d recognize it. Like that.

It’s me.

But it’s a better me.

This me has long, golden hair. Shiny. Smooth. Rapunzel hair.

This me has a look on her face like she knows just what I want, more than even I do, and she’ll let me have it if I ask nicely.

This me has good skin, clothes that aren’t hand-me-downs, clothes that fit right. This me reeks of money.

This me has an intelligence in her eyes that I can’t look directly at, like the sun.

This me has a dozen gold medals around her neck.

This me has long, skinny legs and a megawatt smile.

This me is all my deep, dark nowhere thoughts come to life. This me is . . . everything.

“Well?” She says it again. She looks me up and down, crosses her arms. “Are you ready?”

“For . . . what?”

“For me to change your life.”

I lick my lips. “How?” But somehow I already know.

She stares at me for a while. Flicks her golden hair over her shoulder. I watch it cascade, and I swear to God there’s a part of me that actually hurts to see something so beautiful—on me.

“I know all the things you’ve been thinking,” she says. She kind of sings it.

I blush. “That’s impossible. You’re not—”

“Real?” She laughs. God, to have a laugh like that! Mine is this really unfortunate bray. And yet . . . and yet, in that perfect laugh of hers, I can hear, faintly, the sound of my own laugh.

My own laugh, but better.

“I promise you I’m real,” she says. “I’m real because you made me real.”

“How did I do that?”

She pauses, tilts her head. Her eyes flash. “By wanting.”

The word drags out of her mouth like the string had dragged out of mine.

“Wanting . . . what?” I say.

But she just stares at me.

“Wanting . . .” I pause, swallow. My throat is so raw it’s like swallowing gravel.

“Wanting to be like you,” I say. “Wanting to be beautiful. To be smart.”

“To have trophies and medals,” she hisses, taking my hand. “To have money and long, long legs.”

“To be . . .”

“More.”

“To want . . .”

“More.”

She says the word over and over. She combs my hair with her fingers, and already my hopeless lank droopy hair feels more beautiful. She runs her fingers across my scalp, and already my brain feels sharper, more focused.

It feels good.

It feels fantastic.

I want more of this.

“More,” I whisper to her.

And then I take her hand.

And it’s at this moment, when her cold, scratchy hand folds around mine—when I feel that familiar coarseness of the string that was in my throat and now forms the outline of her cold, scratchy, made-of-thorns hand—that I see her close enough to understand.

I see how her scalp bleeds in a patchwork, where she has threaded these long blond locks into her skin.

I see how her perfect, glowing skin bears stitches—her fingers, sewn into place here. Her long, long legs, attached with thick black thread there.

I see how her eyes sit in her face funny. I see the tiny stitchings around the sockets.

I see how the medals around her neck are made not of gold, but of skin—stretched tight, gold paint lazily slapped on top.

I hear how her words aren’t words, but thousands of tiny buzzing sounds, held together in the shape of words by this mouth full of teeth that have been stitched into her gaping gums.

This close, I no longer see myself in this creature.

I see what she truly is.

She is my deep, dark nowhere thoughts.

She brought them to me, she is them, and I helped her out, into the world, into my bathroom, holding my hand, stroking my hair.

She whispers of the great, terrible things we will do together.

How I will never want again.

This close, I understand what I have done. What I will do.

I try to pull away.

But it’s too late.

She is unlocking the door.

Her hand is around mine.

She has me.

February is the Month of Envy

Dear readers,

As much as we Curators don’t quite want to believe it, time has continued on, as it tends to do, and we now find ourselves in the month of February.

February, I think you’ll agree, is a funny sort of month. It’s shorter than all the others, for one (not that there’s anything wrong with being short), and it’s when the groundhog pops up and does or doesn’t see his shadow (a strange custom, if there ever was one), and it’s that last stretch of winter when it seems like the world will never be warm again.

It’s also a month in which people celebrate love, or don’t, or wish they could, or are glad they don’t have to, or think it odd that a day originally meant to honor a martyred saint has evolved into a day on which we give each other boxed chocolates and cheesy greeting cards.

And let’s think about love for a moment. Last February, when the Cabinet was newly opened, we Curators wrote about love in its many odd forms–between a woman and a child that isn’t hers; between a girl and her doll; the love between friends, and the love between the living and the dead.

Now, a year later, we write about a thing that often comes along with love, or interferes with love, or pollutes it, like a burr stuck to the shadowy underside of something that should be beautiful, if you do it right. This year, we write about something that doesn’t even have to be associated with love at all; no, this thing comes in all shapes and sizes.

This month, we write about envy.

A person might envy someone their happiness, their success, their magical abilities, the love they share with their boyfriend, girlfriend, sister, parent.

A person might envy anything, big or small, good or evil.

What will the characters in this month’s stories envy?

You’ll just have to wait and see for yourself.

Teasingly,

Your Curators