Knives

“Yabba, where’re my boots?”

The girl stood in the dark of the hovel and raged. She was tiny. Her knees stuck out like knobby fists, and her nose ran, and her fingers were cracked with dirt and cold. Not even the wind—when it came howling through the chinks in the hovel’s door—could stir the nest of hair on her head, so thick were the knots and tangles. “Where are they?”

Yabba sat in the corner and scowled. He was whittling furiously at a piece of wood.

“Where are they?” the girl snapped again. “What’d you do with them?”

Yabba nicked his finger and hissed, sucking the blood. He looked at the girl. Then his lips curled back. “I sold ’em. Needed the coin.”

The girl let out a screech and flew at him. She’d scratched him halfway across his face before he could even shout.

“You sold ’em?” she screamed. “You sold my boots?”

Yabba regained his balance and threw the girl across the hovel. She crashed into the wall and fell, a heap of rags.

“To the tinker,” he said, wiping his face. “Out back of Olga’s.” He set back to whittling the wood, breathing hard. “Go get ’em if you want ’em.”

The girl sat up. There was blood on her head, but she didn’t seem to notice it. “Those were my boots,” she said, quieter now. “Mam gave them to me ‘fore she left. They were mine, Yabba.” Her eyes were beginning to quiver, glistening in the light of a little cook-fire.

“Well, now they’re the tinker’s,” said Yabba. “And you can just shut up about Mam. She weren’t your Mam any more ‘n she was mine. Go to sleep, and tomorrow you get something valuable, you hear? Something we can use, so that I don’t have go out and sell your grotty boots. Lace, or red berries, or something fancy. I’m going to need it.”

* * *

The girl came back the next day with a bundle of twigs, green and uneven, torn from the shrubs beyond the river-fork.

“That don’t look like lace to me,” Yabba said when he saw it. “What else?”

“Nothing,” said the girl. Her teeth were gritted, but she was not as wild as usual. She had gone rather quiet. “Twigs was all I found. That’s all there was today.”

For a moment Yabba stared at her, as if he couldn’t understand. Then he said, “And what d’you expect me to do with twigs?” His black hair was in his face, sticking to his forehead.

“You could sell ’em,” the girl said. “I don’t know. It’s all I got this time.” The girl wouldn’t look at him.

Yabba threw her out the door and she slept that night under the drooping thatch, her feet in the cold rain. When morning came, she ran away up the hill on the other side of the town and got a knife from under the tree that grew there.

* * *

The girl brought the knife back to the hovel. It was a very fine knife. It had a manticore in red carnelian on its hilt and a sheath of finest leather.

“Yabba!” she shouted, and pounded on the door. “Yabba, I have something! Lemme in! Lemme in, or you can’t have it.”

Yabba opened the door. He took the knife and looked it over. “Should do,” he said. “No more of this twig stuff, now, or you’ll be staying outside permanent-like.” Then he left, and he didn’t come back for a whole day and night.

* * *

Yabba came back with a black eye and two yellow teeth in the palm of his hand.

“They didn’t want it!” he screamed. “They didn’t want your stupid knife. ‘Where’d you get a knife like that?’ they said. ‘Ain’t no place we can sell that knife without getting hanged,’ they said. I want coin! Silver and gold, or I’ll throw you out!” He hurled the knife into the dirt at the girl’s feet. Then he stormed away, slamming the door so hard the whole hut shivered.

The girl picked up the knife and folded it gently into the shreds of her dress.

* * *

Yabba didn’t come back to the hovel for a week. When he did, he wanted coin again. The girl hadn’t got anything. She hadn’t left the house, though she didn’t tell Yabba that. She offered Yabba the knife again, but Yabba just spat. He was afraid, then angry, turning circles and growling like a cornered dog.

“What now? What do I do now? You always get something. A pair of gloves or some honey or lard or something. Now what am I ‘spected to do?”

“I want my boots back, Yabba,” the girl said. Her eyes were on the watery broth she was stirring.

Yabba shouted, going hoarse about the money he needed to pay off some people. The girl kept stirring. Her hand was tight around the wooden spoon.

“Those were my boots,” she kept saying. “Those were my boots, Yabba, and Mam gave them to me and I want them back. I asked at Olga’s. The tinker you sold them to, he’s not there no more.”

“Course he’s not there!” Yabba shouted, before he got really mad. “It’s been a fortnight. He’ll be halfway to the moon by now.”

* * *

The girl knelt on a hill under a solitary tree. A heap of knives lay against its roots. The lower ones were black, gnawed-upon by damp, but the ones close to the top still glinted. They were all very fine, with elaborate sigils in the likenesses of dragons and hens and manticores.

“I got another one for you, Mam. You listenin’? I got another one.”

The girl laid a knife on the top of the pile. It had a bit of dirt on its tip. Then the girl rested her head on her knees and stayed that way until long after the sun had gone down and the wind blew sharp and cold over the back of the hill.

* * *

It was morning when the girl made her way through the town toward the hovel. It had rained during the night, and the day was cold and drizzling. Halfway down the street, in front of the church, she came upon some townspeople, huddled together. They were very silent, looking at something on the ground.

“What is it?” the girl asked, edging up to an old woman who was standing a little apart from the others. The woman looked at her a moment, but said nothing. The girl walked around to the other side of the huddle.

Something was lying on the ground. All she could see of it were the bare feet, white and swollen against the black mud.

“Who is it?” she whispered. “Who’s that on the ground?”

“A tinker,” one of the men said, before going back to staring.

“From up North,” said another.

“No great loss,” said a third. “But for the way it was done. Dreadful. Like some sort of beast, only bigger. Not like anything around here. Not like wolves.”

The girl didn’t wait with the townsfolk. She ran back to the hovel, feet sliding in the mud.

* * *

A woman hurries about the hovel, rushing from corner to corner, wrapping a heel of bread, lighting a lantern. She tries to be quiet, but she is not quiet enough. A girl wakes from the straw in the corner.

“Mam?” she asks. Her voice is scratchy with sleep. “What you doin’, Mam?”

The woman goes very still, her back to the girl. She closes her eyes. Her face is worn and thin.

“I have to leave for a while,” she says. Her hand closes around the warm glass of the lantern, trying to block out the light, but the girl is already standing up in her little bed, shaking.

“Why you going, Mam? Why you taking all those things?”

The woman’s skin is like leather, hardened from winters and summers and falls. She turns and reaches out a finger, brushing it over the child’s face.“Now, deary. No crying. You’ll see Mam again. You’ll see me one day.”

“Don’t leave, Mam. Don’t leave me with Yabba, I don’t like Yabba!”

But the woman is already turning. She’s at the door, heaving her sack. “I have to,” she whispers. “I’m ten kinds of dead if I stay.”

“Why?” the girl cries, and it’s a piercing sound, like a whistle. She looks as if she wants to follow the woman, but she’s still rooted to the bed of straw.

“He’s after me,” the woman says. She pulls up her shawl, black and crimson, shadowing her face. “He’s after me and he won’t ever stop. I stole something from him, see. Years ago. I thought it would be good and help me, but it wasn’t good, and he knows my scent. He’s been chasing and chasing me all these years, and he’s close now. So close. But he won’t have those boots. He won’t have them back. You keep them, all right? You keep them and you use them.”

“Mam!” the girl says, shifting from foot to foot on the bed. “I’ll help you, Mam! He won’t catch you, I’ll take care of you!”

The woman half turns in the doorway, a dark shape against the blue night. The girl can’t see her expression—a sad smile on cracked lips. “Oh, deary. Nothing can save me now. Nothing but a good sharp knife.”

* * *

That night the girl woke in a sweat. “Mam?“ she called.

“Shut up.” Yabba turned over in the thick blackness. “Go to sleep.”

The girl eased up onto his elbows. Her shoulders were trembling. “Yabba?” she said, after several minutes. The word stuck in the dark like a tuft of wool. “Yabba, why’d Mam go?”

“I said, shut up.”

“Why’d she leave, Yabba?”

Yabba lurched up and dragged the younger girl over by the scruff of her neck.

“She weren’t our Mam! She weren’t nothing but a witch, you hear? A good-for-nothing witch. The townsfolk say she was troll’s wife ‘for she ran, and only witches make troll wives. Now shut up about it! I can’t take this no more. I can’t take your stupid talk. Tomorrow you get me something good like you used to, or I’ll burn this place down and run away and you can go house to house and see how they like you there.”

* * *

They found her the next day, face-down in the mud, a half-mile out of town. Something had attacked her on the road, torn her throat out. A lantern lay by her side, cracked open, oil dripping into the wagon ruts. It mingled with the blood, black and crimson.

There was no funeral. A group of townsfolk carried the body up the hill and dug a grave under the yew tree. No one came to mourn. Only a young girl was there, watching as the dirt rustled onto the white, white face.

* * *

Two days later, a constable stood at the door of the hovel, black boots in a mirror puddle, cape billowing in the drizzle.

“No use hiding in there, girl. There’s a town-full of witnesses seen you break into the Strevlov’s house yesterday.”

Yabba stood in the back, cowering. He shoved the girl forward. The girl looked up, her eyes huge.

“Why’d you do it?” the constable asked. “I know why you took the money, but why all those knives? You must have known you wouldn’t get away with selling them here.”

The girl picked herself up, and not looking at the constable. “I couldn’t get ’em no other way,” she said. Her voice was soft. “I had to get something, and I can’t walk far no more.”

“She’s crazy,” Yabba growled, stepping forward and then back again. “Go lock ‘er up. I can’t stand it.”

“You shut your mouth,” the constable barked. He didn’t take his eyes from the girl. His eyes were hard, but not all the way to the bottom. “You’re in a heap of trouble, my girl. Come. You’ll not be staying here.”

* * *

The girl lay in a dank cell. Wind whistled through the cracks in the gray daub-and-mottle walls. Water dripped from the ceiling. An iron bucket caught it with little plinks.

After a day or so, a key ground in the lock. The constable was there, boots freshly blacked.

“We found your stash, child. Up on the hill by old Sheema’s grave.”

The girl said nothing.

“How’d you get all those knives? From halfway ‘cross the country, some of them. And the one on top––from Lord Naryeshkin’s own larder. His castle’s seven leagues from here!”

The girl looked up at the man, then through him as if he were made of glass. She was seeing the tree, and Mam, and Mam was smiling at her, waving her on.

“It weren’t so far,” she said quietly. “I had boots then.”

Jack Shadow

. This story based on Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Shadow.”

The shadow slipped through the night, hid from the sun, stretched out every morning and evening. Through towns and along roads that stretched for miles, the shadow slid.

You might not think that a shadow would have a name, but this one did, unpronounceable though it certainly was. It sounded a little like a snake slithering over moss, a little like fairy tears hitting the surface of a river.

But we…we shall call him Jack, just for now, because it is easier than snake-slithers and fairy tears, and this story is quite difficult enough to tell.

Jack was hunting. He had been for many years, and hoped it would not take much longer. A shadow, you see, needs a person, and this was the one thing he did not currently have.

Over his time, there had been many, tried on as one might test a new suit for a good fit. The last one, well, he had been nearly right, nearly perfect, but in the end that had made him very wrong.

A city loomed ahead; surely he would find what he was looking for in there, with so many people to choose from. Glass towers stood tall among small houses, reminding him of palaces. Of the days of dragons and kings.

Yes, my friends, our Jack the Shadow is that old, and then some.

I do suppose that now, as Jack edges into the city, mingling with all the normal shadows of sunset, is a good time to warn you that if Jack ever comes seeking to become your shadow, you must run. Run far and fast and do not look back. I only wish I had been able to warn the others, but I, unlike our Jack, am capable of regret.

Then again, you might well never know if Jack, or one like him, has begun to follow, a dark, sharp-edged blade of a thing.

He moved along the bustling streets, alert, careful, almost disappearing behind buildings as the sun dropped lower and lower in the sky. Turning a corner, he entered a quiet neighborhood full of tall, snow-white houses and old trees that spread leafy branches overhead.

This was promising. And you of course will know that when I say promising I mean dreadful, but to Jack, it was very promising indeed.

Up ahead, on the lawn of a large house on the next corner, a young boy kicked a ball, always reaching it just a second before his shadow—a real shadow—did. Jack crept up toward the house.

“Sam!” came a voice from within. “Time to wash up for dinner!”

“Coming!” he called back. Sam’s real shadow made to trail him into the house, but Jack caught it and held it back.

“We won’t be needing you anymore,” he said as the front door closed. Sam’s shadow turned around. It trembled in the breeze.

“No,” it said. “He’s a perfectly good boy and I won’t let you hurt him!”

“Hmmm,” said Jack the Shadow. “Why would you think I would hurt him?”

“I’ve heard of you,” it answered, shaking harder as the wind blew. “I heard what you did to that poor man, following him around for years and years, sucking the very life out of him until he was more of a shadow than you were!”

Jack laughed. It frightened the birds from the trees. He had been particularly proud of that one, but in the end, the man had not been the perfect fit. He had not wanted to become Jack’s shadow, and so there was only one thing that could be done.

“You killed him, and I won’t let you do it to Sam.”

“I do not think,” Jack said, “that you have a choice.” Swiftly, he plucked a strand of cobweb from a nearby bush and with it he slit the other shadow’s throat.

Now, you and I know that you could not ordinarily do such a thing with a cobweb, but shadows are not ordinary, and Jack was extraordinary, in the strictest sense of that word. Shadows do not play by the rules, and so the dead shadow shattered into a thousand tiny, black-winged moths and flew away.

The other shadow had been right about one thing. In fact, he had been right about everything, including what Jack did to the last one, but it was certainly right that Sam was a perfectly nice boy. Jack sat at the table while Sam ate, hid in a corner while he did every last bit of his schoolwork, and listened from the closet as his father read to him each night. He followed Sam to school and kicked a ball around the grass with him before dinner.

Jack was sure it was a perfect fit, that it was simply a matter of time.

Sam grew older, always a good boy, but taller, thinner, paler, his veins blue beneath his skin. His mother took him to the doctor, who said Sam was perfectly healthy, but perhaps a growing boy needed more sleep.

Jack hid under the chair in the doctor’s office and laughed. Goosebumps broke out over Sam’s skin.

“Sam,” Jack said that night, when the lights were out, the house quiet as a tomb.

“Who said that?” Sam asked, sitting bolt upright in bed.

“I’m your shadow.” Jack slid from the bed, over to the patch of moonlight on the floor. He stretched high as the ceiling, leaning over the boy in the bed. “You’ve been very good, but now it is time.”

“T-time for what?” Sam blinked, as if he was unsure whether he was truly awake.

“You are not dreaming,” said Jack. “It is time. I have followed you since you were young, Sam. I have done everything you asked of me, and now you must do what I ask of you. It is your turn to become my shadow.”

“I am dreaming,” Sam replied. “You aren’t real.” He lay back down and closed his eyes, turning his face into the pillow. Jack shook with rage, his whole thin, flat body shivering like the beat of a thousand moth wings. He slipped from the room, down the stairs, to the kitchen drawer where all the sharp knives were kept. Cobwebs did not work on people, and people follow the rules.

I cannot bear what happened next, just cannot bear it. You can imagine, you can close your eyes and picture it, if you so choose, though I wouldn’t choose to. Please forgive me if I don’t tell you every word, describe every drop of blood as it bloomed on the pillow.

I told you already that I wish I could have warned the others, and I only hope this has been enough of a warning for you. And so, rather than go through every last, horrible detail, I will instead ask you to do something for me. Go outside, stand in the sun. Close your eyes and feel it warm your face.

Open them again. Look around.

Is that truly your shadow?

Are you sure?

The Shoes that were Danced to Pieces

Our father is a bad man. We hate him.

He has twelve daughters, and I am the youngest. He is the king, but when he dies, none of us shall rule. He laughs at the idea. Although he has twelve daughters like twelve strong trees, like a sheaf of wheat; although we are some of us brilliant, some of us strong and fast, and some of us tenderly kind, and some of us able to talk a flock of birds or people into following wherever she leads—despite all that, he laughs at the idea of a woman ruler.

“I’d more likely leave my kingdom to my dogs,” he says.

When my oldest sister tries to lay the case for fairness, or for sanity—that he could choose one of us other than her, even, or that perhaps we could rule together, lend each of our separate strengths to lead the kingdom to a new happiness and peace (for it has seen little of either under his clumsy, brutal rule)—our father mocks her, says in a high lisping voice (and she doesn’t lisp, and her voice is low and cool), “Oh Daddy, pwease, I want to wear the pwetty crown, it will show off my pwetty shining eyes!”

We hate him. My eldest sister hates him most of all. He would never give her the tutors she begged for, so she has learned and studied in secret, all her life. She is the cleverest of us all.

Father intended to give the rulership to some stupid, brutal boy he will choose to marry one of us. But we had other plans. We said: We’ll never be married, never. Though we will not rule, we will keep our own freedom until we die.

One morning, as we lay in our twelve beds, my sister Rêve sat up straight and fast. Her eyes were shining and wild. “I have had one of my dreams,” she said. Rêve is a great dreamer, and knows how to dream things true. But all she would say was that that night, after the king our father went to bed, we should all dress in our favorite, our loveliest, our wildest dresses, and wear our dancing shoes,

We did as she said. “Now see what I dreamed,” said Rêve. She knocked three times on the wooden headboard of our eldest sister’s bed: knock, knock, knock.

For a moment, nothing happened. And then—oh, and then—the bed sank away, as if sinking into a great black lake. And beneath the bed were stone stairs, going down, down, down.

So down the stairs we went, in our clothes of ebony silk, of cherry-wine velvet, of lilac lace. Our soft dancing shoes made no noise at all on the stone steps.

At the bottom of the staircase, we entered a forest where the trees were made of filigreed silver.

Next we came through another forest, where the trees were shaped of shimmering gold, delicate gold leaves trembling as we stirred the air around them in our passing. The gold made the air feel warm.

Then we moved through a third forest, whose trees were cut from diamond. Each twig and leaf glittered hard and bright around us, and in that forest I felt as cold as if the trees were carved of ice.

We emerged onto the shore of a vast black lake, a lake that mirrored a vast black sky, so both seemed crowded with diamond stars, and no moon at all. Floating before us were twelve boats, each a different color, the colors darkened and subdued under the pale stars.

In each boat sat a young man, each quite different, skin dark or fair, but each with the same mournful smile and something ghostly around the eyes and mouth.

I chose the ghost-boy whose boat might have been sky-blue, in the light. When he helped me in, his hand was as cold as the diamond forest.

The ghost boys rowed us in perfect silence to an island where a crystal castle stood. Warm lights moved and glowed inside the castle, like fire caught behind glass.

Inside the castle was an orchestra made up of forest animals—a grave jay with a tiny violin, and a white stag with a cello, and a smiling fox on a stool with a clarinet—oh so many of them, many more. And their music was wild, and it was mournful, too. The music had fire and rage underneath it to match our fire and rage, and it made us want to do nothing but dance.

So dance we did with our cold and ghosty boys, we danced out our rage all the wild night, as the violin-bearing birds swirled above our heads, the fiery lights swirling too as we swirled in the dance, our heads flung back, our feet mad beneath us.

So dance we did with our cold and ghosty boys, we danced out our rage all the wild night, as the violin-bearing birds swirled above our heads, the fiery lights swirling too as we swirled in the dance, our heads flung back, our feet mad beneath us.

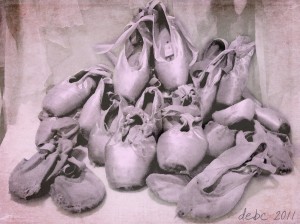

When the eastern horizon began to soften, the boys rowed us back to the edge of the lake, and we walked through the icy diamond forest, and the shimmering gold one, and the delicate silver one, and back up the stairs to our room. On the floor beside each bed, we left our shoes in shreds and pieces

The next morning, the wretched maid told our father about our shoes. He demanded to know what had happened. But we were half dead from our long night, and we said nothing at all. Even my sister who always talks back just looked at him, her face pale and empty, and turned away.

He ordered that we must be kept shod, and left. New shoes were brought that afternoon.

The next night, we went dancing again, we danced our anger, and the next and the next and the next and the next. Every morning, our new shoes lay in shreds on the floor beside each bed; every morning, our father would shout and argue and insult us.

But we were turning half-ghost ourselves by day, with all our life in the night, and we only looked at him from dark-circled eyes and yawned.

Our father made an announcement to the kingdom. Any man who could solve the mystery, he would marry off to one of us, and make his heir. But if the man tried for three nights and could not solve the mystery, he would lose his head.

“That should motivate them,” said our father. His cruelty, his cruelty.

A prince from a far land came to try. Father gave these him the room beside ours, and left the door between open, which shamed and angered us. But my clever eldest sister made a potion, and put it in fine wine, and offered it to the prince with falsely loving words.

The potion made him sleep all night, and we were left to our raging revels. He slept through three nights, bewildered each morning at how it had happened.

On the third morning, my father had his head chopped off with an axe.

My heart wavered at this, for he had not seemed a bad man, only a hopeful and arrogant one. But my eldest sister, whose rage was greater, laughed. “It is what he deserves,” she said. “It is what they all deserve.”

Then she added, so perhaps her heart was not quite eaten with anger: “Anyway, it is father who kills them, not I.”

More princes came. More princes tried. More lost their heads. My eldest sister’s laugh became uglier and too much like my father’s.

Then no men came for a long time. We danced out our rage every night. Every morning we grew paler, but our eyes were bright and hot inside their dark circles. My father’s anger grew, because something was happening that he could not control.

But that his daughters grew into ghosts before his eyes: that worried him not at all.

After a year of the dancing, a new man came to try. He was different from the others, older, and no prince at all, but a common soldier who had been wounded in the leg, so that he limped badly, and could fight no more. He told us that he had met a strange old woman and shared his food with her, and she had repaid him by telling him of our father’s offer, “as well as with advice, and a small gift.”

I did not like to hear that, for there is great power in the gratitude of strange old women.

My father said, “I hope her gift was an iron neck,” and laughed.

When my eldest sister brought this new man the doctored wine and false words, he watched her out of dark eyes, and I thought I saw something like pity in them, which confused and frightened me. But he drank—or we thought he drank. And when the night came, he slept—or we thought he slept.

And yet when we slipped down the stairs that night, I was sure I heard a heavy, uneven gait behind me.

But when I turned, I saw nothing at all.

When we passed through the silver forest, I was sure I heard the limping steps behind me still. And I did hear, I know I heard, a sudden crack, like the snapping of a branch. I looked wildly around. “It was probably an animal,” said my sister Tendresse. “Calm yourself, calm yourself.”

So I put the limping, swinging, invisible step out of my mind, and out of my hearing, and found my ghosty boy, and danced my raging dance all night in the fiery crystal palace.

The next morning, the soldier said, as they all had said, “But I don’t understand how I could have fallen asleep.” I felt better. My imagination must have been playing tricks on me—my imagination, and perhaps my too great respect for strange old women.

In the silver forest that night, when I heard the limping, broken steps behind me, I said to myself firmly: “Your imagination.”

And at the crack of the branch in the golden forest, I said to myself, “An animal.”

Still, I could not throw myself into the black lake of our dance as deeply as usual.

In the morning, the soldier said, “Only one more night! It certainly doesn’t look good for me.” So I thought it must be all right after all.

And yet that third night, the heavy, limping gait behind me felt like the gait of Death. The crack of the branch in the diamond forest thrust a shard of ice into my heart.

And as I danced, I swear as I danced with my cold, mournful, ghosty boy, I felt something touch my arm here and there, something I could not see, as if that Death walked among us in the dance.

That morning, my father came with guards to take the soldier away to be beheaded. They found him sitting politely at the edge of his neatly-made bed, holding in his lap a silver branch, a golden branch, and a diamond one. As we watched from our room in despair, he told the whole story of what we did each night, and held up the branches one at a time for proof.

The king our father laughed and laughed, and clapped the soldier too hard on his back, and jeered at us. “They want to rule the kingdom, and yet they spend their nights giggling and dancing, like the empty heads they are.”

(But he did not know, had never seen, our raging, raging dance.)

The soldier said nothing. My father stopped laughing and said, “Then take whichever you want for a wife—Bellaluna is the prettiest by far—and I’ll set you up in a castle, and then you can wait for me to die, which I hope is a long damn wait.” He walked out, the guards behind him.

The soldier turned to us with his dark, opaque eyes. He said, “I think you are all quite beautiful, and much too beautiful for a man like me. Also, I will not take or choose, as if you were toys in a shop; but I will ask, and I will offer my pledge and my faith and my respect.”

He turned to my eldest sister. “I am no longer a boy, and I wish a wife who is my equal or better in wisdom. I have been watching you for three nights, and I believe that is you. I will need your wisdom to help me make this land a more peaceful place, for I have had enough of fighting. If you will have me, I will make you my queen and co-ruler, and we will heal the kingdom together. You do not need to give me your answer now.”

And he limped away to be shown his new castle.

I watched my eldest sister that night, over the ten narrow beds of my sleeping sisters between us. She lay back with her hands behind her head and her eyes wide open, considering.

In the morning she said to us, “I do not know how to give him my trust, but I am going to give him my trust anyway. My anger has danced through too many pairs of shoes. He is a new man, and I will try a new way.”

So the banns were made and the wedding held, with great pomp and many white horses and silver lace and bells. In the following weeks we visited them at their castle, and we saw a new way between a man and a woman, that we had never conceived of before.

One by one, with our father’s shrugged permission, we moved to the new castle to live. My sister has filled it with books and art and mathematical instruments, and everything our father ever denied us. We sleep well at night, and we have lost our ghostly look, and live in the world around us.

Our father is a bad man. We hate our father.

But one day our father will die. And together with this wounded man, we we will make a new and better kingdom.

Once our father dies.

The Sandman Cometh

A note from your Curators: Dear readers, we apologize that we neglected to post our usual introductory post at the beginning of this week, announcing the theme for this month’s stories. But you see, we have recently had great reason to celebrate, as all four of us met a particularly important deadline for a particularly precious project (that may or may not have something to do with this website you are now reading). And after we met said important deadline, we were in such a state of jubilation that apparently our brains melted and dripped out our ears, leaving us with nothing to govern our common sense but the copious amounts of celebratory cake we consumed.

So, we hope you’ll forgive our forgetfulness — and the tardiness of today’s story — and that you’ll enjoy August’s month of stories, all of which are re-tellings of fairy tales.

Curator Legrand’s story, which you’ll see below, is a re-telling of Hans Christian Andersen’s “Ole Lukøje,” which Curator Legrand thought was a very odd story indeed, and which she might have made even more odd in her re-telling (but neither version is as odd as the adventure during which she was first told the tale).

*

When Harvey goes to bed on Saturday night, his heart is black and hot. In general, he’s a good kid, but he’s suffered one too many indignities today, and thirteen-year-old boys have very little patience to begin with.

First of all, there’s the matter of the dolls. His eight-year-old sister Jessie left her dolls all over the floor after a morning of manic play with her friends from next door. Harvey stepped on them and tripped over them one too many times, and finally lost his temper and kicked one of them into the wall. Out of all the other soft, unbreakable dolls well within reach of his foot, he happened to kick the one with the porcelain face. It shattered, and Jessie’s been an inconsolable mess all day.

Secondly, there’s the matter of his parents. Did they reprimand Jessie for leaving her toys strewn about so irresponsibly? No, they didn’t. All they did was punish Harvey for committing the understandable and relatively minor crime of kicking a doll into a wall. The unfairness of it makes Harvey’s insides seethe.

And that leads to the third thing, which was Harvey not being able to go to the movies tonight with Dennis and Jordan and Enrique and Enrique’s dad, who is far cooler than Harvey’s dad will ever be. Harvey can’t go because he’s grounded. He’s grounded because he reacted like any sane person would after stepping on dolls that his little sister refuses to clean up.

There is no justice in the world tonight. That’s one of the primary thoughts on Harvey’s mind as he falls into a tempestuous sleep.

The other thought is this: “I hate them. I hate all three of them. I want to wake up in the morning and have the house to myself so they can’t annoy me ever again.”

(Oh, dear.)

*

Harvey wakes up in the morning to a blissfully quiet house. In fact, at first he thinks he might have woken up in the wrong house somehow, even though that makes no sense. He doesn’t hear his sister running around singing songs, he doesn’t hear his father banging dishes and pans around the kitchen, and he doesn’t hear his mother’s shows blaring on the television.

He falls back asleep, fantasizing that they’ve all decided to have mercy on him and spare him the chore of Sunday errands. He decides that when he wakes up in a couple of hours, he’ll clean the kitchen so that maybe his parents will lessen his punishment. He figures they’ll return well into the afternoon.

They don’t.

*

It’s been a long day for Harvey. He doesn’t understand where his family has gone. At first it’s wonderful, having the house to himself. He is able to clean the kitchen like a good son would do, and even has time after that to play some video games without Jessie running through the living room asking if she can play too.

He also has time to do his homework. And microwave himself a frozen dinner. And shoot hoops on the driveway after dark on a school night. It is at this point he remembers to look in the garage and realizes that his parents and Jessie haven’t gone to run errands—unless they’ve gone on foot, that is, which is unlikely.

Both cars are still parked in the garage.

*

Harvey is not sleeping well.

Before going to bed, he tried calling some friends of his parents, and also some of Jessie’s friends, to see if anyone knew where they had gone—but the phone didn’t work. That was odd; Harvey checked to make sure it was plugged in, and it was. But it wouldn’t dial a single number. Harvey searched for his parents’ cell phones and tried them, but they didn’t work either.

The television played nothing but static. Videos game worked, but not the television. The computer wouldn’t connect to the Internet. And, as Henry lay there before bed trying to quiet his mind, he realized with a creeping sense of dread that when he had been outside shooting hoops earlier, he hadn’t seen a single other living thing on his street—not a person, not a bird, not the DeRosarios’ fat cat.

But now Harvey is asleep, tossing and turning as the remnants of these worries stew in his mind. He doesn’t see the man enter his room, quiet as shadow. The man is tall and thin and dark, with a crisp black suit and a spotless black umbrella. He leans on the umbrella and watches Harvey for a long time. He is smiling and waiting for Harvey to wake up.

*

When Harvey does wake up, it is in the middle of the night, and the first thing he sees is the man at his door, still and slender.

Harvey screams, and the man lets him. The man looks bored.

When Harvey is done screaming, the man says, “Have you finished?”

The question takes Harvey quite aback. He replies, “I guess.”

“Good.” The man approaches, his coattails trailing behind him like long black tongues. “I’ll make this simple. I have your family, and I’ll only bring them back if you do exactly as I say.”

Harvey is at first dumbstruck and then outraged. Remorse floods through him like a sick, cold tidal wave, and the man watching him seems to shudder, like he can feel Harvey’s emotion and finds it delicious.

“What do you mean you have them?” Harvey demands. “Where are they? And who are you?”

“I can’t tell you where they are. As for your second question, I have many names. I am Morpheus, I am Ole Lukøje, I am the Bringer of Dreams. You may call me the Sandman.”

With that, the Sandman bows. He cuts the air like a black scythe.

Harvey is fairly practical for a thirteen-year-old boy. He knows that such things as Sandmen don’t exist. And yet here is the Sandman, bowing before him. And here is his empty house, and here is the phone and the computer and the television that don’t work. And here is his empty street.

He balls his fists into his bedsheets. “You have my parents, and my sister.”

The Sandman inclines his head. “As I said.”

“Why?”

“Because I need your help.” A small smile curls across his face. “And now, so do they.”

Harvey draws a deep breath. He is terrified; he has never been especially brave. He is the boy who stands on the bank of the creek and watches the other boys swing on the rope into the water.

“What do I have to do?”

The Sandman takes a vial from his pocket and dips a gloved finger into it. “You must complete for me six tasks. If you succeed . . . ” He smears a grainy, rank-smelling tar over Harvey’s eyelids, sealing them shut. “ . . . you may be able to save your family.”

Harvey falls back onto the bed, as heavy and cold as a stone. A shiny substance plugs up his ears and mouth and nose and eyes. Still, though, his eyelids flutter. He is dreaming.

The Sandman settles onto the foot of Harvey’s bed, soft and sleek as a cat. He waits.

*

Harvey awakes in a jungle.

The air is ripe with the smells of rot and sweaty animal fur and tropical flowers. The air is so steamy that Harvey finds it difficult to breathe. He holds in his hand a sealed envelope, addressed in an immaculate hand to The One Who Waits.

A breath wafts across Harvey’s neck. He whirls, but no one is there. He feels cold, ghostly fingers on his shoulders. He slaps them away, but ends up only slapping himself.

Stop slapping yourself and listen to me, says the Sandman’s voice, deep inside Harvey’s head. With every word, that same cold breath caresses Harvey’s neck. This is your first task: Deliver this letter to The One Who Waits, who lives at the other end of the jungle. Do not stop for anything. Do not eat the fruit.

Then, just like that, the Sandman’s presence disappears. Harvey is alone.

None of this makes sense, but the letter in Harvey’s hand feels real enough, so he figures he should go along with this, just in case. Anyway, delivering a letter doesn’t sound so hard, and he’s not hungry, so avoiding fruit won’t be a problem.

But then Harvey begins to walk. The way is overgrown and dripping with moisture, and he notices that the branches hang heavy with fruit—at first just normal fruit like bananas and oranges, and although they are brightly colored, they don’t particularly tempt Henry. But then he sees mangoes and passion fruit, and kiwi and pineapples, and soon Henry is pushing aside piles of grapes and bushes laden with strawberries, and countless other unfamiliar fruits in yellows and blues and purples that brush against his face and arms. Their soft, fuzzy skins tickle his cheeks.

Their scents twist up his nose and make him feel faint. They smell increasingly delicious—tart and sweet, juicy and tender, and some of them smell like fruit but some of them smell like choice meat, and others like glazed pastries.

Soon, Harvey cannot help himself. He truly wasn’t hungry, but now his stomach twists painfully. He is frantic with craving. He plucks a bright red fruit from its branch and pops it into his mouth. He chews, and the fruit bursts; he swallows, and juice and seeds drip down his mouth. He feels, for a moment, the most satisfied he has ever felt.

Then the jungle begins to quake around him. Starting nearest him, and then spreading out in waves, the plants shrivel and blacken, and turn to dust. Harvey hurries through them, the taste of the stolen fruit turning sour on his tongue. It seems to him that the dying branches grab for his feet as he runs. He tramples piles of rotting fruit that squelch between his toes. The ground is coming apart, a sliver of earthquake trailing his steps.

He emerges on the other side of the jungle just in time. The whole thing collapses behind him, and Harvey pants to catch his breath. That’s when he sees it: The envelope, fallen open in his hand. The letter inside it is sopping wet, black with ash, and the words written on the ruined paper drip off the paper and onto the ground, where they collect in steaming black puddles. The words left on the page are gibberish. The letter is unreadable.

Harvey feels a shadow fall over his face. He looks up and sees a tall, hooded figure standing at a black crossroads in a green field. The figure holds out its hand, which looks surprisingly human.

“Are you The One Who Waits?” asks Henry.

The figure nods, and Henry shoves the letter into its hand and closes his eyes.

*

Harvey wakes back in his bedroom and promptly gets sick on the floor. Apparently, the fruit did not agree with him.

The Sandman watches him, irritated. “You ate the fruit.”

“I couldn’t help it.”

“You ruined the letter.”

Harvey turns, afraid. “You didn’t say anything about delivering the letter intact. You just said deliver the letter, and I did.”

The Sandman’s mouth grows thin. “I suppose I shall have to be more specific in the future.”

“Where was that place?”

“There are many places you can’t access but I can. That was one of them.”

“And what exactly is all this that you’re making me do?”

“Does it matter? If you want your family back, you’ll perform my tasks regardless.”

“But—”

“If I wanted to give you any more information,” says the Sandman smoothly, “I would do so. Don’t ask me pointless questions.”

He smears a fresh coat of tar across Harvey’s eyes, and Harvey falls back into his pillows for the second time.

*

Harvey is on a boat painted red and white, with silver sails that spread out like wings.

The air here is quiet and still, and the prow of the boat pushes through a thick black swamp littered with dead trees and alligator carcasses.

Harvey takes a step forward, and something crunches beneath his foot. He looks down and almost gags.

The deck of the boat is covered with the bodies of dead swans.

Find the princesses, the Sandman whispers from far away, his breath carrying the stench of the tar from his vial. One is the true princess; six are impostors. Find them and pick the right one.

Something terrible has happened here; that much is obvious to Harvey. He sees that the sky is shifting, full of malevolent clouds. He sees lightning on the horizon but hears no answering thunder. He sees thin houses built on stilts, rising up out of the water, and he calls out, hoping whoever lives there will help him find his way, but no one answers. The windows remain dark.

Harvey stands at the wheel and steers the boat for countless hours, until blisters form on his palms. It’s impossible to track the time; the light in the sky never changes. Finally, Harvey sees a black shape in the distance that looks castle-like, and princesses live in castles, so he decides to head that way.

He arrives at the gates of a castle made of stone and iron. At the gate stand seven identical figures—all in fearsome, spiked armor and voluminous cloaks. They wear helmets that resemble crowns and battle axes hang from their belts. In their hands they hold powdered cakes in the shape of pigs, offering them to Harvey for a taste.

Harvey climbs down from the boat and trudges across the barren beach to reach the princesses, for of course that’s who they are. As he walks, panic grows inside him. These princesses look exactly alike. He cannot see their faces. How is he to tell the real one from the impostors?

Harvey inspects them, licking his dry lips. He is nearly ready to give up when he notices that one of the cakes is different from the others: It is missing a bite-sized piece. It’s a risky guess, but Harvey decides that if he were surrounded by six impostors, he would want to do something to show he was the real Harvey. Perhaps, he thinks, the real princess managed to sneak a bite, and this was a sign.

There is nothing else to do. Harvey kneels in front of this princess and bows his head. “Your Highness,” he says, “you are the one true princess.”

From above and around him comes the sounds of sliding steel. He looks up in time to see the other six princesses unsheathe their axes. They let out inhuman shrieks. The true princess, the one Harvey has chosen, rips off her helmet, revealing a face so hard and beautiful that Harvey feels tears come to his eyes. She raises her axe to defend him, and Harvey turns away, shielding his face in her cloak.

*

Harvey gasps awake in his bed. His sheets are soaked with sweat and cling to him like clammy fingers.

“Well?” The Sandman sounds bored, but his eyes are alight with interest. “What happened?”

“I found her.” Harvey is still catching his breath. “At least I think so. Her cake had a bite missing from it. That’s how I knew.”

“I’m not sure what cake you’re talking about,” says the Sandman, “but I’d know if you had failed. Don’t expect me to congratulate you, though.”

Harvey frowns. His ears are still ringing with the clash of swords, and he’s more than a little annoyed. “I don’t. I expect you to release my family after I win at your stupid games.”

The Sandman looks grave, and full of secrets. “They are not games. Don’t make the mistake of treating them as such, Harvey.”

Harvey shivers without knowing why. “Fine. Can we get on with it? I’ve got four tasks to go.”

A grin spreads across the Sandman’s face, a moonbeam cutting through clouds. He seals Harvey’s eyes shut for a third time, and Harvey slips back into darkness.

*

Harvey is being thrown against walls of rock.

At least, that’s what it feels like. He breathes salt and is shaking with cold. He struggles up to breathe and is pushed back under. Something throws him into somersaults through a thick, overwhelming heaviness.

He remembers, somewhere in the back of his mind, that he is asleep, that the Sandman is waiting patiently at the foot of his bed, but that doesn’t stop Harvey from feeling like he is about to die. He needs to breathe, he needs air, he needs ground under his feet—

He wakes up on a beach awash with sunlight. A white beach littered with shells and seaweed and the corpses of sea creatures washed ashore. He is sopping wet, and struggles to lift himself up and look around. Behind him stretches a great blue sea, sparkling and calm after a night of storms. Harvey coughs up ocean water. His stomach is burning.

Find the girl disguised as a bird, whispers the Sandman, his cold, faraway fingers wiping Harvey’s wet hair back from his eyes. Set her free. Avoid the Good Doctor.

This task makes the least amount of sense yet, but Harvey forces himself across the beach and into a meadow. At first there is nothing but grass, but then ruins appear—cottages and temples, bridges and towers. They are gray and crumbling, but still beautiful. There are roads and there is a market, and people milling about. Harvey hears them chattering and feels relieved. The chattering has a friendly sound to it. Perhaps he will actually have help this time.

But when Harvey gets closer, he notices something startling about the people in this ruined village: They have beaks.

They have feathers and clawed feet. They have wings and black beady eyes. Their faces are part human; there is human flesh there, and human teeth. But the human flesh transitions into black bird feathers, and the human teeth line yellow bird beaks instead of lips. The bird-people speak in disjointed words and rattling squawks. They neither fly nor walk but instead hop around, like they don’t know what to do with themselves. They seem unnatural, cobbled together.

At the center of the town is an enormous temple with a red tiled roof. Harvey sees a figure in white standing there, surveying the domain from a terrace. Harvey ducks his head and hurries into the shadows. Could that white figure be the Good Doctor? Whoever that is.

What has happened here? Harvey can’t know for sure, but he is a smart boy and constructs a hypothesis. Perhaps the Good Doctor isn’t so good at all. Perhaps he conducts experiments, crafting birds and people into bird-people.

The air smells like medicine and burnt feathers. Harvey doesn’t like it.

He hears a ruckus and peeks around the corner of a building. A crowd of bird-people gather in a circle. There are hen-people and duck-people and a giant gobbling turkey with the face of a man and clawed fingers.

They are making fun of someone—a small bird-person whose feathers don’t look quite right.

Harvey’s skin tingles. It is the girl disguised as a bird. He must free her. Though the Good Doctor watches from on high—surely that’s him, up on that terrace—Harvey must free this girl. The bullying bird-people are kicking the girl’s legs, pecking her skin. They are jeering at her, calling her stupid, calling her beautiful in a mocking fashion.

Harvey is filled with horror and rage. This place is not right. He rushes at the girl and grabs her arm, dislodging pasted-on feathers. He runs with her toward the ocean, a mob of bird-people at their heels. The bird-people are vicious. They peck with their beaks and tear with their human teeth. They curse Harvey and the girl. They call for the Good Doctor.

Looking back over his shoulder, Harvey sees that the terrace is empty.

“Where are you taking me?” gasps the girl. Her tied-on beak has fallen. Her feathers are flying off.

Harvey doesn’t have an answer for her. His legs carry them into the ocean, and they dive. Everything in him recoils at the idea of returning to the sea that nearly drowned him, but drowning is better than becoming these things that are chasing him.

Water fills his ears. He hears a man calling out on the shore. He feels rubber gloved hands reaching for him. He loses his hold on the girl’s hand and opens his mouth to call for her, but he is lost in blackness and foam.

*

Harvey wakes shivering. He is curled into a knot on his bed, but he still feels the churning of the water and the pinch of the Good Doctor’s seeking hands.

The Sandman sits quietly beside him, inspecting him. “Well? Is she freed?”

“I don’t know.” Harvey is distraught. “I took her into the ocean. There was nowhere else to go. Those bird-people were chasing us. I panicked.”

The Sandman nods. “I think that should be fine. She is a good swimmer. And the sea holds many secrets, some of which are escape routes.”

“What is that supposed to mean?” Harvey is reaching the end of his rope, but he is only halfway finished.

The Sandman cocks his head and regards Henry. The motion is too birdlike for Harvey to feel comfortable. He turns away.

“Whatever,” he says. “Never mind. Let’s just keep going.”

“You didn’t like seeing her there, did you? Seeing her trapped and bullied?”

“Of course I didn’t! It was wrong.” Harvey’s hands clench into fists. “She didn’t deserve that. No one does.”

The Sandman nods. “I see.” He is quiet for a long time. “Well, then.” He takes out his vial, and Harvey closes his eyes. He feels the cool brush of the Sandman’s fingers, and hears him whisper, “You are halfway there, Harvey.”

*

Harvey wakes up on a bed of moss in a church graveyard.

Bells are ringing, and the church windows are full of light. Harvey sits in the damp autumn wind and waits for the Sandman’s instructions. The air smells of rain.

Marry her.

That’s all the Sandman says, and Harvey is concerned: That instruction seems particularly ominous. But he doesn’t have a choice.

Ah, but you do.

Harvey is startled to hear the Sandman speak again, and he realizes the Sandman is right. Harvey does have a choice. He doesn’t have to go through these tasks. He can return home, and leave his family to their fate.

But he can’t do that. He’s a good kid, in general. He will do the right thing.

Even with that decided, what he finds inside the church nearly sends him running. It is a congregation of people, and a priest and a bride, and an organist playing Pachelbel’s Canon in D. Typical, except for the fact that the people in this church all wear masks. The masks are shaped like mouse faces, and are plain and plastic. It might have been a funny combination, in another situation: A group of dressed-up people wearing mouse masks. But the people stand up from their pews and turn to watch Harvey as he walks down the aisle.

A great terror seizes Harvey. Now that he is closer, he can see that the masks aren’t tied on; they are sewn on. They are sewn with ugly black stitches, plastic to skin, and the skin is raw and red.

Harvey steps up beside the bride. She takes his hand, and they are wed by the priest whose voice is muffled by his mask. The final step, the priest explains, is up to Harvey. A mask sits on the altar. It is for Harvey to wear.

Harvey is sweating. He cries out for the Sandman but doesn’t hear an answer. For several long seconds, he considers running.

Then, ashamed, he takes hold of the mask and holds it before his eyes. The mask jerks into place, and a sharp pain works its way around Harvey’s face, affixing the mask to his skull. It pierces and burns. He screams and drops to his knees. His bride pats him on the shoulder, soothing him. The priest leads a hymn.

*

Harvey wakes on the floor of his bedroom, scratching at his face. The Sandman kneels beside him and catches his wild arms before he can do any more damage.

“There, there.”

Harvey pushes him away. “You didn’t say I would have to do that. You said marry her, not sew a mask to my face!”

“The masking ritual is part of marriage ceremonies there.”

“There? There where?”

The Sandman sighs. “We’ve been over this, Harvey.”

“So, I’m married to some woman who wears a mouse mask in some place I can’t access unless you send me there. What does that even mean? What will happen to her now that she’s married me?”

“Well,” the Sandman says, smiling, “that will be interesting for you to find out someday, won’t it?”

“I hate you.” Harvey climbs back into bed. He is tired and weak. “I hate you for doing this to me.”

“Everyone hates me. But sometimes these things must be done.”

Harvey lies back in bed, rigid as a board, full of anger. He refuses to acknowledge that the Sandman sounded sad, just then. He refuses to acknowledge anything but his own rage. It gives him strength.

“Twice more, Harvey,” says the Sandman, and soon Harvey’s eyes are cool with sleep.

*

Harvey is in an attic, sitting beside a dollhouse.

The attic window is dirty but ajar; a thin beam of sunlight shines on the dollhouse, illuminating its rooms, which look as though a storm has ripped through them. The doll furniture is upturned; the doll portraits have fallen from the walls.

The dolls themselves are scattered about, lying on their faces, straddling the roof, buried under sofas.

Put the dollhouse to rights, comes the Sandman’s voice, and the dolls back into their proper places.

Harvey breathes a sigh of relief. That does not sound so hard, compared to everything else, so he gets to work at once.

He takes out every doll and piece of furniture and sets them on the floor. The rooms empty, he takes a moment to inspect the dollhouse: five bedrooms, two bathrooms, a dining room, a kitchen, a parlor, a living room, a game room, an attic, a basement, a garage. Four floors altogether, counting the attic and basement.

A strange feeling comes over him as he begins putting the furniture back into place. He can’t know where the furniture is supposed to go, and yet he does. He feels it as a rightness that tugs his hands here and there—the sofa goes against the red wall in the living room; the desk goes in the green bedroom beside the fireplace.

The more furniture he replaces, the more familiar this dollhouse becomes. He feels that he has played with this dollhouse before, even though he knows that to be impossible. He feels that he has lived in this dollhouse before, which is even more impossible.

Harvey retrieves the first doll—the mother, he assumes. She has blond hair and is wearing a blue dress. He puts her in the living room, watching television. He puts the father in the kitchen, getting something to eat. He puts the brother at the top of the basement stairs.

Somehow, Harvey knows exactly where each doll should go. He matches them with their spots like magnets to magnets. He knows their names—the father, George; the mother, Pamela; the son, Herman. He knows their hopes and fears, which strikes him as odd; dolls don’t have hopes and fears.

The last doll is a small girl. Her name is Bertha, and Harvey knows she needs to go into the basement. He knows it like he knows two added to another two makes four. But when Harvey turns the tiny basement doorknob, he hears a scream.

It is the doll, Bertha. He knows it is Bertha’s scream, even though the sound is not coming from the doll; it’s coming from everywhere.

“Don’t make me go down there!” Bertha screams. She is terrified, and that makes Harvey terrified, because he can feel her fear like it’s his own. “Please, he’ll lock me in!”

He? Harvey turns to the brother doll, Herman. The markings of his face have rubbed off over time, but Harvey gets the feeling that Herman is a brute. Harvey pauses, uncertain. He knows Bertha’s place is in the basement, but he doesn’t want to put her there. But if he doesn’t put her there, he will fail in his task, and the Sandman will keep his family.

“Please, don’t do it,” sobs Bertha. She is a ghostly apparition before him, a small girl with braids and braces. “Please, don’t put me down there. He’ll lock me in, he’ll trap me. I hate being down there. It scares me!”

Harvey sees another apparition at the far end of the attic—Herman, the brother, full-sized and approaching fast.

“But you’re a doll!” Harvey protests. If they’re just dolls, it doesn’t matter where he puts them. Does it?

“Maybe to you, I’m a doll,” says Bertha, “but to me, I’m real! I wasn’t always like this! I didn’t always live here! Oh, please, please don’t do it!” Her hands are clasped, like she is praying to Harvey. He sees ghostly tears run down her cheeks.

Harvey considers it for a few more seconds. He could throw the Bertha doll into the basement and shut the tiny basement door. He could.

But he doesn’t. Bertha is too afraid, and Harvey is a good kid, in general. He grabs the Herman doll instead, and the Herman apparition, on the other side of the dollhouse, freezes.

“Put me down,” he says quietly.

Harvey stands. “No,” he says, though he is afraid, and throws the Herman doll out the attic window, into the sun.

*

Harvey awakes in his bedroom, crying. He finds the Sandman and falls to his knees.

“Please,” he chokes out, “please, don’t hurt my family. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t put the dolls back in their proper places. The girl doll, Bertha. She was scared. I couldn’t trap her in that basement. Herman was scaring her. The basement scares her. Please, please.”

The Sandman kneels and tilts up Harvey’s chin. “Ah,” he says, “but you did put the dolls in their proper places.” He wipes Harvey’s cheeks. “Some souls deserve to be thrown out, and you did that beautifully.”

Harvey sniffles, backing away. The Sandman is looking kindly at him, and somehow that’s the most disturbing thing of all. “You mean, you won’t hurt my family?”

“Not for that, no. In fact, if you had put Bertha in the basement, we would be having a very different conversation right now. You did right. But you do have one more task to complete.”

Harvey climbs back into bed. He is exhausted, but a little less so now that he has heard the Sandman’s approval. The kind words wrap around his heart, cushioning it.

“Sleep, Harvey,” whispers the Sandman. Lovingly, he seals Harvey’s eyes shut for the last time.

*

Harvey awakes in a village where it is almost midnight. In a few minutes, it will be Sunday.

The village lies nestled in a small valley between black mountains with jagged peaks, and the fields surrounding this village are on fire.

It is a cold, silver fire, so cold that it feels hot. Harvey shields his eyes from the brightness, stumbling through the door of the nearest building—a small cottage with a metal roof. He peeks out through his fingers, watching the chaos outside. Villagers run to and fro along the streets, shouting, grabbing items from their homes, abandoning their village for the hills. Harvey sees why: The silver fire is approaching the village’s outer road. Soon, it will devour every building.

“Harvey,” says a familiar voice, and Harvey turns, startled, for there, in a portrait hung on the wall, sits the Sandman in a high-backed red chair, twirling his black umbrella.

“What are you doing here? Why aren’t you talking to me in my head?”

The Sandman shrugs. “I like variation.”

“What do I have to do this time?”

The Sandman smiles, as if he appreciates how Harvey has come to accept his own mysterious ways. “The fire you see is no ordinary fire. It is star-fire. Find the fallen star and put it back in its proper place before it burns down this village.”

Harvey is aghast. “You mean, back into space?”

“Where else would a star go?”

“But that doesn’t make sense! How can I possibly do that?”

“That’s entirely up to you, Harvey.” The Sandman rises from his chair and walks out of the portrait frame without another word.

Harvey can’t waste any time. Though his mind refuses to accept what he is about to do, he rushes outside and into the wall of silver fire encroaching upon the village. It burns him; it feels like plunging into arctic waters. He can hardly open his eyes. He crawls like a blind baby on the ground, searching for the fallen star.

His hand lands upon a hard, cold stone, smooth as water. Harvey cracks open his eyes and sees a pulsing light, brighter even than the fire. It scalds his retinas, and he loses his sight. Where the star touches his palm, it brands his skin. But he holds tight to it anyway and stumbles through the village, trailing sparks behind him.

“Point me to the highest mountain,” he tells everyone he encounters, and with the villagers’ help, he finds his way to the base of a black mountain so tall that its peak seems to brush the moon.

Harvey begins to climb. He is burned and aching, and in so much pain that constant tears stream down his face. The salt inflames his wounds, but he soldiers on, because more painful than anything is the thought that if he fails, he will have failed his family.

He climbs, and he climbs. The air grows thinner, and Harvey’s breath turns to wheezing. He is cold, and he is hunted by mountain cats, but something seems to deflect them every time they pounce—maybe it’s a black umbrella being swung like an axe, or maybe it’s some kind of protective forcefield emanating from the star in Harvey’s hand. Who knows? Harvey doesn’t.

He reaches the icy slopes of the mountain peak, and can climb no farther. He looks up to the sky with eyes that can no longer see. He feels moonlight on his ruined skin. He reaches back, his brittle bones snapping, and throws the star into the sky as far as he can.

He collapses face-first into the snow.

*

Harvey is on trial.

He blinks, confused, trying to figure out why and how and where. But it’s true: He is in a courtroom, and he doesn’t recognize everyone on the jury, but he does see The One Who Waits and the one true princess, the girl disguised as a bird and his mouse-masked bride. He sees Bertha the doll, held in the lap of her girl-shaped soul.

“Sandman?” Harvey whispers, turning around and around. At least he can see now, and at least his skin is no longer burned. But he is full of fear. He has completed six tasks, but did he complete them well enough? He realizes that this is the end, that now he will learn the fate of his family.

Everyone rises when the judge enters. The judge is handsome and strong, a god among men. He wears an unfamiliar silver uniform and a black velvet cloak. The judge’s aide, a bespectacled man, rips down a curtain at the far end of the room, behind which sit Harvey’s parents and his sister, Jessie. They are sitting, but they do not see him. They do not see anything at all.

Harvey lunges for them, but he has been bound to his chair. From the bench, the judge watches coldly.

“In the case of Harvey Black,” the girl disguised as a bird reads, “the jury has reached its verdict.”

“Wait!” Harvey struggles against his bindings. “I haven’t gotten to speak! I don’t have a lawyer! Can’t I ask some of the jurors to speak for me as witnesses? I helped them, I saved them! Ask the Sandman, he’ll tell you! Where is he?”

“There will be no more interruptions,” says the judge, his voice a terrible blend of thousands. “What is the verdict?”

“According to the testimony of the Sandman,” says the girl disguised as a bird, “Harvey Black has completed his tasks in a manner satisfying their accord.”

Harvey slumps back in his chair. “So my family is safe?”

“Perhaps,” intones the judge. “You have a choice now, Harvey. You can go home and wake up, and all this will have been a mere dream—but your family may or may not return with you.”

Harvey is outraged. “What do you mean? I did exactly what I was supposed to!”

“Or,” the judge continues, talking over Harvey’s cries, “you can stay here and work for the Sandman, and your family will be returned home safely, guaranteed.”

“Where is he? Bring him here! He promised, he promised!”

Everyone watches Harvey as he cries tears of betrayal and fear, alone on his chair. He cries for a long time, but when he raises his head next, his expression is one of determination.

“Fine,” he says, his voice clogged with sadness, “I’ll stay here. Let them go. Just let them go.”

In an instant, Harvey’s parents and sister vanish, and the judge’s face melts into a warm smile. His outer skin sheds, revealing a familiar figure: the sallow, dark-eyed Sandman, leaning on his umbrella.

“You’ve done well, Harvey,” says the Sandman, as the jury applauds. The Sandman’s voice is rough, and his eyes bright. “I am proud of you. You may go.”

Flabbergasted, Harvey says, “What? What do you mean? What just happened? You said—”

“I gave you a terrible choice—save yourself or save your family, and you chose the latter. Not many would have done that, Harvey. Not many would have kept Bertha out of the basement, or sewn a mask to his own face.” The Sandman approaches, and puts a hand on each of Harvey’s shoulders. Harvey’s chains crumble, releasing him. “You are special, Harvey. I chose well, and I thank you for proving me right.”

Harvey feels a strange warmth at having made the Sandman so proud, even though this man lies at the root of his recent troubles. “You said I could go. Are you telling the truth?”

“I always tell the truth, Harvey, even when it makes people uncomfortable to hear it.”

“Who are you?”

The Sandman holds out his hands. “I am Morpheus. I am the Bringer of Dreams. I am Ole Lukøje. I am the Old Storyteller, the Dreamwalker, the Sandman. I enter worlds only accessible through dreams, where I right wrongs and put chaos into order. I guide those who die in their sleep to the Lord of the Dead. I wrangle nightmares and coax peace into troubled hearts and coax trouble into hearts of the content. I am the balance of the universe.”

The Sandman crouches. His face is kindly, and Harvey cannot look away from those deep, dark eyes. “Someday, you will replace me, Harvey. You chose it, just now. I can’t change that. But I can do this much for you: I can give you what was not given me. I can give you your life first.”

He stands, and helps Harvey to his feet. “We’ll meet again, Harvey Black, when you’re old and wrinkled, and your heart slows in your sleep. We’ll meet again, and I will teach you everything I know. Until then—” The Sandman takes out the familiar vial.

“But wait!” Harvey says, throwing out his arm. He is suddenly sad to leave. He sees entire worlds in the Sandman’s endless eyes. He sees gods and monsters, dreams and death. He sees a lonely man.

But he cannot keep his eyes open, and soon he sees nothing at all.

*

Harvey wakes up to the smell of breakfast cooking downstairs, of his family chatting about their day. It is Sunday morning, and he remembers nothing of the previous night except falling asleep. He feels well-rested, and stretches in the sunlight.

Wayward Sons and Windblown Daughters

Mr. Farringdale and Mr. Blake stood in Pemberton Street, hunched against the coal smoke and a driving green rain, peering at each other gravely.

“It was found with the gentleman?” Mr. Farringdale inquired. He was holding a small bundle of envelopes—tied with a red ribbon—and he was holding it very delicately, as if it were valuable, or a severed hand.

“It was,” said Mr. Blake. “And it is very odd. The writings, I mean. Fanciful and not particularly helpful. But perhaps they will shed some light on the matter for you. I thought you might read them and give me your opinion by tomorrow.”

Mr. Farringdale nodded and tucked the letters into his coat. Pemberton Street traffic drifted around the two men, strangely silent in the rain. Shadow-clouds rolled overhead. Behind Mr. Blake, in the police station, a grate clanged, echoing.

“I shall read them this evening,” said Mr Farringdale. “Though if they shed no light on the matter for you, I fear they will do very little for me. Good day.”

Mr. Farringdale touched his hat and hurried away up the street. The rain flew at his face, and it smelled of rust and chemicals.

* * *

Mr. Farringdale went to his lodgings in Aberlyne. His rooms were situated at the top of a steep, dim staircase in one of those old, narrow, complicated sorts of city-houses. Mr. Farringdale was only renting.

He lived in London officially, in a scrubbed brick three-story with a wife and two children. He was not there often, however. He was not here often either. He was wherever he had to be, for however long he was needed, and then he was elsewhere. His landlady did not call out to him as he climbed the stairs to his rooms.

He found the stove already lit upon undoing his door. He stamped the rain off. He filled himself a pot of tea and took off his overshoes, then his under-shoes. He hung up his coat.

The bundle of letters sat on a chair, the red ribbon glimmering softly in the stove-light.

Mr. Farringdale took his supper on a wobbly table, watching the rain dribble and worm down the windowpanes. He drank his tea.

Then he settled himself into a large threadbare chair and began to read . . .

* * *

February 15th, 1862

Dear Papa,

We are beginning to suspect we are not real people. I often feel I am made of wind and bits of ash, and that I cannot stand upright or all my bones will snap. Harry thinks he might be made from wax. He told me the other night that when he was standing too close to the candle in Mistress Hannicky’s study he thought his skin was going runny. He thought it all might drip away. Do you think we are not real people? Do you think we are changelings, perhaps?

Please write back.

It is very lonely here, and it is always raining. Harry is the only person I talk to, but he is very quiet. Some days I think Harry is lost. He tells me he is in a deep forest, even when he is directly beside me. I would call him silly, but then some days I feel as though the wind is singing to me and calling me away. What do you think, Papa? Do you ever suppose you do not belong in the place you are? Do you ever think you are not like all the people around you and that perhaps you should be somewhere else?

It is beginning to storm and thunder outside. I feel the rain all day long. Sometimes I feel like I am in the rafters, staring down at myself. I need to go before the others come in.

Do you think I might come home soon?

Your affectionate daughter,

Pellinora Quitts

P.S. Could you send me a stick of peppermint? I told the other girls you owned a factory that made peppermint sticks. They do not believe me, but perhaps if they did we would be friends. (?)

* * *

Mr. Farringdale frowned and set the letter aside. He picked up the next envelope. A reply. London address. Thick, creamy stock and monogrammed stationary. It was written very differently from the first letter. Where that one was spelled out in the jerking, uneven hand of a child, this one was all sharp points and swift lines, thin bits of ink, controlled.

* * *

March 6th, 1862

Pellinora,

I was displeased to hear that school is not to your liking. It is, however, one of the finest in the country, and very expensive, and if you are sad I think it may well be because you are not trying to be happy. Have you spoken to the other children? Perhaps if you made an effort to become acquainted with the other little girls there, things would appear brighter.

Furthermore, your gloominess is little wonder when all you do is associate with Harry Snails. He is not a good sort. His own parents say so. He is mean and petty and you will do well to remember the reasons he was sent away. You would do well to choose a better friend.

I must be going now. I have no more to write. We shall see you at Christmas, and you shall have a rocking horse.

Regards,

Your father

* * *

Mr. Farringdale read the letter again because it didn’t really seem like a reply. He wondered if perhaps the letters were out of order. But no, this was the reply, dated three weeks after the first letter from Pellinora. Mr. Farringdale took a sip of tea. He opened the next envelope and slid out its contents.

* * *

June 16th, 1862

Dear Papa,

The other children were beastly today, especially to Harry. They were throwing rocks at him. I told them not to. I told them Harry didn’t mean to be horrid. I know he can be. He can be dreadfully mean, but he has had such a hard life, what with going to India and being sick and alone for so long. I understand him, don’t you, Papa? He told the other children he didn’t want to go near the warm food or it would melt him from the inside out, and then when they didn’t believe him he began to call them names. When we were sent outside to take the air, that was when they started throwing the rocks. One cut Harry right over the eye and he bled a lot. They were throwing rocks at me, too, I don’t know why. I pulled Harry away then and we ran out onto the moor. They are very wild, these moors. Mistress Hannicky says we are never to go wandering there, but Papa, I was afraid they would hurt Harry to death! So we ran and ran over the moor. The ground is soft and strange there, Papa, like wet, mossy skin. We ran so long and then we came to the loveliest little pond, just sitting there in the middle of nowhere, lovely as you like. We couldn’t run anymore then. The other children weren’t following us and so Harry and I just sat down and cried.

The wind made me feel better after a while, but Harry is still angry.

I’m back now in school but I wish I didn’t have to be. Will you come and take me away? And Harry, too? It is so cold all the time. It is dreadfully cold, and they never build fires. The headmistress is very cruel. I don’t know why she will not build a fire.

Your affectionate daughter,

Pellinora Quitts

P.S. I think perhaps you forgot to read the post script on my last letter. Could you please send me a stick of peppermint? The other girls don’t believe me that you are rich. They think perhaps you’ve left me here, and that I’ll never leave again, but of course I’m coming home for Christmas. And Harry, too?

* * *

The next letter was from the father again. It had been sent only three days later.

* * *

October 15th, 1862

Pellinora,

You will stay at Carrybruck until the term is out. You will attend to yourself, and what happens to Harry Snail is none of your concern. I hope you are not being a trial to the other children. We will discuss your further education in December when you are home.

Regards,

You father

* * *

Cold, thought Mr. Farringdale. He sipped his tea.

* * *

October 30th, 1862

Dear Papa,

We have a friend now, Papa! Here at school! He is a bit strange and quiet, but oh! a friend! He walks and talks with us. He says he saw us out on the moor that day, crying by the pond, and he followed us back, do you believe it? I think perhaps he is from one of the farms, but he is very interesting. He knows so much. He asked us what the trouble was, why we had been crying. So nice. We told him. We told him everything and how the other children were dreadful. We told him we thought we were perhaps ashes and wax and ought to be somewhere else. Do you know what he said? He said, it is not the children who are dreadful.